|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A few months ago, writer, fellow metalhead, and friend Karl R De Mesa sent me a link to Adamanta’s new video “Conquer.” From the thumbnail (and because it was from Karl), I had a feeling it was a metal song containing precolonial elements. Well, the song has been on my stay-list ever since, so I decided to take a deeper dive into the lyrics.

The song starts with heavy tribal drumming, then a wonderful Celtic folk melody comes in. While the video shows the band dressed in precolonial Philippine attire, the song goes VERY power metal and takes on a “pirate-y” sound. Power metal for me has always had a heavy and uplifting sound. A symphonic context is generally a part of it, and in the case of “Conquer” it includes a Celtic folk melody. Which brings me to the “pirate-y” sound of the song. Sea shanties are some of the more popular traditional songs found in Celtic music. That’s because they’re fun to sing. They were found mostly on European ships, and some had roots in lore and legend.

While the visuals and much of the lyrics are regarding the precolonial Visayans, it is clear that there is a nod to Viking culture. The song mentions “Bathala’s Gates” which is a play on “Valhalla’s Gates,” but also speaks of beer and ale, which did not exist in the precolonial Philippines in the traditional sense, but the comradery with drinking alcohol most certainly did. I’ve often felt that the Visayan seafaring warriors were of similar character and culture to the Vikings of Scandinavia. I’m not alone in this thought, it has been mentioned by several historians and researchers, both Western and Filipino.

I didn’t know how long I’d been waiting for a Visayan power metal band but I have often thought that early modern Visayans and Vikings had an awful lot in common

— The Work of Souls drops on 7/1 (@DGoweyAuthor) June 22, 2022

My thoughts about the song are confirmed on the bands official YouTube Channel: “Conquer came about from a thirst to connect with our roots. It’s both a prayer and promise to be strong and seek glory with the help of our ancestors. By channeling western European folk motifs, it’s a pull to those unfamiliar to Filipino culture that we, Visayans, were raiders, warriors, and seafarers similar to that of western Vikings.”

In a modern effort to push forward social movements, there has been an intense focus on themes of equity, inclusion, and arts in the precolonial Visayas. It is often swept under the rug that these communities were also intense and brutal – with honor and wealth accumulation based on raiding and slave-taking practices.

I found it interesting that part of the attire in the video was the hat seen above. Upon arrival in the archipelago, Pigafetta (Megallan’s chronicler) noted Queen Hara Humamay “…wore a large hat of palm leaves in the manner of parasol.” This highlights the unpopular fact that colorism existed in the precolonial Visayas – light skin was a sign of higher social class and beauty as there was no need to toil under the sun when you had slaves. Female royalty and binukot princesses were kept from sun exposure. This mindset existed, and continues to exist throughout all of Asia and was exacerbated in countries that were subjected to colonial invasion. To save myself from my critics, I will note that colorism in the precolonial Philippines was based on socioeconomics. Today, it is a pervasive and damaging mindset fueled by inflicted insecurity and exploitation.

I won’t get too much more into the attire seen in the video, but I thought it would be fun to break down the lyrics of “Conquer” and share informational aspects of the Visayan culture at the time of colonial contact. This is not meant in any way to hold Adamanta accountable as historians – although they did do a very impressive job!

We’ll sail across the seas

To the land of the dying and weak

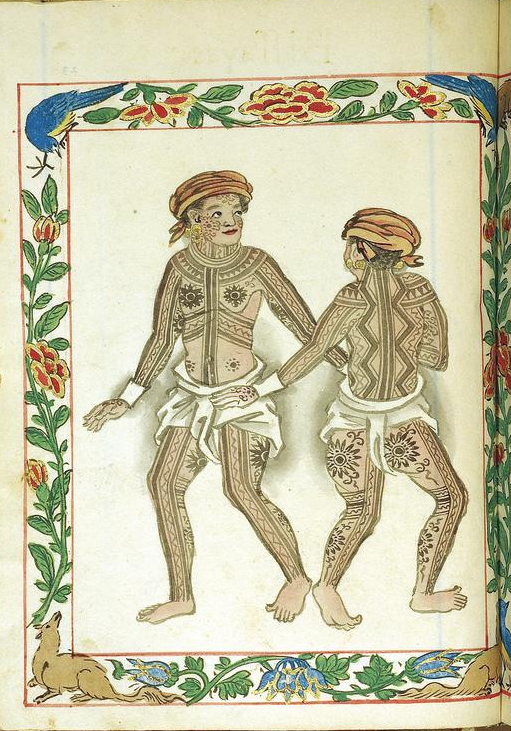

Among the early Visayans, warfare itself was seen as a kind of initiation rite into manhood: tigma was a youth’s first taste of war or sex, and tiklad was his first conquest either in battle or love. Tattoos were therefore required for public esteem by either sex. Those (who in todays view) would identify with a different gender, were socially accepted as mapuraw, natural-colored or without tattoos. Not surprisingly, the Visayan vocabulary included terms like kulmat, to strut around showing off new tattoos, and hundawas, stripped to the waist for bravado.

Tattooing itself was painful enough to serve as a test of manhood. For this reason, some men who were qualified as warriors postponed the operation until shamed into it. On the other hand, there were those who showed more macho mettle by adding labong scars on their arms with burning moxa, pellets of wooly fibers used in medical cautery. Still more rugged were those who submitted to facial tattooing. Indeed, those with tattoos right up to the eyelids constituted a warrior elite. Such countenances were truly terrifying and no doubt intimidated enemies in battle as well as townmates at home. Men would be slow to challenge or antagonize a tough with such visible signs of physical fortitude.

Tonight we take all the bottles you keep

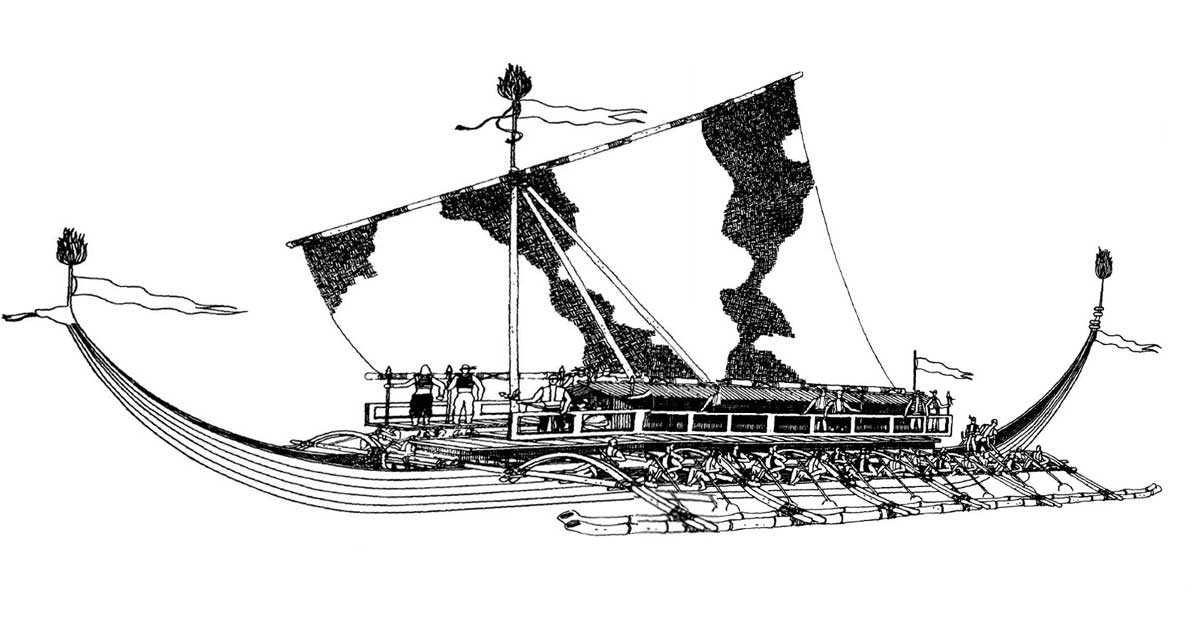

The most celebrated form of Visayan warfare was sea raiding, mangayaw, a word which appeared in all the major languages of the Philippines. There was a sacrifice that was performed on launching a warship for a raid called pagdaga, and it was considered most effective if the prow and keel were smeared with the blood of a victim from the target community. But karakoa cruisers were not designed simply for falling on undefended coastal communities: they were fitted with elevated fighting decks for ship-to-ship contact at sea. Such engagements were called bangga, and bangal was to pursue a fleeing enemy vessel. Besides slaves, preferred spoils of war were the bronze gongs and Chinese porcelains which constituted bahandi wealth.

Tonight we destroy your gods

For new worlds we seek

Of stories of old we will speak

When distinguishing different types of Visayan song, awit was used as a specific term for sea chanteys, which were called hilimbanganon in Panay. The cantor, himself pulling an oar—a paddle, actually—would lead off with an unrhymed couplet and the whole crew would respond in a heavy beat with a refrain (hollo) like “Hod-lo, he-le, hi-ya, he-le!” A good paraawit or parahele had a wide repertoire of tunes with different tempos, some of them handed down from generation to generation by fathers teaching their sons. The content of these sea chanteys, if not their actual wording, was also handed down from ancestral times and so perpetuated and promulgated Visayan traditions and values. More than one Spanish observer, commenting on the lack of written records, said that Filipino history and beliefs were preserved in the songs they heard while rowing boats.

We’ll face the day

We’ll rise with the seas

We’ll ride for the fountain

With passion we drink

Visayans did not drink alone, nor appear drunk in public. Drinking was done in small groups or in social gatherings where men and women sat on opposite sides of the room, and any passerby was welcome to join in. Women drank more moderately than men, and were expected to stretch their menfolk out, to sleep off any resulting stupor. But men were proud of their capacity.

Tomorrow we fight

We’ll face our destiny

Tomorrow we die

Professional mourners, generally old women, sang dirges which emphasized the grief of the survivors (who responded with keening wails), and eulogized the qualities of the deceased— the bravery and generosity of men, the beauty and industry of women, and the sexual fulfillment of either. These eulogies were addressed directly to the deceased and included prayers of petition: they were therefore a form of ancestor worship, one of such vigor that Spanish missionaries were never able to eradicate it.

In the case of a datu’s death, some of his slaves were sacrificed in the hope they would be accepted in his stead by the ancestor spirit who was calling him away. Or an itatanun expedition would be sent to take captives in some other community. These captives were sacrificed in a variety’ of brutal ways, though after first being intoxicated. In Cebu they were speared on the edge of the house porch to drop into graves already dug for them.

Renowned sea raiders sometimes left instructions for their burial. One in Leyte directed that his longon be placed in a shrine on the seacoast between Abuyog and Dulag, where his kalag could serve as patron for followers in his tradition. Many were interred in actual boats: the most celebrated case was that of a Bohol chieftain who was buried a few years before Legazpi’s arrival in a karakoa with seventy slaves, a full complement of oarsmen.

Tonight we drink a beer

There were basically five kinds of Visayan alcoholic beverages— tuba, kabarawan, intus or kilang, pangasi, and alak. Tuba was the sap of palms which fermented naturally in a few hours and soured quickly. Kabarawan was honey fermented with a kind of boiled bark. Intus or kilang was sugarcane wine, which improved with aging. Pangasi was rice wine or beer (that is, toddy), fermented with yeast, but could also be brewed from other grains like millet, all called pitarrilla by Spaniards. And alak was any of these beverages distilled into hard liquor. Alak was drunk from cups, but the others with reed straws from the porcelain jars in which they were brewed or stored. Pangasi was required for all formal or ceremonial occasions.

Drinking etiquette began with agda, exhorting some person, or diwata, to take the first drink. Gasa was to propose a toast to somebody’s health, usually of the opposite sex, and salabat was a toast in which the cup itself was offered, even carried from one house to another for this purpose.

And we will conquer for glory and fame

In the societies that produced Philippine epics power and prestige were based on the ownership and the control of slave labor. Thus Visayan heroes who were celebrated as karanduun—that is, worthy of kandu (folk epic) acclaim— would have won their reputations in real life on pangayaw slave raids. As one kandu says of its heroine, “You raid with your eyes and capture many, and with only a glance you take more prisoners than raiders do with their pangayaw”

The subject matter of Visayan stories was the heroic exploits of ancestors, the valor of warriors, or the beauty of women, or even the exaltation of heroes still living.

The amber nectar it flows in our veins

Grab your fear and burn it with ale

This is the way to Bathala’s Gates

I found it interesting that Adamanta picked up the lesser known fact that Bathala was not just a deity to the Tagalogs, but also the Southern Bisayans, particularly Cebu, and some Bisayan areas of Mindanao. This can be seen in the Cebuano myths of Bakunawa and others stories from the region.

Throughout most of the Visayas, the departing soul was delivered to the land of the dead, Saad or Sulad, by boat. On the other shore, the kalag (soul) would be met by relatives who had predeceased him, but they accepted him only if he was well ornamented with gold jewelry. If rejected, he remained permanently in Sulad unless reprieved by the god Pandaki in response to rich paganito offered by his survivors. In Panay, Magwayen was the boatman; the lords of the underworld were Mural and Ginarugan; and Sumpos, the one who rescued the souls on Pandaki’s behalf and gave them to Siburanen who, in turn, brought them to where they would live out their afterlife—Mount Madyaas for the Kiniray-a, or Borneo for the Cebuanos and Boholanos.

And we will fight for the glorious day

With battle axes Ynaguinid’s rage

I don’t know of any records that Visayans used battle axes, but bladed weapons were an ordinary part of Visayan male costume, at least a dagger or spear. If bound with gold or set with gems, these constituted an essential part of a datu’s personal jewelry. Daggers, knives, swords, spears and javelins, shields and body armor were found everywhere in the precolonial Philippines.

The worship of the Visayan war deities was an important part of the formidable Visayan warrior culture. In Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas (June 1582), Miguel de Loarca states, “When they go to war or on a plundering expedition, they offer prayers to Varangao (Barangaw), who is the rainbow, and to their gods, Ynaguinid and Macanduc. For the redemption of souls detained in the inferno above mentioned, they invoke also their ancestors, and the dead, claiming to see them and receive answers to their questions.”

Grab your fear the strong will prevail

Follow the brave to Bathala’s Gates

Your old gods will weep

Your daughters and sons we will keep

Raids were also mounted to carry off choice ladies as brides, especially the daughters of men with whom it was advantageous to establish collateral ties. Female slaves were also made to dance naked for visiting royalty.

For they like we

The gates they will see

And drown in the fountain

With passion we drink

Drinking was commonly called pagampang, conversation; and neither business deals, family affairs, nor community decisions were discussed without it.

_______

While this is an opinion piece, much of the information was gleaned from William Henry Scott’s ‘Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society’ released through Ateneo de University Press.

Follow Adamanta on Facebook or Instagram.

Attire for the video was provided through Karakoa Productions.

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.