|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Kataw is the Visayan name for the “sirena.” As renowned folklorist Damiana Eugenio put it, “in a country where the belief in the sirena is common, it is disappointing not to find too many legends about her. Variously called sirena, kataw, duyong, and manatee in the legends, mermaids are generally described as beautiful women, with long curly black hair and black eyes. They are half women and half fish.” The Spanish loan-word sirena is the name generally given to Philippine mermaids.

According to Maximo Ramos, “The Visayans call her kataw. Her name means that she looks like a person. She is a pretty woman from head to waist. She is a fish with shiny scales below the waist. Her skin is light, her hair wavy and long. She lives in a beautiful house under the sea or beside a river, a lake, or a waterfall. She sits on a rock drying her long hair. She sings a sweet, sad song as she sits there. She makes the fisherman row his boat to her. Then she sinks his boat and gets him.”

In the controversial and historically disputed Pavon manuscripts, the catao is described as one of the “extinct animals of the island [Negros] according to a document of the year 1372”:

The catao. This was a fabulous fish, which they said inhabited the depths of the sea. It had, they said, the form of a very large fish, and was as large as a woman. One-half of its body resembled that of a woman with very beautiful hair, and the other half that of a fish with a tail…

It was said that there were no males among them, and I can almost assert that they have never been seen.

Referring to the catao, Pavon stated: When the sea was lonesome and calm, they [natives] said that it was singing its sad memories over and over in a sad harmonious voice.

An informant of Maximo Ramos, Bernabe H. Kapili, said that the word catao is understood in Leyte to mean ‘likeness of a person’ who has a fish tail.

In the past I have shared articles regarding the merfolk of the Philippines and the sirena of the Illocos, but I hadn’t presented anything on the kataw. Out of all the merfolk in the archipelago’s folkloric beliefs, the kataw is the most historically exciting.

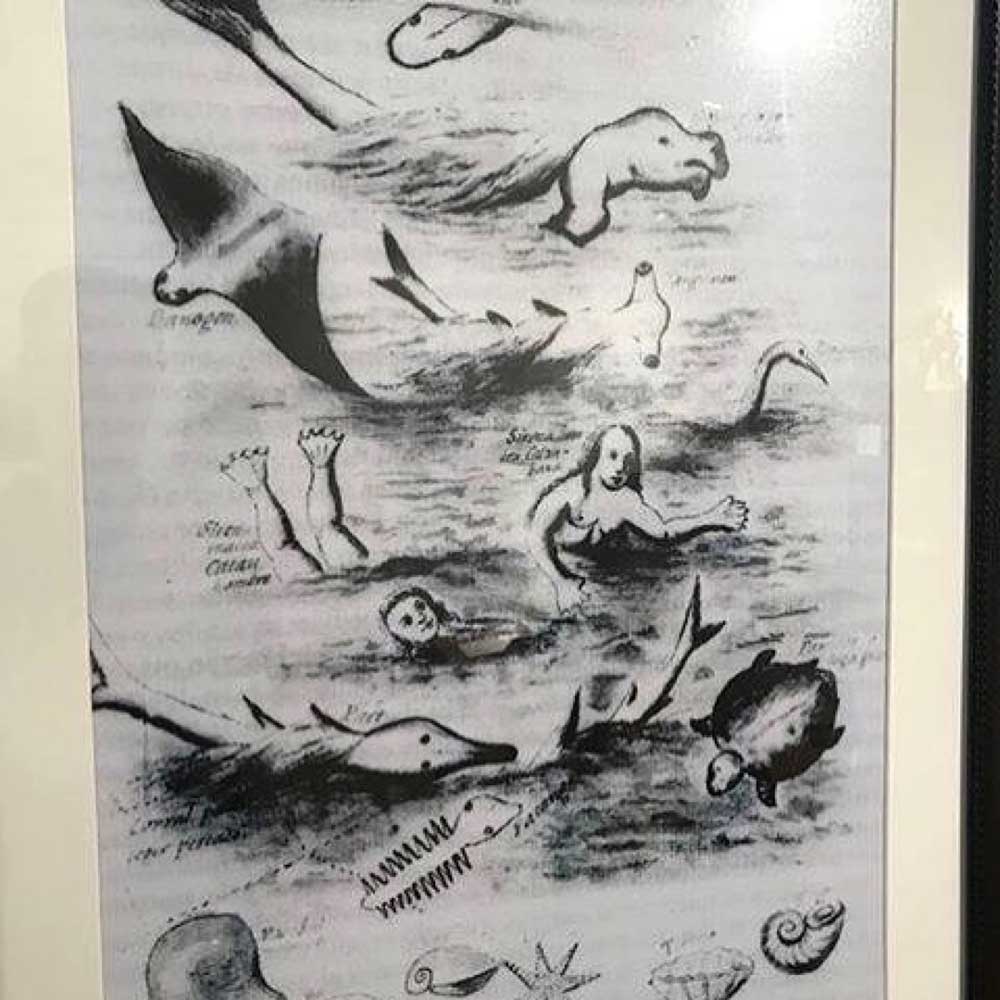

A most compelling discovery for me was coming across a drawing presented by Jesuit Fr. Francisco Ignacio Alzina. In his ‘Historia de las islas e indios de Visayas’ 1668 manuscripts, he included a male and female “catau” (kataw) – merman and mermaid. This isn’t to say that they are ‘real,’ but is a testament to how pronounced the folk belief must have been at that time.

PHOTO: Jordan Clark

The other marine animals that appear are a shark, dugong, ray, hammerhead shark, sawfish, turtle, molluscs, mother-of-pearl, and sea star – all of which are very real. It is very interesting to note that a differentiation between the kataw and dugong is made. It is often hypothesized that the dugong (sea mammal) was mistaken as a human form, spawning the mermaid legends.

My friends at Ang Panublion Museum in Roxas City, Capiz shared with me some images of commissioned traditional attire from the Panay Bukidnon where the hilt and sheath of a dagger was carved into a kataw.

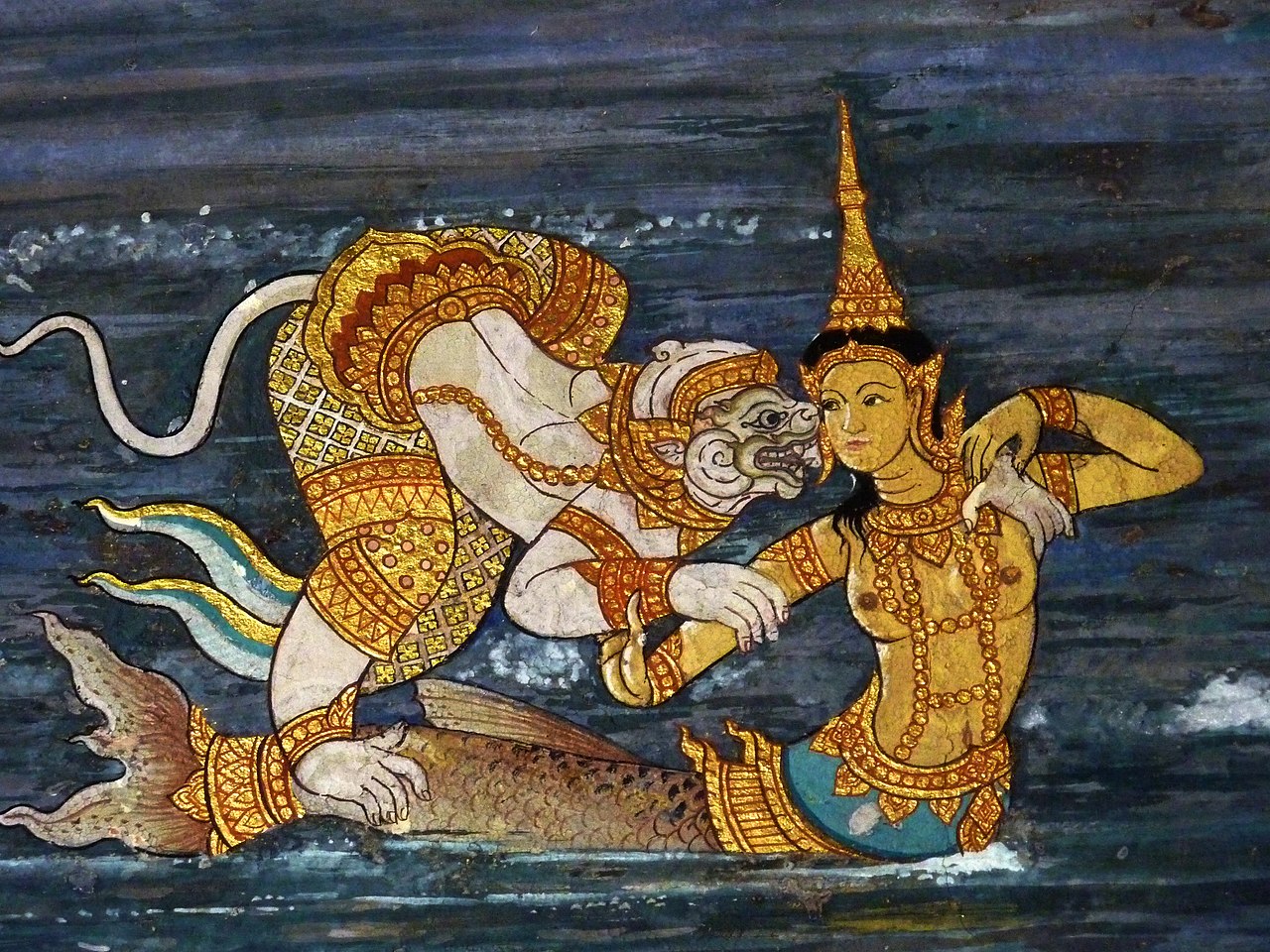

What immediately struck me upon seeing this dagger is how much it strayed from the Western motif of a mermaid (seen in the art at the top of this article), and instead leaned heavily towards a Hindu motif. If you have been following this page for any amount of time, you will know how often I bring up the Hindu epic of Ramayana. Most documented Philippine epics are based loosely, or firmly on this 2500 year old Indian literature (see: An Analysis of the Multi-Headed Beings of Philippine Myths and Epics). In the Ramayana, mermaids play an important role, particularly the leader of the mermaids, Suvarnamatsya, who is one of the many daughters of the ten headed demon Ravana. Hanuman (the hero), building a bridge across a water, discovered that he was hampered by mermaids stealing rocks. Suvarnamatsya falls in love with him.

We know that Philippine epics have evolved over time – even evolving from one chanter to the next. Perhaps the kataw may have featured in earlier incarnations of the Sugidanon epics of Panay, but were replaced by other characters as the story evolved over hundreds of years. We do know that Thai versions of the Ramayana have a mermaid character (Suvannamaccha), whose adornments share much in common with the kataw design of the Panay Bukidnon dagger. This connection shouldn’t be treated as canon, but it is another step away from the entirely false presumption that the Spanish introduced the concept of merfolk, or any of the other folkloric spirits bearing their loanword descriptors.

The Fisherman and the Nymph (Kataw Legend from Surigao)

Long ago when there were but a few inhabitants in the island of Catadman, there lived a man named Tomas. He lived with his wife, Doray, and their two daughters. He depended on farming and fishing for his livelihood.

One early morning, he took his basket, string, hook, and paddle and went fishing. The weather was calm and he quickly paddled his boat off into the middle of the sea. He caught plenty of fish. He went home early and sold all his catch. At mealtime, Doray remarked, “Tomas, how lucky you are today. You had a big catch.”

“Really, Doray,” Tomas answered, “I simply imagined that I was catching the fish I liked best and somehow I caught the best.”

Tomas went back to fish the next day. Again he had a big catch. “Maybe, Tomas,” Doray remarked, “your luck is due to the baby that I’m conceiving now. This is our third child; this will lead us to a better life in the days to come.”

For the third time, Tomas again went to sea. This time, he caught a huge fish. Then looking down deep into the water, he saw a very beautiful maiden with long hair and big black eyes. He was so frightened that he did not notice how its body looked. The maiden reached up to him. Tomas was speechless with fear. He paddled fast to the shore. When Doray, who was waiting for him on the shore saw him, Tomas was trembling. In his terror he forgot to haul out his catch. But Doray was not afraid and she told him, “That was a kataw whom you saw. Maybe the kataw wanted to make friends with you. She will give you plenty of fish and then we will at last have a little money always if it happens everyday.” Tomas did not say anything.

The next day, Tomas went to fish. He had a big catch. Then the kataw appeared and Tomas fainted. When he recovered, he was puzzled why he was in his nipa hut. Doray explained that some fishermen passed him by and brought him home. Tomas vowed he would never go to the sea again.

When Doray delivered her third child, she was a beautiful baby girl. She reared the baby tenderly and lovingly. At seven years old, the child still could not talk—like the kataw. Not minding the handicap of their youngest, Tomas and Doray still loved her. People said it was the child who brought luck to Tomas and Doray because since her birth, they had become rich.

Sources:

Ramos, Maximo D. (1990). Creatures of Midnight. Phoenix Publishing

Ramos, Maximo D. (1990). The Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology. Phoenix Publishing

Pavon, Transcipt no. 5-B,

Eugenio, Damiana. (2002). Philippine Folk Literature: The Legends. UP Press

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.