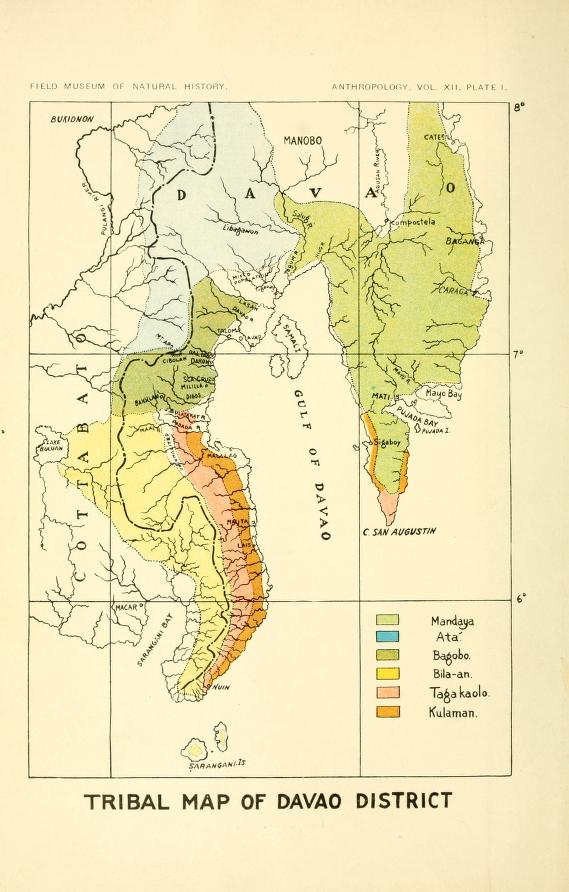

The Bagobo are one of the largest subgroups of the Manobo peoples. They comprise three subgroups: the Tagabawa, the Klata (or Guiangan), and the Ovu (also spelled Uvu or Ubo) peoples. The Bagobo were formerly nomadic and farmed through kaingin (slash-and-burn) methods. Their territory extends from the Davao Gulf to Mt. Apo. They are traditionally ruled by chieftains (matanum), a council of elders (magani), and female shamans (mabalian). The supreme spirit in their indigenous anito religions is Eugpamolak Manobo or Manama.

In 1904, the United States exhibited more than 1,100 native Filipinos, Negritos, Igorot, Moros, and Visayans at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri. Dubbed the “largest and finest colonial exhibit,” the Philippine Exhibition, though a huge success with the public, proved controversial because of its racist and imperialistic features, and the stigma it inflicted on Filipinos—a disgrace that is still felt after a hundred years. The Bagobo people were one of the peoples on display during the exhibition.

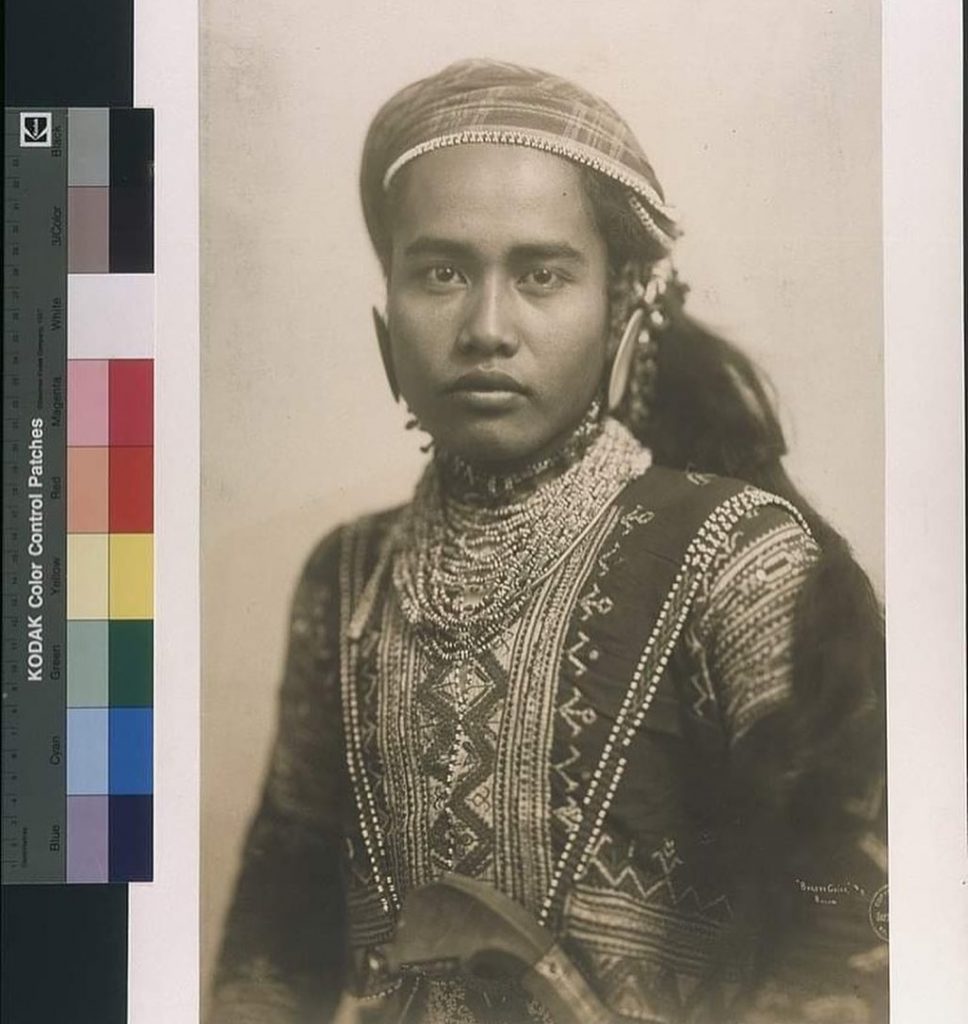

In the exhibit, Datu Bulon was the 19-year old chief of the Bagobo ‘Tribe,’ and was greatly admired for his handsome physique and elaborately ornamented costume. Each Bagobo performance concluded with Datu Bulon exhibiting his luxuriant growth of hair. He was one of the most photographed chieftains at the Fair. After the St. Louis Fair closed, it was said that he joined a troupe of performers that toured around the United States, performing in world expositions, state fairs, and amusement parks.

The contents of this article have been taken from the 1913 study The Wild Tribes of Davao District, Mindanao by Fay-Cooper Cole, and may not accurately reflect the beliefs of the modern people representing the Bagobo peoples. Beliefs among the Bagobo people can vary significantly from region to region. The bulk of the research in this study was conducted at the beginning of the 20th century and appears to have been gathered primarily on the west coast of Davao Gulf between Daliao and Digos. In 1908, as Catholicism spread, Eastern Mindanao was part of a vast religious movement – the Tungud movement – so these historical studies are very helpful benchmarks in the evolution of early tradition. Further, Fay-Cooper Cole note, “The influence of the neighboring tribes and of the white man on the Bagobo has been considerable. The desire for women, slaves, and loot, as well as the eagerness of individual warriors for distinction, has caused many hostile raids to be made against neighboring tribes. Similar motives have led others to attack them and thus there has been, through a long period, a certain exchange of blood, customs, and artifacts. Peaceful exchange of commodities has also been carried on for many years along the borders of their territory. With the advent of the Moro along the sea coast a brisk trade was opened up and new industries introduced. There seems to have been little, if any, intermarriage between these people, but their relations were sufficiently close for the Moro to exert a marked influence on the religious and civil life of the ‘wilder’ tribe, and to cause them to incorporate into their language many new words and terms.”

When you read “I” or any other similar subjective or nominative pronoun in the following text, it is referring to Fay-Cooper Cole. Since these are living beliefs, they have continued to evolve over the last one hundred years.

___________________________

SKETCH OF FUNDAMENTAL RELIGIOUS BELIEFS

The Bagobo believes in a mighty company of superior beings who exercise great control over the lives of men. Above all is Eugpamolak Manobo, also called Manama, who was the first cause and creator of all. Serving him is a vast number of spirits not malevolently inclined but capable of exacting punishment unless proper offerings and other tokens of respect are accorded them. Below them is a horde of low, mean spirits who delight to annoy mankind with mischievous pranks, or even to bring sickness and disaster to them. To this class generally belong the spirits who inhabit mountains, cliffs, rooks, trees, rivers, and springs. Standing between these two types are the shades of the dead who, after they have departed from this life, continue to exercise considerable influence, for good or bad, over the living.

We have still to mention a powerful class of supernatural beings who, in strength and importance, are removed only a little from the Creator. These are the patron spirits.

Guarding the warriors are two powerful beings, Mandarangan and his wife, Darago, who are popularly supposed to make their home in the crater of the volcano. They bring success in battle and give to the victors loot and slaves. In return for these favors they demand, at certain times, the sacrifice of a slave. Distensions, disasters, and death will be sure to visit the people should they fail to make the offering. Each year in the month of December the people are reminded of their obligation by the appearance in the sky of a constellation known as Balatik (Orion) and soon thereafter a human sacrifice doubtless takes place in some one or more of the Bagobo settlements.

A man to come under the protection of these two deities must first have taken at least two human lives. He is then entitled to wear a peculiar chocolate-colored kerchief with white patterns in it. When he has killed four he may wear blood-red trousers, and when his score has reached six he may don a full blood-red suit and carry a sack of the same color. Such a man is known as magani and his clothing marks him as a person of distinction and power in his village. He is one of the leaders in a war party; he is chosen by the datu to inflict the death penalty when it has been decreed; and he is one of the assistants in the yearly sacrifice. It is not necessary that those he kills, in order to gain the right to wear a red suit, be warriors. On the contrary he may kill women and children from ambush and still receive credit for the achievement, provided his victims are from a hostile village. He may count those of his townspeople whom he has killed in fair fight, and the murder of an unfaithful wife and her admirer is credited to him as a meritorious deed.

The workers in iron and brass, the weavers of hemp cloth, and the mediums or shamans—known as mabalian—are under the protection of special deities for whom they make ceremonies at certain times of the year.

MABALIAN

The mabalian just mentioned are people—generally women past middle life—who, through sufficient knowledge of the spirits and their desires, are able to converse with them, and to make ceremonies and offerings which will attract their attention, secure their good will, or appease their wrath. They may have a crude knowledge of medicine plants, and, in some cases, act as exorcists. The ceremonies which art performed at the critical periods of life are conducted by these mabalian, and they also direct the offerings associated with planting and harvesting. They are generally the ones who erect the little shrines seen along the trails or in the forests, and it is they who put offerings in the “spirit boxes” in the houses. Although they, better than all others, know how to read the signs and warnings sent by the spirits, yet, all of the people know the meaning of certain omens sent through the medium of birds and the like. The call of the limokon (a dove, Calcophops indica) is recognized as an encouragement or a warning and its message will be heeded without fail. In brief, every natural phenomenon and every living thing is caused by or is subject to the will of unseen beings, who in turn can be influenced by the acts of individuals. As a result everything of importance is undertaken with reference to these superior powers.

In case of illness a mabalian administers some simple remedy without any call on the spirits. If, however, the sickness does not yield readily to this treatment, it is evident that the trouble is caused by some spirit who can only be appeased by a gift, Betel nuts, leaves, food, clothing, and some article in daily use by the patient are placed in a dish of palm bark and on top of all is laid a roughly carved figure of a man. This offering is passed over the body of the patient while the mabalian addresses the spirits as follows. “Now, you can have the man on this dish, for we have changed him for the sick man. Pardon anything this man may have done, and let him be well again.” Immediately after this the dish is carried away and hidden so that the sick person may never see it again, for should he do so the illness would return.

When a woman gives birth, she is attended by two or more midwives or mabalian. She is placed with her back against an inclined board, while in her hands she holds a rope which is attached to the roof. With the initial pains, one of the midwives massages the abdomen, while another prepares a drink made from leaves, roots, and bark, and gives it to the expectant woman. The preparation of this concoction was taught by friendly spirits, and it is supposed to insure an easy delivery. Still another mabalian spreads a mat in the middle of the room, and on it places valuable cloths, weapons, and gongs, which she offers to the spirits; praying that they will make the birth easy and give good health to the infant. The articles offered at this time can be used by their former owners but as they are now the property of the spirits they must not be sold or traded. The writer was very anxious to secure an excellent weapon which had been thus offered. The user finally agreed to part with it but first he placed it beside another of equal value, and taking a piece of betel nut he rubbed each weapon with it a number of times, then dipping his fingers in the water he touched both the old and the new blades, all the time asking the spirit to accept and enter the new weapon. The child is removed by the mabalian who, in cutting the umbilical cord, makes use of the kind of knife used by the members of the child’s sex, otherwise the wound would never heal. The child is placed on a piece of soft betel bark, “for its bones are soft and our hands are hard and are apt to break the soft bones,” then water is poured over it and its body is rubbed with pogonok (medicine made of bark and rattan). The afterbirth is placed in a bamboo tube, is covered with ashes and a leaf, and the whole is hung against the side of the dwelling where it remains until it falls of its own accord or the house is destroyed. In Cibolan the midwife applies a mixture of clay and herbs called karamir to the eyes of all who have witnessed the birth “so that they will not become blind.” Having done this she gives the child its name, usually that of a relative, and her duties are over. As payment she will receive a large and a small knife, a plate, some cloth, and a needle.

BELIEFS CONCERNING THE SOUL, SPIRITS, ORACLES, AND MAGIC

There is some variance, in different parts of the Bagobo area, in the beliefs concerning the spirits or souls of a man. In Cibolan each man and woman is supposed to have eight spirits or gimokod, which dwell in the head, the right and left hands and feet, and other parts not specified. At death these gimokod part, four from the right side of the body, going up to a place called palakalángit, and four descending to a region known as karonaronawan.These places differ in no respects from the present home of the Bagobo, except that in the region above it is always day, and all useful plants grow in abundance. In these places the gimokod are met by the spirits, Toglái and Tigyama, and by them are assigned to their future homes. If a man has been a datu on earth, his spirits have like rank in the other life, but go to the same place as those of common people. The gimokod of evil men are punished by being crowded into poor houses. These spirits may return to their old home for short periods, and talk with the gimokod of the living through dreams, but they never return to dwell again on earth.

In the districts to the west of Cibolan the general belief is that there are but two gimokod, one inhabiting the right side of the body, the other the left. That of the right side is good, while all evil deeds and inclinations come from the one dwelling on the left. It is a common thing when a child is ill to attach a chain bracelet to its right arm and to bid the good spirit not to depart, but to remain and restore the child to health. In Malilla it is believed that after death the spirit of the right side goes to a good place, while the one on the left remains to wander about on earth as a buso, but this latter belief does not seem to be shared by the people of other districts.

Aside from the gimokod the Bagobo believe that there exists a great company of powerful spirits who make their homes in the sky above, in the space beneath the world, or in the sea, in streams, cliffs, mountains, or trees. The following is the list related by Datu Tongkaling, a number of mabalian, and others supposed to have special knowledge concerning these superior beings.

I. Eugpamolak Manobo, also called Manama and Kalayágan. The first and greatest of the spirits, and the creator of all that is. His home is in the sky from whence he can observe the doings of men. Gifts for him should be white, and should be placed above and in the center of offerings intended for other spirits. He may be addressed by the mabalian, the datu, and wise old men.

II. Tolus ka balakat, “dweller in the balakat (a hanger in which offerings are placed).” A male spirit who loves the blood, but not the flesh of human beings, and one of the three for whom the yearly sacrifice is made. Only the magani may offer petitions to him. He is not recognized by the people of Digos and vicinity.

III and IV. Mandarangan and his wife Darago. This couple look after the fortunes of the warriors, and in return demand the yearly sacrifice of a slave. They are supposed to dwell in the great fissure of Mt. Apo, from which clouds of sulphur fumes are constantly rising. The intentions of this pair are evil, and only the utmost care on the part of the magani can prevent them from causing quarrels and dissentions among the people, or even actually devouring some of them.

V. Taragómi/Taragomi. A male spirit who owns all food. He is the guardian of the crops and it is for him that the shrine known as parobanian is erected in the center of the rice field.

VI. Tolus ka towangan. The patron of the workers in brass and copper.

VII. Tolus ka gomanan. Patron of the smiths.

VIII. Baitpandi. A female spirit who taught the women to weave, and who now presides over the looms and the weavers.

IX. and X. Toglái, also called Si Niladan and Maniládan, and his wife Toglibon. The first man and woman to live on the earth. They gave to the people their language and customs. After their death they became spirits, and are now responsible for all marriages and births. By some people Toglái is believed to be one of the judges over the shades of the dead, while in Bansalan he is identified with Eugpamolak Manobo.

XI. Tigyama. A class of spirits, one of whom looks after each family. When children marry, the tigyama of the two families unite to form one who thereafter guards the couple. While usually well disposed they are capable of killing those who fail to show them respect, or who violate the rules governing family life.

XII. Diwata. A class of numerous spirits who serve Eugpamolak Manobo.

XIII. Anito. A name applied to a great body of spirits, some of whom are said formerly to have been people. They know all medicines and cures for illness, and it is from them that the mabalian secures her knowledge and her power. They also assist the tigyama in caring for the families.

XIV. Buso. Mean, evil spirits who eat dead people and have some power to injure the living. A young Bagobo described his idea of a buso as follows: “He has a long body, long feet and neck, curly hair, and black face, flat nose, and one big red or yellow eye. He has big feet and fingers, but small arms, and his two big teeth are long and pointed. Like a dog he goes about eating anything, even dead persons.” As already noted, the people of Malilla are inclined to identify the gimokod of the left side with this evil class.

XV. Tagamaling. Evil spirits who dwell in big trees.

XVI. Tigbanua. Ill disposed beings inhabiting rocks and cliffs in the mountains. These last two classes are frequently confused with the buso.

In addition to these, the old men of Malilla gave the following:

1. Tagareso. Low spirits who cause people to become angry and to do little evil deeds. In some cases they cause insanity.

2. Sarinago. Spirits who steal rice. It is best to appease them, otherwise the supply of rice will vanish rapidly.

3. Tagasoro. Beings who cause sudden anger which results in quarrels and death. They are the ones who furnish other spirits with human flesh.

4 and 5. Balinonok and his wife Balinsogo. This couple love blood and for this reason cause men and women to fight or to run amuck.

6. Siring. Mischievous spirits who inhabit caves, cliffs, and dangerous places. They have long nails and can be distinguished by that characteristic. They sometimes impersonate members of the family and thus succeed in stealing women and children, whom they carry to their mountain homes. The captives are not eaten but are fed on snakes and worms, and should they try to escape the siring will scratch them with their long nails.

Other spirits were named and described by individuals, but as they are not generally accepted by the people of the tribe they are not mentioned here.

The stars, thunder and lightning, and similar phenomena are generally considered as “lights or signs” belonging to the spirits, yet one frequently hears hazy tales such as that “the constellation Marara is a one-legged and one-armed man who sometimes causes cloudy weather at planting time so that people may not see his deformities,” or we are told that “the sun was placed in the sky by the creator, and on it lives an evil spirit who sometimes kills people. The sun is moved about by the wind;” again, “the sun and moon were once married and all the stars are their children.”

Despite repeated assertions by previous writers that the Bagobo are fire-worshippers no evidence was obtained during our visit to support the statement. The older people insisted that it was not a spirit and that no offerings were ever made to it. One mabalian stated that fire was injurious to a woman in her periods and hence it was best for her not to cook at such times; she was also of the opinion that fire was of two kinds, good and bad, and hence might belong to both good and bad spirits.

A common method used by the spirits to communicate with mortals is through the call of the limokon. All the people know the meaning of its calls and all respect its warnings. If a man is starting to buy or trade for an article and this bird gives its warning the sale is stopped. Should the limokon call when a person is on the trail he at ones doubles his fist and thrusts it in the direction from which the warning comes. If it becomes necessary to point backwards, it is a signal to return, or should the arm point directly in front it is certain that danger is there, and it is best to turn back and avoid it. When it is not clear from whence the note came, the traveler looks toward the right side. If he sees there strong, sturdy trees, he knows that all is well, but if they are cut or weaklings, he should use great care to avoid impending danger. When questioned as to why one should look only to the right, an old man quickly replied: “The right side belongs to you; the left side is bad and belongs to someone else.”

Sneezing is a bad omen, and should a person sneeze when about to undertake a journey, he knows that it is a warning of danger, and will delay until another time.

Certain charms, or actions, are of value either in warding off evil spirits, in causing trouble or death to an enemy, or in gaining an advantage over another in trading and in games. One type of charm is a narrow cloth belt in which “medicines” are tied. These medicines may be peculiarly shaped stones, bits of fungus growth, a tooth, shell, or similar object. Such belts are known as pamadan, or lambos, and are worn soldier-fashion over one shoulder. They are supposed to protect their owners in battle or to make it easy for them to get the best of other parties in a trade, A little dust gathered from the footprint of an enemy and placed in one of these belts will immediately cause the foe to become ill.

It is a simple matter to cause a person to become insane. All that is needed is to secure a piece of his hair, or clothing, place it in a dish of water and stir in one direction for several hours.

Father Gisbert (1886) relates the following method of detecting theft:

“There are not, as a rule, many thefts among the Bagobo, for they believe that a thief can be discovered easily by means of their famous bongat. That consists of two small joints of bamboo, which contain certain mysterious powders. He who has been robbed and wishes to determine the robber takes a hen’s egg, makes a hole in it, puts a pinch of the above said powder in it, and leaves it in the fire. If he wishes the robber to die he has nothing else to do than to break the egg; but since the thief may sometimes be a relative or a beloved person, the egg is not usually broken, so that there may be or may be able to be a remedy. For under all circumstances, when this operation is performed, if the robber lives, wherever he may be, he himself must inform on himself by crying out, ‘I am the thief; I am the thief,’ as he is compelled to do (they say) by the sharp pain which he feels all through his body. When he is discovered, he may be cured by putting powder from the other joint into the water and bathing his body with it. This practice is very common here among the heathens and Moros. A Bagobo, named Anas, who was converted, gave me the bongat with which he had frightened many people when a heathen.”

In Bansalan crab shells are hung over the doors of houses, for these shells are distasteful to the buso who will thus be kept at a distance.

I was frequently told of persons who could foretell the future by means of palmistry, but was never able to see a palmist at work, or to verify the information.

MYTHS

During my stay with this tribe I heard parts of many folk-tales, some chanted, others told with gravity, and still others which caused the greatest levity. My limited knowledge of the dialect and pressure of other work caused me to delay the recording of these tales until I should begin a systematic study of the language. Owing to unforeseen circumstances, that time never came, and it is now possible to give only the slightest idea of a very rich body of tales.[54]

Since this was written Laura Watson Benedict published an excellent collection of Bagobo Myths (Journal of American Folklore, 1913, XXVI. pp. 13-63.)

These stories are an attempt to account for the present order of things. In one tale we are told of an all-powerful being who created the earth and all that is. Other spirits and many animals inhabited the sky and earth which the creator had made. Of the latter only one, the monkey, is named. He and his kind, we are told, once inhabited and owned all the world, but were dispossessed by two human beings, Toglái and Toglibon, from whom all the people of the world are descended. After their death a great drought caused the people to disperse and seek out new homes in other parts. They journeyed in pairs and because of the objects which they carried with them, they are now known by certain names. One couple, for instance, carried with them a small basket called bira-an, and for this reason their children are known as Bira-an (Bila-an). From the time of the dispersion until the arrival of the Spaniards we learn that certain mythical heroes performed wonderful feats, in some cases being closely identified with the spirits themselves, in others making use of magic, the knowledge of which seems to have been common in those times.

The two following tales are typical of those commonly heard in a Bagobo gathering. The first was told by Urbano Eli, a Bagobo of Malilla.

“After the people were created a man named LumábEt was born. He could talk when he was one day old and the people said he was sent by Manama. He lived ninety seasons and when still a young man he had a hunting dog which he took to hunt on the mountain. The dog started up a white deer and LumábEt and his companions followed until they had gone about the world nine times when they finally caught it. At the time they caught the deer LumábEt’s hair was grey and he was an old man. All the time he was gone he had only one banana and one camote with him for food. When night came he planted the skin of the banana and in the morning he had ripe bananas to eat, and the camotes came the same way. When he had caught the deer LumábEt called the people to see him and he told them to kill his father. They obeyed him and then LumábEt took off his headband and waved it in the air over the dead man, and he at once was alive again. He did this eight times and at the eighth time his father was small like a little boy, for every time the people cut him in two the knife took off a little flesh. So all the people thought LumábEt was like a god.

“One year after he killed the deer he told all the people to come into his house, but they said they could not, for the house was small and the people many. But LumábEt said there was plenty of room, so all entered his house and were not crowded. The next morning the diwata, tigyama, and other spirits came and talked with him. After that he told the people that all who believed that he was powerful could go with him, but all who did not go would be turned into animals and buso. Then LumábEt started away and those who stayed back became animals and buso.

“He went to the place Binaton, across the ocean, the place where the earth and sky meet. When he got there he saw that the sky kept going up and down the same as a man opening and closing his jaws. LumábEt said to the sky ‘You must go up,’ but the sky replied ‘No.’ At last LumábEt promised the sky that if he let the others go he might catch the last one who tried to pass; so the sky opened and the people went through; but when near to the last the sky shut down and caught the bolo of next to the last man. The last one he caught and ate.

“That day LumábEt’s son Tagalion was hunting and caught many animals which he hung up. Then he said he must go to his father’s place; so he leaned an arrow against a baliti tree and sat on it. It began to grow down and carried him down to his father’s place, but when he arrived there were no people there. He saw a gun, made out of gold, and some white bees in the house. The bees said ‘You must not cry; we can take you to the sky,’ So he rode on the gun, and the bees took him to the sky and he arrived there in three days.

“One of the men was looking down on the land below, and all of the spirits made fun of him and said they would take out his intestines so that he would be like one of them and never die. The man refused to let them, and he wanted to go back home because he was afraid; so Manama said to let him go.

“The spirits took leaves of the karan grass and tied to his legs, and made a chain of the grass and let him down to the earth. When he reached the earth he was no longer a man but was an owl.”

(2) The second tale, which was recorded by P. Juan Doyle, S. J., is as follows:

“In one of the torrents which has its origin at the foot of Apo, there were two eels which, having acquired extraordinary magnitude, had no room in so little water, on account of which they determined to separate, each one taking a different direction in search of the sea or the great lakes. One arrived, happily, at the sea by the Padada river, and from it came eels in the sea. The other descending a torrent, swimming and confining himself as well as he might, enclosed in these narrow places, said to himself ‘I haven’t the slightest idea of what the sea is, but it appears to me that when I see before me an extraordinary clearness on a limpid surface, that must be the sea, and with one spring I will jump into it.’ So saying, he arrived at a point where the torrent formed a cascade. He noticed that it cut off the horizon and to his view it appeared of an extraordinary clearness; he thought he could swim there without limit, and at his pleasure, and that this, in fine, must be the sea. He darted into it, but the unhappy one was dashed against the rocks, and too fatigued to swim through the rough waters, he lost his life. His body lay there inert and formed undulations which are now the folds which the earth forms to the left of Mt. Apo.”

SOURCE: The Wild Tribes of Davao District, Mindanao, Fay-Cooper Cole, FIELD MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY PUBLICATION 170, ANTHROPOLOGICAL SERIES VOL. XII, No. 2.(1913)

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.