Historically, these tattoos were given in proportion to your performance in battle, hunting, or heroic feats. “Warrior status was indicated in the Mountain Province and Kalinga not by clothing but by extravagant tattoos, and a man who tattooed without qualifying feats of valor could expect such divine retribution as illness or misfortune.”

I personally think it is wonderful that Whang-od is recognized today. I also feel saddened that the meaning has been taken out of the traditional practice and turned into a fad. She is an incredible artist, but I don’t know what is ‘right’ for preservation of a practice if the meaning is stripped away. Regardless, I support and embrace Whang-od’s decision to continue tattooing and training new apprentices. But is this preservation? I don’t know.

Pang-o-túb

While Kalinga tattoos have been growing in popularity and being preserved on the bodies of tourists, small Manobo communities have existed silently in North Cotabato, planting corn and tending banana trees for a living. Like many other indigenous groups, the Manobos of Arakan are fighting hard to keep their ways and traditions alive. And one of the traditions said to be slowly disappearing is tattooing.

The Manobos call tattooing pang-o-tub. In the book “The Manobos of Mindanao” by John M. Garvan, he wrote the following:

Pang-o-túb

After making an infinity of inquiries, I learned that tattooing is merely for the purpose of ornamentation. By a few I was given to understand that under the Spanish regime, when killing and capturing was rife, the tattooing was for the purpose of the identification of a captive. It was customary to change the name of a captive, and as he was sold and resold, the only way to identify him was by his tattoo marks.

Be that as it may, the practice seems to have at present no further significance than that of ornamentation. No therapeutic nor magical nor ceremonial effects are associated with it. Neither is it symbolic of prowess, nor distinctive of family, place, nor person, for two persons from different localities and groups may have the same designs.

No particular age is required for the inception of the process, but from my observation, corroborated by general testimony, I believe it is performed usually from the age of puberty onwards.

The operator is nearly always a woman, or a so-called hermaphrodite, who has acquired a certain amount of skill in embroidering. These professionals are not numerous, due, possibly, to the natural aversion felt by women for the sight of blood, as also to the fact that no remuneration is made for their services, though this last reason alone would not explain the paucity.

One meets occasionally among the peoples of eastern Mindanáo certain individuals who are known by a special name and who are reputed to be incapable of sexual intercourse. The individuals whom I saw were most feminine in their ways, preferring to keep the company of women and to indulge in womanly work rather than to associate with men.

The process is very simple. A pigment is prepared by holding a plate or an olla, over a burning torch made of resin until enough soot has collected. Then without any previous drawing, the operator punctures, to a depth of approximately 2 millimeters, the part of the body that is to be tattooed. The blood that flows from these punctures is wiped off, usually with a bunch of leaves, and a portion of the soot from the resin is rubbed vigorously into the wounds with the hand of the operator.

Saí-yung (Canarium villosum).

The process occupies a variable length of time, depending on the skill of the operator and on the endurance and patience of the subject. It is painful, but no such manifestations of pain are made as in teeth grinding. The portion tattooed is sensitive for about 24 hours, but no other evil consequences, such as festering, etc., follow as far as my observations go.

Without the aid of diagrams or pictures it is difficult to describe in an intelligible and comprehensive manner the numerous designs that are used in tattooing. Each locality may have its own distinct fashion, differing from the fashion prevalent in another region. And as the designs seem to be the result of individual whim and fancy it would be an almost endless task to describe all of them in detail. Suffice it to say in general that they follow in both nomenclature and in general appearance the figures embroidered on jackets, with the important addition of figures of a crocodile, and of stars and leaves, as is indicated by the names.

Bin-u-á-ja, (from bu-wá-ja, crocodile), gin-í-bang (from gí-bang, iguana) and bin-úyo (from bú-jo’, the betel leaf).

The figures are neither intricate nor grotesque, but simple and plain, displaying a certain amount of artistic merit for so primitive and so remote a people. On close inspection they show up in good clear lines, but at a distance they appear as nothing but dim blue spots or blotches. For durability they can not be surpassed. No means are known whereby to eradicate them. I compared tattoo marks on old men with those on young men and I could not discern any difference in the brightness nor in the preservation of the design.

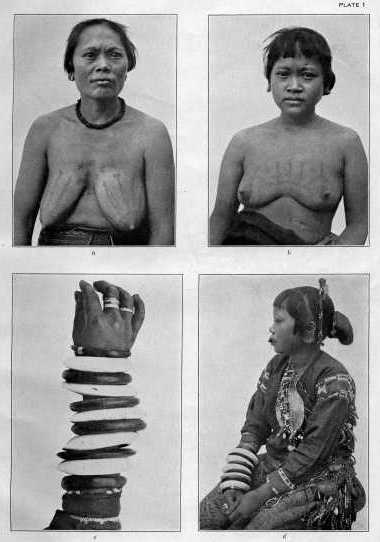

In men the portions of the body tattooed are the whole chest, the upper arms, the forearms, and the fingers. Women on the other hand, in addition to tattooings on those parts, receive an elaborate design on the calves, and sometimes on the whole leg.

The black pigment comes from the soot of a burnt hardwood tree called lawaan. This is wiped over the wound and won’t be washed off for a week.

Tattoos are supposed to give the Manobo strength. They say a tattooed Manobo does not tire easily, even after a whole day’s work in the fields.

The Manobo tattoos’ significance and purpose also go beyond the physical world. They believe that one’s tattoo serves as a guiding light in the afterlife. “Kapag namatay ka, madilim ang lahat. ‘Yung tattoo, parang ilaw na magdadala sa iyo sa lugar kung nasaan ang mga ninuno,” describes Datu Baguio.

Tattooing is not a common practice among the Manobo youth anymore. In fact, it is so rarely practiced that Lane Wilcken’s incredibly and comprehensively researched book “Filipino Tattoo: Ancient to Modern” gave no reference to the practice of pang-o-túb still being conducted today (his Facebook Page has since spoken about it). Still, Datu Baguio and the other Manobo tribe elders tirelessly push the pang-o-tub and their other customs forward. I wonder if there are other tribes still struggling to keep indigenous tattoo practices alive?

In Kalinga, preserving this tradition meant opening it up to outsiders and making the practice a tourist activity. I don’t know if the same will happen with the practice of pang-o-túb, although part of me really hopes it doesn’t. But that decision is up to the Manobo people and their artists.

SOURCES:

Photos by Karla Rimban and Billy Chavez/Alyx Ayn Arumpac/CM, GMA News

Pang-o-tub: The tattooing tradition of the Manobo Published August 28, 2012

THE MANÓBOS OF MINDANÁO by JOHN M. GARVAN United States Government Printing Office Washington : 1931

ALSO READ: The Beautiful History and Symbolism of Philippine Tattoo Culture

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.