Every country has a long, rich tradition of invoking supernatural threats in order to keep children in line and on curfew. Parents have an arsenal of tactics they use to get their children to obey, but when those fail there is another supernatural being who might be able to help. It has many names and takes on different forms throughout the world, but every culture on Earth knows him: the shadowy being who feeds on a diet of naughty children. To the kids, it is evil, and they take no delight in its uneasy alliance with desperate parents. We know it as the boogeyman, but in the Philippines, it goes by the term “Mumu“. The mere uttering of the name sends some children into a frenzy, whether being asked to arrive home before dark, take a nap, or go to bed so parents can have their ‘grown-up time’. Fear is an excellent motivator.

The Mumu is particularly interesting to me because I spent the better part of 10 years researching Philippine mythology and folklore and never came across the term. It isn’t in the books I read, it wasn’t talked about by my interviewees, and there is almost no information about it online. There are several reasons for this, but it essentially boils down to the point that the Mumu is not in the traditional realm of myth, legends or folklore, but is instead more of a supernatural character – meaning it is believed by some people to exist, even though it is impossible according to known scientific laws. It also doesn’t really adhere to any moral lessons of traditional folk tales. This doesn’t mean that there is no social function to the Mumu, simply that the lesson does not come from the story itself. We will talk more about this later.

I was introduced to the term while speaking with a Canadian friend of mine about the aswang. He told me that his wife from Ilocos doesn’t believe in the aswang, but is terrified of the “mumu”. The Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon is where one (me) stumbles upon some obscure piece of information—often an unfamiliar word or name—and soon afterwards encounters the same subject again, often repeatedly. This is exactly what happened to me with the Mumu. On my subsequent trips to the Philippines, regardless of region, I would hear parents joking about it, children teasing each other when one went into a darkened room, and saw it pasted along the spines of the massively popular ‘true ghost story’ pocket books.

What is a Mumu?

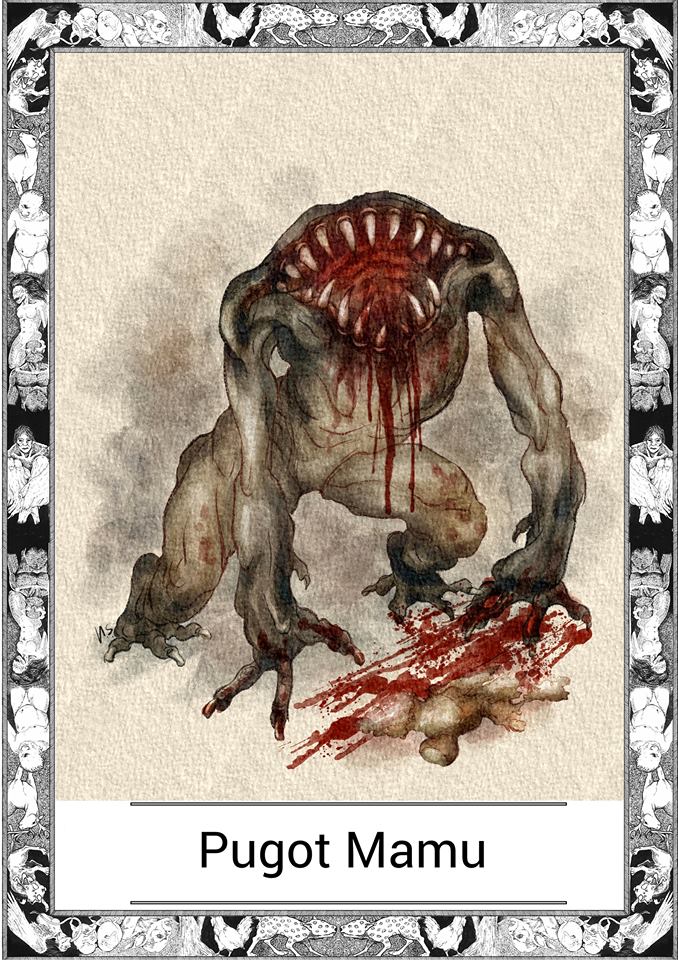

In its simplest form, the Mumu is a malevolent spirit that lurks in darkened, shadowy corners waiting to snatch children away from their families. However, I posed this question to our amazing group over at the The Aswang Project Facebook Page and found that the definition changes from region to region. In the National Capital Region (Metro Manila), the most common belief is that the Mumu is a ghost or spirit that has unfinished business in our world, has not been given last rites, or have not yet accepted their death. As we move northward on Luzon the belief changes into a spirit that feeds on children or takes their soul. In Pamapanga, it is known as the Pugot-Mamu – a horrific headless being that swallows children through its serrated neck.

When we move south through the Philippines towards Bicol and the Eastern Visayas, the term Mumu is used to describe a variety of mythical beings and ‘engkanto’. The same can be said for Negros and Mindanao. In Iloilo, however, the Mumu is likened to the Tamawo – beautiful, tiny beings that steal infants from people’s yards. They offer black rice and yellow root to children. If they accept, they will never be seen again. These modern beliefs in the Mumu may be due to much older animist beliefs in spirits. In the pre-colonial belief structures throughout the archipelago, the death or disappearance of a child was usually attributed to a spirit. The utter fear, not only of malignant spirits but also of a dead person and of his soul, is one of the most peculiar features of Philippine animism. In some areas, the envious spirits of the dead are also feared, for they, in their eagerness to participate in the farewell and final death feast, avail themselves of every occasion to injure the living in some mysterious but material way. Sickness, especially one in which the only symptoms are emaciation and debility, are attributed to their influence. These animist beliefs were the proof that children were inadvertently harmed by spirits when illness or death prevailed. When this changed from being a societal structure, into fear-based parenting is unknown. It should also be noted that in some areas, harming children by scaring them was previously seen as an grave offense. As mentioned in THE MANÓBOS OF MINDANÁO by JOHN M. GARVAN:

“On another occasion I ran after a child in play. The child out of fright rushed into the forest and hid. The same afternoon it was taken with a violent fever to which it succumbed a few days later. I was not in the settlement at the time of the death, and was not sorry, for it was reported to me that the father of the deceased child had said that he would have killed me. On my return to his settlement a few days later I visited the father for the purpose of having the case arbitrated. He broached the subject and demanded three slaves, or their equivalent, in payment for the death of his child, which was due, he firmly believed and asseverated, to the scare that I had given it.”

In essence, the Mumu is a common allusion to a supernatural character in the Philippines used by adults to frighten children into good behavior. Like the Bogeyman, it seems to have no specific appearance, and conceptions about it can vary drastically from household to household within the same community; in many cases, it has no set appearance in the mind of an adult or child, but is simply a non-specific embodiment of terror.

Story submitted by Joey Tibayan-Bayan: My great aunt would sometimes tell the story of the girl that was raped and killed near the sapa / swamp behind my grandparents house in Malolos. It was the 70s and I was Manila raised. I was a none believer. We were bored on this hot summer night, so we went to play near the stone wall blocking the swamp. We heard a faint groan …muuu muuu… behind the wall where the swamp was. We were curious so we climbed the wall to look. Under the fading light we saw long, unruly hair on top of a rock where the sound came from. My cousin and I screamed and ran as fast as we could back to the main house. Since then we never ventured swamp side of the house again and always referred to that incident as our encounter with the MUMU of Mojon.

The Term Mumu

The Kaufmann’s Visayan-English Dictionary (Hiligaynon Dictionary) which was published in 1934, defines “mamaw” and “mawmaw” as an evil spirit, bogy, bogey, goblin, hobgoblin, bugbear, bugaboo, a mischievous ghost.

I’ve found that Mumu has many pronunciations throughout the Philippines including, ‘momo’, ‘mamu’, ‘mamaw’, ‘mawmaw’, ‘mumo’ etc. This isn’t surprising in a country with some 187 native languages (according to ethnologue.com) — 80 by which no intercommunication is possible. In some regions, particularly the NCR, the mamaw differs from the mumu and is considered more of a monster. In the Visayan region, the different pronunciations don’t seem to delineate such distinctions. A contributing factor to these pronunciation variances is that Cebuano has three vowel phonemes, i.e., sounds that make a difference in word meaning, with four diphthongs: /aw/, /ay/, /iw/, /uy/, while Tagalog has 5 vowel phonemes.

It is commonly believed that Mumu is short for the term ‘multo’ (ghost or apparition of the dead) derived from the Spanish word muerto (meaning: “dead”). Another theory suggests that it comes from Mandarin 魔 (mó, “demon”), although I was unable to verify the connection of either theory. This term could have been introduced during 13th century trade with China who would have been in the late middle Chinese period of language where 魔 (mó, “demon”) had a similar meaning to 鬼 (guǐ, ghost).

One distinct characteristic of the Malayo-Polynesian languages is a tendency to use reduplication or repetition. In linguistics, reduplication means “the process by which the root or stem of a word, or part of it, is repeated.” Mumu would fall into this distinction, and either ‘multo’ or 魔 mó, could be the root or stem.

A Rite of Passage

When we hear about these kinds of stories we tend to think of them as archaic beliefs that our modern, intellectual society should have left behind. Yet even in this scientific and technological age, there are supernatural characters that are still presented to children as real. I personally don’t agree with the idea of parents scaring their children with the Mumu. Not only does it sound a little cruel to give them such terrifying images, but it feels like parents may be avoiding a longer disciplinary process towards good behavior. On the other hand, when we are faced with images of mythical creatures as we walk through a darkened path, or near a partially open door and emerge victorious, we are symbolically conquering our fears. Maybe supernatural characters like the Mumu, provide children with the important rite of passage of realizing they aren’t afraid any more. Perhaps this is one of those moments in a child’s life when they acknowledge their fear, but don’t do what it says, and instead overcome it. Until that moment, the Mumu remains a specter of judgment and fear designed to scare children into behaving and punishing those who don’t.

One common theme in my questioning about the Mumu is that those who were threatened with the Mumu as children were not upset with their parents — it is seen as more as a cultural myth that is just part of growing up in the Philippines.

ALSO READ: PUGOT MAMU: The Other Philippine Boogeyman

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.