Back in 2006 when I began preliminary work on THE ASWANG PHENOMENON documentary, I had 5 main questions I was trying to answer. What is an aswang? Where did the word come from? Why are there so many different types? Why are they predominantly women? Why is Capiz suspected as their home? I think I answered 3 of those questions well, 1 not so great, and I completely abandoned another. The orphaned question was “Where did the word come from?” I had always meant to answer this, and have tried over the years, but it always proved to be too ambiguous.

Before I begin, let’s talk a little bit about hypothesis, theory and fact. Many people (myself included at times) use the word ‘theory’ to mean an idea or hunch that someone has, but the word ‘theory’ better refers to the way that we interpret facts. A theory starts as a hypothesis – a supposition or proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation. In other words, a hypothesis is a suggested solution for an unexplained occurrence that may not fit into a currently accepted theory. If enough people approach the same hypothesis and come up with the same results, it moves into theory – with the facts supporting it. In linguistics, a diachronic approach considers the development and evolution of a language through history – looking at similar words, meanings, and possible migratory paths. There are many hypothesis regarding the etymology of the word ‘aswang’, but I don’t believe any have moved forward into theory until now.

What is an Aswang?

Aswang is an umbrella term for various shape-shifting evil spirits in Filipino folklore, such as vampires, ghouls, witches, viscera suckers, and werebeasts. The Aswang is the subject of a wide variety of myths, stories, arts, and films, as it is well known throughout the Philippines.

Maximo Ramos explains in THE ASWANG COMPLEX IN PHILIPPINE FOLKLORE: The aswang concept is most usefully understood as a congeries of beliefs about five types of mythical beings identifiable with certain creatures of the European tradition: (1) the blood-sucking vampire, (2) the self-segmenting viscera sucker, (3) the man-eating weredog, (4) the vindictive or evil-eye witch, and (5) the carrion-eating ghoul. Thus when Philippine folk speak of the aswang, they generally refer to the physical traits, habitat, or activities of these five types of mythical beings, and sometimes also of other mythical entities like the demon, dwarf, and elf. This transfer of traits and functions is characteristic of oral traditions, and it is the business of the student to clear up the confusion.

THE VAMPIRE

By Philippine folk traditions, the vampire is a bloodsucking creature disguised as a beautiful maiden. It marries an unsuspecting youth and thus can sip a little of his blood each night till he dies of anemia, whereupon the monster gets itself another husband. To suck blood the vampire uses the tip of its tongue, pointed like the proboscis of a mosquito, to pierce the jugular vein.

THE VISCERA SUCKER

The viscera sucker is a mythical being said to suck out the internal organs (naguneg in Iloko, laman luob in Tagalog, kasudlan in West Visayan) or to feed on the voided phlegm of the sick. This creature rarely occurs in European folklore but is widespread in Malaysia. It is reported to look like an attractive woman by day, buxom, long-haired, and light complexioned. Its tongue is extended, narrow, and tubular like a drinking straw — but not pointed like the vampire’s— and it is capable of being distended to a great length. At night the monster discards its lower body from the waist down and flies or floats or glides out.

THE WEREDOG

The weredog is a mythical being said to be a man or woman— chiefly the former—by day, but at night to turn into a ferocious beast, principally a dog, known as aso in many Philippine languages.A werewolf is identified with the fiercest animal in a region, so that Europe has werewolves, China werefoxes, and India weretigers. Since there are no wolves in the Philippines, the term weredog is more appropriate; although the term werebeast may, in some cases, be even more applicable.

THE WITCHES

Another member of the cluster of mythical concepts encompassed by the term aswang is the witch, believed by the folk to be a man or woman—mostly the latter— who is extremely vindictive or who causes sickness without meaning to do so. By magically intruding various objects—shells, bone, unhusked rice, fish, and insects of various species—through the victim’s bodily orifices or by herself entering the victim’s body, the Philippine witch punishes those by whom she has been put out. Or by an innocent look or remark, she also makes an equally innocent victim ill. Unlike the European witches, however, the Philippine witch has no appetite for human flesh. She is shy and lives in abandoned houses at the outskirts of towns and villages. She will not look people straight in the eye because the image in the pupils of her eyes is said to be upside down and the pupils are thin and elongated like a cat’s or lizard’s in bright sunshine.

THE GHOUL

The Philippine ghoul is said to steal human corpses and devour them. For this purpose, its nails are horny, curved, and sharp and its teeth pointed. Its smell and breath are fetid, and though generally invisible, the creature is said to look like a human being when it shows itself.

ASU-ASUAN / ÁSO

Maximo Ramos has done more work and research on the subject of Philippine folkloric spirits and beings than anyone else. When he hypothesized a possible origin of the word aswang as being “perhaps a shortened form of asu-asuan (“the likeness of a dog”)”, I took time to look into it. The werebeast classification of aswang is such a small part of the folk beliefs that I really had a difficult time accepting that this telescoped term was the origin. When examining the available historical documentation of the Philippines, it was extremely challenging to find any snippets to back it up. While I respect everything that Ramos has contributed to the study of Philippine myth and folklore, I do often find myself disagreeing with his conjecture. However, he may not be entirely incorrect.

This hypothesis is somewhat supported in Francis X. Lynch’s paper AN MGA ASUWANG: A BICOL BELIEF, where he wrote:

The origin of the term is less clear, though it is probably derived from the word áso, meaning dog. Since the Bicol word for dog is not áso but ayám, there is an indication that the term was borrowed or introduced from another region, a point which is outside the scope of the present descriptive paper.

Two name-origin theories, offered by informants living in widely separated towns, are worthy of mention here. A man of Magarao, Camarines Sur, tells us that the word asuwáng is derived from “… kaguwáng, an animal of the fox type which has as its food fowls and other smaller animals.” Another informant, from a barrio of Aroroy on the island of Masbate, claims that “Asuwáng is derived from ashô. This is a kind of animal whose physical structure resembles that of the bear, for it has a long and protruding mouth which is provided with sharp canine teeth to enable it to suck the blood of its prey.” It is noteworthy that neither informant refers the term to the word áso, but both make reference to a carnivorous, long-snouted mammal.

It is unclear if Ramos came up with his hypothesis independently of Lynch, or if it was directly influenced. Ramos references Lynch’s work in his first dissertation, THE CREATURES OF PHILIPPINE LOWER MYTHOLOGY.

Something we have learned since the mid-twentieth century is that we must go beyond the Philippine borders when trying to understand the origins of myth and folklore. If we lock ourselves in the Philippines, the trend becomes a quest for confirming evidence while ignoring disconfirming cases. This is how we end up with absurd hypothesis such as the Spanish inventing the aswang out of desire to depower the Babaylan and freedom fighters – which is false. The Spanish certainly put local shamans in league with the devil, but may not have entirely misrepresented the aswang in their documentation. The confusion comes when the classification used for both shamans and aswang (among others) in the Spanish documents translates as “witch”.

One of the things I love about operating THE ASWANG PROJECT is that I get access to thousands of people who give feedback, advice and assistance. The day I published this article, Gelo Uygongco commented “In the comic Tabi Po, it is said that the term comes from a shortened “asung buang” which roughly means “crazy dog”. I don’t know how much truth it holds though.” I don’t think there is any truth to it, but TABI-PO Komiks is such a staple in aswang pop culture that I wanted to include this clever hypothesis in the discussion.

Historical Mentions of the Aswang

So what do the historical documents say about the aswang? Well, most traditional beliefs were seen as ridiculous superstitions by the first Spanish colonizers. This is presented more clearly in the following excerpt from Miguel Lopez de Legazpi in 1565.

“They easily believe what is told and presented forcibly to them. They hold some superstitions, such as the casting of lots before doing anything, and other wretched practices–all of which will be easily eradicated, if we have some priests who know their language, and will preach to them.”

The first mention of the aswang was in an excerpt from: CUSTOMS OF THE TAGALOGS by Juan de Plasencia, O.S.F.

“The distinctions made among the priests of the devil were as follows:

…the eighth they called OSUANG, which is equivalent to ” sorcerer;” they say that they have seen him fly, and that he murdered men and ate their flesh. This was among the Visayas Islands; among the Tagalogs these did not exist.”

In BARANGAY: SIXTEENTH-CENTURY PHILIPPINE CULTURE AND SOCIETY, William Henry Scott summarizes: Visayans believed in a demimonde of monsters and ghouls who had the characteristics modern medicine assigns to germs—invisible, ubiquitous, harmful, avoidable by simple health precautions and home remedies, but requiring professional diagnosis, prescription, and treatment in the event of serious infections. Twentieth-century folklore considers them invisible creatures who sometimes permit themselves to be seen in their true shape or in the form of human beings, but sixteenth-century Spaniards thought they were really human beings who could assume such monstrous forms, witches whose abnormal behavior and powers were the result of demon possession or pacts with the devil. But in either case, if Visayans became convinced that a death had been caused by one of their townmates who was such a creature, he or she was put to death—along with their whole families if the victim had been a datu.

The most common but most feared were the aswang, flesh eaters who devoured the liver like a slow cancer. At the least liverish symptom, people said, “Kinibtan ang atay [Liver’s being chipped away],” and conducted a tingalok omen-seeking rite to discover the progress of the disease. If it appeared that the organ was completely consumed, emergency appeal had to be made promptly to some diwata to restore it. Aswang also ate the flesh of corpses, disinterring them if not well guarded, or actually causing them to disappear in the plain sight of mourners at a wake. Their presence was often revealed by level spots of ground they had trampled down during their witches’ dance at night, or their singing, which sounded like the cackling of a hen—nangangakak. But like all other evil creatures, they were afraid of noise and so could be kept at bay by pounding on bamboo-slat floors.

Spanish lexicons listed alok, balbal, kakag, oko, onglo, and wakwak as synonyms of aswang, but tiktik as one that flew around at night, and tanggal one that left the lower half of the body behind, or even the whole body with only the head flying off by itself.

The phenomenon of the aswang shape-shifting into a dog seems to stem from SUPERSTITIONS AND BELIEFS OF THE FILIPINOS documented by Tomás Ortiz, O.S.A.; ca., 1731. [From his PRACTICA DEL MINISTERIO (MS.)]

Among other things they also attribute to the patianac the death of children, as well as to the usang. They refer to them in the following manner. They assert that the bird called tictic is the pander of the sorcerer called usang. Flying ahead of that being, the bird shows it the houses where infants are to be born. That being takes its position on the roof of the neighboring house and thence extends its tongue in the form of a thread, which it inserts through the anus of the child and by that means sucks out its entrails and kills it. Sometimes they say that it appears in the form of a dog, sometimes of a cat, sometimes of the cockroach which crawls under the mat, and there accomplishes the abovesaid. In order to avoid that harm they do certain of the above things. To the patianac travelers also attribute their straying from or losing their road. In order to keep the right path, they undress and expose their privies to the air, and by that observance they say that they make sure of the right road; for then the patianac is afraid of them and cannot lead them astray.

Ortiz’s documentation was enforced in DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS by Fernando Blumentritt and seems to support the Ramos hypothesis of asu-asuan.

In INFORME SOBRE EL ESTADO DE LAS FILIPINAS (1842), Don Sinibaldo de Mas writes: “The superstitions of these people can be divided into three classes. The first consists in believing that certain monsters or ghosts exist, to which they give names and assign special duties, and even certain exterior forms, which are described by those who affirm that they have seen them. Such are the Tigbalan, Osuang, Patianac, Sava, Naanayo, Tavac, Nono, Mancuculan, Aiasip, the rock Mutya, etc.

I find the next excerpt from Mas particularly interesting because I have also encountered this exact same phenomenon.

“Many Spaniards, especially the curas (priests?), imagine that these beliefs are not very deeply rooted, or that they have declined, and that most of the Filipinos are free from them. This is because in the presence of such the Filipinos do not dare tell the truth, not even in the confessional, because of their fear of the reprimand that surely awaits them. I have talked to many about these things, some of whom at the beginning began to laugh, and to joke about the poor fools who put faith in such nonsense. But when they saw that I was treating the matter seriously, and with the spirit of inquiry as a real thing, they changed their tone, and made no difficulty in assuring me of the existence of the fabulous beings described above….”

When we take a step back from the Spanish lens and assume that there was belief in a being(s) causing sickness and disease, miscarriages, and often presented itself in the form of a human, we can conduct studies in other ways. In linguistics, word formation is the creation of a new word. A blend is a word formed by joining parts of two words after clipping.

ASIN + BAWANG

A portmanteau is a word that is formed by blending two different terms to create a new entity. Through blending the sounds and meanings of two existing words, a portmanteau creates a new expression that is a linguistic blend of the two individual terms. Examples would be breakfast + lunch = brunch, or cybernetic+ organism = cyborg. On November 22, 2008 Samuel Miguel Briones submitted an opinion piece titled ‘ASWANG’ A FORM OF SOCIAL CONTROL to the Philippine Daily Inquirer. Part of it reads:

“This is a reaction to the article titled, “Canadian searches for origins of ‘aswang’” by Felino V. Celino. (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 11/1/08) I understand filmmaker Jordan Clark is in the country (in Capiz province, specifically) to do more research on the “aswang presence” in Philippine culture and psyche. The term “aswang” comes from “asin” (which means salt in English) and “bawang” (which means garlic in English). These kitchen items, which are believed to ward off the “aswang,” are placed on doors, windows and beams of houses. Thus, “aswang” is a Tagalog term. In the Visayas the term for garlic is “ajos.” This was the subject matter of my undergraduate term paper for my anthropology major at Silliman University in Dumaguete City. In our curriculum—folklore, magic and religion, culture and personality—the mention of “aswang” cannot be avoided. Early cultural studies in the Philippines were done in the 1950s and ’60s. The studies covered the central plains of agricultural Luzon where most of our value systems and the Tagalog terms, such as “utang-na-loob,” “hiya,” “pakikisama,” “bayanihan,” spring from. Include “aswang,” “kapre,” “tiyanak,” “nuno sa punso” on the list.”

At the time, it was the best I could find. I didn’t quite believe it but, when researching Ramos’ asu-asuan, I did find that the Philippines has a fondness of portmanteau words. The Aspin (Asong Pinoy) is a modern name for the indigenous dogs of the Philippines. By the 20th century, dogs were called “askal“, a Tagalog-derived portmanteau of asong kalye or “street dog”. Realizing I was going to be sent down a very time consuming path, I brushed off the question in the documentary film, but I didn’t forget that this was a topic I wanted to revisit in the future.

Since revisiting this, I have found some who have quoted Briones, but have not found anyone else who have supported this hypothesis.

ASURAS (Sanskrit: असुर)

Somewhere on Wikipedia it mentions ”Aswang or “asuwang” is derived from the Sanskrit word Asura which means ‘demon’.” This is likely the most popular belief at this moment in time. However, I don’t believe it is true. I can certainly understand why one would believe it makes sense since we have other very clear examples where Sanskrit words show this pattern. Deva is the Hindu term for deity; however, devata (Devanagari: देवता; Khmer: ទេវតា (tevoda); Javanese, Balinese, Sundanese, Malay: dewata; Batak languages: debata (Toba), dibata (Karo), naibata (Simalungun); Philippine languages: diwata is a smaller, more focused deva. We can see a clear path to the Philippines.

The asura notion was first presented by Isabelo de los Reyes when speaking about the Ilocos in his 1909 LA RELIGIÓN ANTIGUA DE LOS FILIPINOS. “They had good Anitos and protectors that were the souls of the ancestors; and the souls of those who were bad in life, or were personal enemies or enemies of tribe, they were still evil or enemy, doing harm; they became their demons, which they called dákes (evil) or sairo (perverse), like the asura, Sanskrit, which means the same thing.” De los Reyes addresses the concept of demons as possibly being influenced by ‘asura’, but despite speaking about the aswang several times in this book, does not associate the term. It has been suggested to me that de los Reyes may have made the association between aswang and asura in a different paper, but I have not come across it.

The asura hypothesis is loosely enforced in the 1913 study of the Bagobo by Laura Benedict Watson where she mentions, “The traditional concept of Buso among the Bagobo has essentially the same content as that of Asuang with Visayan peoples. Both Buso and Asuang suggest the Rakshasa of Indian myth.”

Rakshasas were believed to have been created from the breath of Brahma when he was asleep at the end of the Satya Yuga. As soon as they were created, they were so filled with bloodlust that they started eating Brahma himself. Brahma shouted “Rakshama!” (Sanskrit for “Protect me!”) and Vishnu came to his aid, banishing to Earth all Rakshasas (named after Brahma’s cry for help). This creation story has been echoed in Christianized versions from the Philippines which explain the existence of “engkanto”.

While the terms Asura and Rakshasa are sometimes used interchangeably, they are different. Rakshasas were one of the class of beings created by Brahma when he created night. [incidentally, the other beings were Yakshas. Devas were created with daytime. Asuras were one of the class of deities competing for power with the Devas. The name of Asuras became associated with negative attributes in the later mythology.

Dr. Pardo de Tavera (1857-1925), a Filipino physician, historian and politician, concluded about the Indian influence in the Philippines, “The words which Tagálog borrowed, are those which signify intellectual acts, moral conceptions, emotions, superstitions, names of deities, of planets, of numerals of high number, of botany, of war and its results and consequences, and finally of titles and dignities, some animals, instruments of industry, and the names of money.”

Dr. Pardo de Taverna further argues that for a period in the early history of the Filipinos, not merely of commercial intercourse (like that of the Chinese), there was Hindu political and social domination. “I do not believe,” he says, “and I base my opinion on the same words that I have brought together in this vocabulary, that the Hindus were here simply as merchants, but that they dominated different parts of the archipelago, where to-day are spoken the most cultured languages,–the Tagálog, the Visayan, the Pampanga, and the Ilocano; and that the higher culture of these languages comes precisely from the influence of the Hindu race over the Filipino.”

Some of the more obvious influences on Philippine beliefs – besides the Datu (Village Leader) calling themselves Rajah, or Sultan, were as follows:

- Bathala or Batala (supreme being among the Tagalogs) was apparently derived from Sanskrit “bhattara” (noble lord) which appeared as the sixteenth-century title “batara” in the southern Philippines and Borneo.

- diwata (derived from Sanskrit devata देवता) is a type of deity or spirit. The term “diwata” has taken on various levels of meaning since its assimilation into the mythology of the pre-colonial Filipinos. It has its origin in the Devata beings from Hinduism and Buddhism.

- The Naga – In the Philippines it is a wingless type of dragon. The name is taken from the mythical semidivine half serpent beings in Hindu and Buddhist beliefs.

- Many fables and stories in Filipino Culture are linked to Indian arts, such as the story of monkey and the turtle, the race between deer and snail (slow and steady wins the race), and the hawk and the hen. Similarly, the major epics and folk literature of Philippines show common themes, plots, climax and ideas expressed in the Mahabharata and the Ramayana.

I’m not sure if there is enough evidence to support Pardo de Taverna’s hypothesis, but we undoubtedly see borrowed words, epics, folktales, and beliefs that can be traced along with the spread of Hinduism from India. The Indian influence is a fact, but how it spread to all areas in the Philippines is a matter of hypothesis. However, the mythical beings of Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia that are believed to be a melding of Hinduism and animist beliefs are certainly worth a further look. These would include a myriad of folkloric beings that have already been mentioned by others in comparative studies, but include the likes of the Penanggal (another type of female vampire attracted to the blood of newborn infants, which appears as the head of a woman from which her entrails trail, used to grasp her victim), Pontianak (the ghost of a stillborn female), Bajang (a kind of familiar spirit acquired by a male who says the proper incantations over the newly buried body of a stillborn child. It takes the form of a civet or musang and may cause convulsions, unconsciousness or delirium. It is considered particularly dangerous to infants and young children. In former times, some children would be given “bajang bracelets” (gelang bajang) made of black silk to protect them against it, and sharp metal objects such as scissors would be placed near babies for the same purpose. Even the striations of pregnancy are somewhat jokingly said to be the scars left by a bajang’s attack.)

Still, I am left looking for the “smoking gun” or a cognate term – a word in one language that has the same origin as a word in another language.

SUWANG

According to W. R. van Hoëvell in TANIMBAR EN TIMOR LAOET-EILANDEN: DI TIJDSCHRIFT BATAVIAN GENOOTSCHAP (1889) “Suanggi is an evil spirit in the shape of a person having magical power to cause disease and illness.” This caught my interest back in 2011 during the final edits of The Aswang Phenomenon and I was still attempting to find the origins of the term aswang. While I could certainly draw parallels and the language group fit, I eventually abandoned it when a few hours of research turned into a few days and the release date of the film approached.

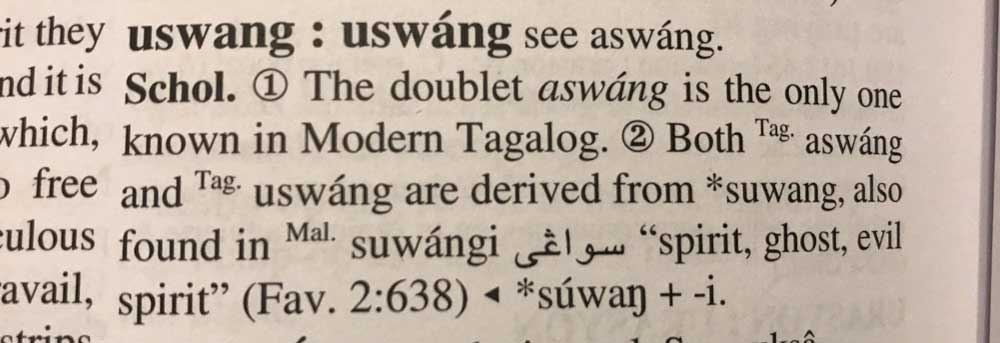

Jump ahead to July 2019. I was reading various parts of Jean-Paul G. Potet’s extremely comprehensive ANCIENT BELIEFS OF THE TAGALOGS, and I found the following entry. “Both aswáng and uswang are derived from *suwang, also found in (Mal.) Suwángi (spirit, Ghost, evil spirit” (Fav. 2:638), referring to Pierre Favre’s 1880 DICTIONNAIRE FRANÇAIS-MALAIS.

The Malay term suwāng translates to “twilight” in English. (ENGLISH-SULU-MALAY VOCABULARY: WITH USEFUL SENTENCES, TABLES, AND C, Andson Cowie, 1893).

In the OCEANIC LINGUISTICS, VOL. 49, NO. 2 paper, Manide: An Undescribed Philippine Language by Jason William Lobel, Manide is explained to be a language spoken by a population of about 4,000 indigenous Negrito Filipinos living in and around the province of Camarines Norte in the southern part of the large northern Philippine island of Luzon. Approximately 28.5 percent of the nearly 1,000 lexical items appear to be unique, either new coinages or forms that underwent phonological or semantic shifts. The following example is given under “phonological shifts”: ghost – suwáng /suwáŋ/ (cf. Tagalog aswang). Whether this provides evidence that aswang was created from suwáng or vice versa could potentially be argued either way.

I decided to dig deeper into this particular topic again. Sorting through boxes, I gathered my old notes to compose this article. I then branched out for other resources that may not have been available in 2011. This is when I came across the 2014 book THE EMPTY SEASHELL: WITCHCRAFT AND DOUBT ON AN INDONESIAN ISLAND by Nils Bubandt which “explores what it is like to live in a world where cannibal witches are undeniably real, yet too ephemeral and contradictory to be an object of belief”. I immediately bought the Kobo version and read it.

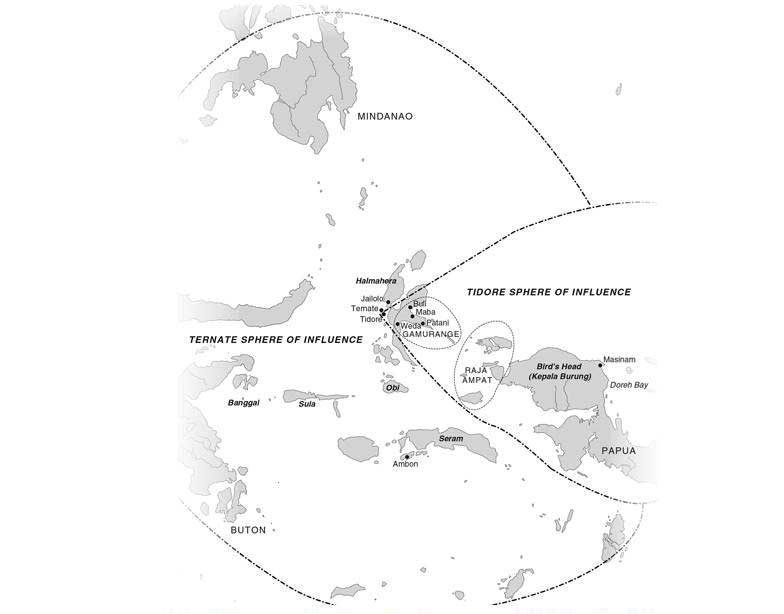

In it Bubandt has cataloged: “The suanggi—variously conceived and referred to as suangi, suwangi, swangi, or suaki—is also known and feared in many other parts of eastern Indonesia along an arc that stretches from the islands of Sumba, Flores, Roti, and Timor, across North Sulawesi, Maluku , and North Maluku, to the Bird’s Head area in Papua in the east. A similar being that is able to turn into an animal, and waylays people at night to kill them and feed off their corpses, is known by the cognate term aswang in the Philippines.

The etymology of the term suanggi is unclear. As one of the only sources, Wilken ventures the conjecture that it is derived from wangi or wengi in Javanese, and bangi in Makassarese, all of which he translates as “night” or “at night” (1912:36). It is striking, however, that the term suanggi is almost exclusive to areas within the historical sphere of influence of the North Malukan sultanates of Ternate and Tidore (to which both Papua and the southern Philippines also belonged), where the term is documented in the earliest period of contact with European colonizers in the sixteenth century . An example of the long archival trace of the suanggi in the colonial records is provided by the scribe of Antonio de Brito, the first Portuguese governor on Ternate (1522–25), who notes how the Ternate-Portuguese army was aided in one of its frequent bloody skirmishes with Tidore by inhabitants from Gam Konora on north Halmahera. Among these inhabitants were many who were known as “suanggi men” because of their ability to make themselves invisible.

The semantic variations of the suanggi, for one, were simply too great, in some places being a sorcerer who learns technique, in other places a cannibal witch. Equally important, however, to the failed comparative ambition were its theoretical bearings. The part-whole relationship between social structure and evil figure postulated simply did not hold. I suggest it is time to reassess the complexity of the suangi complex in particular (and of witchcraft in general) by releasing it from the social part-whole relationship within which it has been trapped. Hopefully, what I have to say about the corporeality, inaccessibility, and doubt associated with witchcraft in Buli may find some comparative purchase not only in the eastern part of the Indian Ocean but also beyond.”

When comparing it to aspects of the aswang, it certainly has.

Again, the day I published this article, Karl Gaverza (SPIRITS OF THE PHILIPPINE ARCHIPELAGO) messaged to re-enforce this hypothesis by pointing out Michael Tan had mentioned something similar in his 2008 book REVISITING USOG, PASMA, KULAM: “Linguistically, the term aswang is probably closely related to the keswange belief complex in the Moluccan archipelago, the suangi being ‘a witch born with malevolent powers.'” The source referenced by Tan was written by Koentjaraningrat in ETHNIC GROUPS OF INSULAR SOUTHEAST ASIA, VOL. 1: INDONESIA, ANDAMAN ISLANDS & MADAGASCAR (1972) where keswange (witchcraft) is discussed.

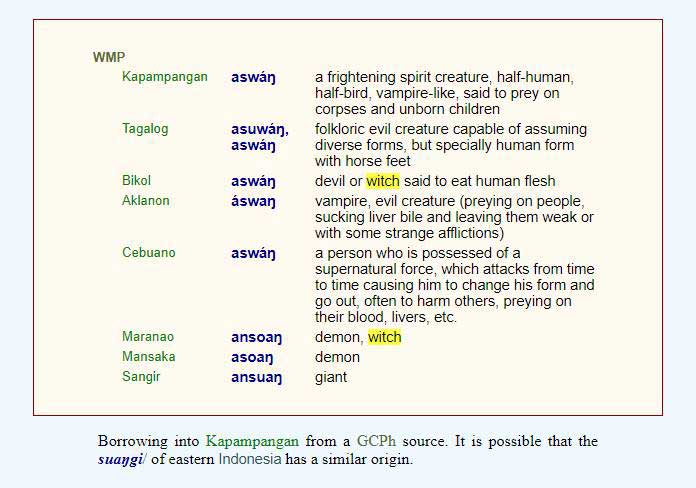

Karl went further to support this hypothesis by providing an entry in the AUSTRONESIAN COMPARATIVE DICTIONARY, displaying various regional incarnations of the aswang term. It contains the footnote “Borrowing into Kapampangan from a GCPh source (Greater Central Philippine languages are a proposed subgroup of the Austronesian language family). It is possible that the suaŋgi/ of eastern Indonesia has a similar origin.”

CONCLUSION

While I never did find my “smoking gun”, I have become satisfied that the term aswang comes from the word suwang/ suanggi. The reason this hasn’t been presented before is that there simply weren’t enough independent studies being made to support it – or at least there wasn’t a compilation of them presented as I have done here. Although the origin of suwang is unknown, the Malay language was the ‘lingua franca’ of the Philippine archipelago prior to Spanish rule which could have contributed to it. Or it may stem from an older Austronesian root word that has not yet been properly cataloged. Which way this influence went is a matter for further debate, but I feel there is (at the very least) enough evidence to debunk all the other hypothesis. Current available documentation shows the cognates aswang and suanggi both share a similar ambiguity and amorphous nature to describe a myriad of folkoric beings, witchcraft, events, and happenings. They have both been recorded historically as long as records have existed in the region, and still hold influence over the regions they are thought to inhabit. The maps above show a correlating sphere of influence that makes it possible for the term to have made its travels. While some of the other hypothesis for the aswang may hold some influence over how it was historically documented, none have been corroborated as well as suwang, which is why I feel confident suggesting this hypothesis move forward as a theory.

Unless someone has a better hunch?

SOURCES:

Wilken, G. A. 1912. Verspreide Geschriften: Geschriften over Animisme en daarmede verband houdende Geloofsuitingen. Deel III. The Hague: van Dorph and Co.

The Aswang Complex in Philippine Folklore, Maximo Ramos, Phoenix Publishing 1990

The Creature of Philippine Lower Mythology, Maximo Ramos, Phoenix Publishing 1990

An Mga Asuwang: A Bicol Belief, Francis X. Lynch, S.J., The Philippine Social Sciences and Humanities Review Vol. XIV, No. 4, December 1949

Barangay, William Henry Scott, Ateneo Press, 1994

Ancient Beliefs and Customs of the Tagalogs, Jean-Paul G. Potet, Lulu Press, Inc., 2017

The Empty Seashell: Witchcraft and Doubt on an Indonesian Island, Nils Bubandt, Cornell University Press, 2014

Tanimbar en Timor Laoet-Eilanden: di Tijdschrift Batavian Genootschap , W. R. van Hoëvell, 1889

The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803, Blair and Robertson

LA RELIGIÓN ANTIGUA DE LOS FILIPINOS, Isabelo de los Reyes, 1909

Bagobo Myths, Benedict, Laura Watson, The Journal of American Folklore, 1913

Revisting Usog, Pasma, Kulam, Michael Tan, The University of the Philippines Press, 2008

Austronesian Comparative Dictionary http://www.trussel2.com

English-Sulu-Malay Vocabulary: With Useful Sentences, Tables, andc, Andson Cowie, 1893

OCEANIC LINGUISTICS, VOL. 49, NO. 2 , Manide: An Undescribed Philippine Language, Jason William Lobel, UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA, 2010

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.