On the island of Panay in the Visayas, women in pre-colonial times were held in high regard for their wisdom and judgment. Their status can be seen in a legend about Lubluban, the first Visayan lawgiver.

The following are excerpts from Miguel de Loarca’s Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas.

During their revelries, the singers who have good voices recite the exploits of olden times; thus they always possess a knowledge of past events. The people of the coast, who are called the Yligueynes, believe that heaven and earth had no beginning, and that there were two gods, one called Captan and the other Maguayen. They believe that the land breeze and the sea breeze were married; and that the land breeze brought forth a reed, which was planted by the god Captan. When the reed grew, it broke into two sections, which became a man and a woman. To the man they gave the name of Sicalac, and that is the reason why men from that time on have been called lalac; the woman they called Sicavay, and thenceforth women have been called babayes.

One day the man asked the woman to marry him, for there were no other people in the world; but she refused, saying that they were brother and sister, born of the same reed, with only one knot between them; and that she would not marry him, since he was her brother. Finally they agreed to ask advice from the tunnies of the sea, and from the doves of the air; they also went to the earthquake, who said that it was necessary for them to marry, so that the world might be peopled. They married, and called their first son Sibo; then a daughter was born to them, and they gave her the name of Samar. This brother and sister also had a daughter, called Lubluban. She married Pandaguan, a son of the first pair, and had a son called Anoranor. Pandaguan was the first to invent a net for fishing at sea; and, the first time when he used it, he caught a shark and brought it on shore, thinking that it would not die. But the shark died when brought ashore; and Pandaguan, when he saw this, began to mourn and weep over it—complaining against the gods for having allowed the shark to die, when no one had died before that time. It is said that the god Captan, on hearing this, sent the flies to ascertain who the dead one was; but, as the flies did not dare to go, Captan sent the weevil, who brought back the news of the shark’s death. The god Captan was displeased at these obsequies to a fish. He and Maguayen made a thunderbolt, with which they killed Pandaguan; he remained thirty days in the infernal regions, at the end of which time the gods took pity upon him, brought him back to life, and returned him to the world. While Pandaguan was dead, his wife Lubluban became the concubine of a man called Maracoyrun; and these people say that at that time concubinage began in the world. When Pandaguan returned, he did not find his wife at home, because she had been invited by her friend to feast upon a pig that he had stolen; and the natives say that this was the first theft committed in the world. Pandaguan sent his son for Lubluban, but she refused to go home, saying that the dead do not return to the world. At this answer Pandaguan became angry, and returned to the infernal regions. The people believe that, if his wife had obeyed his summons, and he had not gone back at that time, all the dead would return to life.

THE LAWS & RULES OF LUBLUBAN

One of the observances which is carried out with most rigor is that called larao. This rule requires that when a chief dies all must mourn him, and must observe the following restrictions: No one shall quarrel with any other during the time of mourning, and especially at the time of the burial. Spears must be carried point downward, and daggers be carried in the belt with hilt reversed. No gala or colored dress shall be worn during that time. There must be no singing on board a barangay when returning to the village, but strict silence is maintained. They make an enclosure around the house of the dead man; and if anyone, great or small, passes by and transgresses this bound, he shall be punished. In order that all men may know of a chief’s death and no one feign ignorance, one of the timaguas who is held in honor goes through the village and makes announcement of the mourning. He who transgresses the law must pay the penalty, without fail. If he who does this wrong be a slave—one of those who serve without the dwelling—and has not the means to pay, his owner pays for him; but the latter takes the slave to his own house, that he may serve him, and makes him an ayoey. They say that these rules were left to them by Lubluban and Panas. To some, especially to the religious, it has seemed as if they were too rigorous for these people; but they were general among chiefs, timaguas, and slaves.

Wars. The first man who waged war, according to their story, was Panas, the son of that Anoranor, who was grandson of the first human [parents: crossed out in MS.] beings. He declared war against Mañgaran, on account of an inheritance; and from that time date the first wars, because the people were divided into two factions, and hostility was handed down from father to son. They say that Panas was the first man to use weapons in fighting.

Just wars. There are three cases in which these natives regard war as just. The first is when an Indian goes to another village and is there put to death without cause; the second, when their wives are stolen from them; and the third is when they go in friendly manner to trade at any village, and there, under the appearance of friendship, are wronged or maltreated.

Laws. They say that the laws by which they have thus far been governed were left to them by Lubluban, the woman whom we have already mentioned. Of these laws only the chiefs are defenders and executors There are no judges, although there are mediators who go from one party to another to bring about a reconciliation.

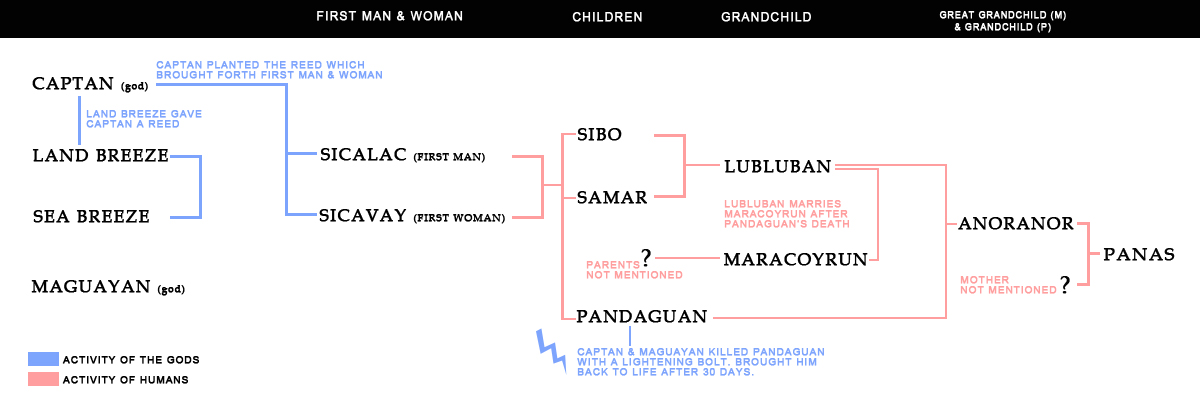

VISUALIZING LUBLUBAN’S LINEAGE

Perhaps I am easily confused, but I had a few “huh?” moments the first time I read through this document. Those who have been following The Aswang Project for long enough know that I love to create charts for myself. I wanted to clear up the following: ” Panas, the son of that Anoranor, who was grandson of the first human.” Anoranor was the grandson from the paternal side, but was the great grandson on the maternal side, since Lubluban married her uncle, Pandaguan. I was also hoping I could visualize who Maracoyrun’s parents were and who was the mother of Panas. Maracoyrun is likely another child from Sicalac and Sicavay. I could also guess that there were likely more children from the first man and woman as their marriage was sanctioned for the purpose of peopling the world. The mother of Panas would likely be a child or grandchild from these unmentioned children. It is not uncommon for only the names of culture bringers or heroes being remembered in epics and myth.

As always, I welcome comments and feedback over at THE ASWANG PROJECT Facebook and Instagram pages.

SOURCE: Miguel de Loarca, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas, Arevalo, June, 1582

ALSO READ: Examining The ‘First Man & Woman From Bamboo’ Philippine Myths

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.