The Manobo are several people groups who inhabit the island of Mindanao in the Philippines. They speak one of the languages belonging to the Manobo language family. Their origins can be traced back to the early Malay peoples who came from the surrounding islands of Southeast Asia. Today, their common cultural language and Malay heritage help to keep them connected.

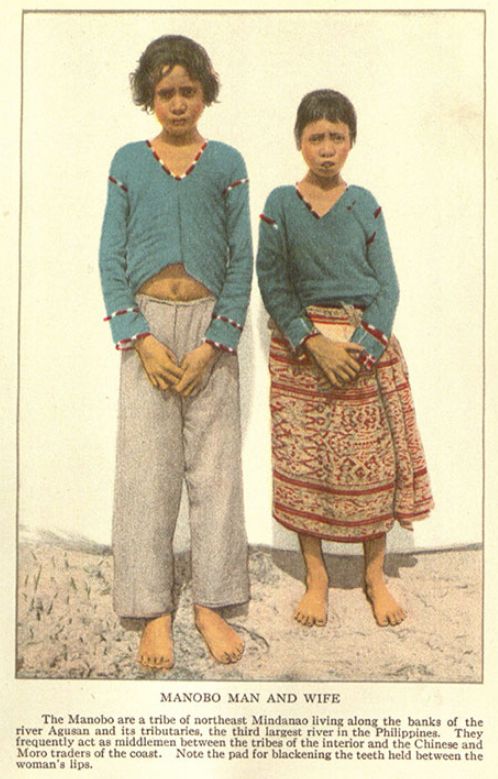

The Manobo cluster includes eight groups: the Cotabato Manobo, Agusan Manobo, Dibabawon Manobo, Matig Salug Manobo, Sarangani Manobo, Manobo of Western Bukidnon, Obo Manobo, and Tagabawa Manobo. The groups are often connected by name with either political divisions or landforms. The Bukidnons, for example, are located in a province of the same name. The Agusans, who live near the Agusan River Valley, are named according to their location.

The eight Manobo groups are all very similar, differing only in language and in some aspects of culture. The distinctions have resulted from their geographical separation.

The contents of this article have been taken from the 1931 memoir THE MANÓBOS OF MINDANÁO by John M. Garvan, and may not accurately represent the beliefs of the modern people representing the Manobo language group. For instance, if one were to look at the religion and beliefs of the Manobo around Mt. Apo (see: A voice from Mt. Apo, Melchor Bayawan, Linguistic Society of the Philippines, 2005) much would be unrecognizable from the contents of this article. The bulk of the research in this study was conducted at the beginning of the 20th century and appears to have been gathered primarily in the Agusan Valley. Beliefs among Manobo language groups vary from region to region. Since these are living beliefs, they have continued to evolve over the last one hundred years. Human sacrifice had ceased before this research was conducted. John Garvan never witnessed a human sacrifice and only accounts for instances based on second hand recollections and the research of earlier chroniclers. Human sacrifices do seems to have occured on Mindanao, but this writer has not yet studied the topic enough to expand on its extent.

When you read “I” or any other similar subjective or nominative pronoun, it is referring to John Garvan.

_______________________________________________

THE SACRIFICE OF A PIG

Religion is so interwoven with the Manóbo’s life, as has been constantly stated in this monograph, that it is impossible to group under the heading of religion all the various observances and rites that properly belong to it. I will now give an account of the sacrifice of a pig that took place on the Kasilaían River, central Agúsan, for the recovery of a sick man. This sacrifice may be considered typical of the ordinary ceremony in which a pig is immolated, whether it be for the recovery of a sick man or to avert evil or to solicit any other favor.

I arrived at the house at about 4 p.m. Near the pole leading up to the house stood the newly erected rectangular bamboo stand (Añg-kan). On this, with a few palm fronds arched over it, was tightly bound the intended victim, a fat castrated pig. Within a few yards of this had been erected the small house-like structure (Ka-má-lig). It contained several plates full of offerings of uncooked rice and eggs, which had been placed there previously. The ceremonies began shortly after my arrival. Three women of the priestly order sat down near the ceremonial house and prepared a large number of betel-nut quids for their respective deities, but the spectators never ceased for a moment to ask for a share of them. Finally, however, the quids were prepared and placed on the sacred plates, seven to each plate. Then one of the priestesses placed a little resin upon a piece of bamboo and, calling for a firebrand, placed it upon the resin. The other two priestesses, seizing in each hand a piece of palm branch, proceeded to dance to the sound of drum and gong. They were soon joined by the third officiant. All three danced for some five minutes until, as if by previous understanding, the gong and drum ceased, and one of the priestesses broke out into the invocation. This consisted of a series of repetitions and circumlocutions in which her favorite deities were reminded of the various sacrifices that had been performed in their honor from time immemorial; of the number of pigs that had been slain; of the size of these victims; of the amount of drink consumed; of the number of guests present; and of an infinity of other things that it would be tedious to recount. This was rattled off while the spectators were enjoying themselves with betel-nut chewing and while conversation was being carried on in the usual vehement way. Then the drum and gong boomed out again and the three priestesses circled about in front of the ceremonial shed for about five minutes, after which comparative quiet ensued and another priestess took up the invocation. During her prolix harangue to the spirits the other two busied themselves, one in rearranging the offerings in the little shed, the other in lighting more incense, while the spectators continued their prattle, heedless of the services. After an interval of some 10 minutes the sacred dance was continued, the priestesses circling and sweeping around with their palm branches waving up and down as they swung their arms in graceful movements through the air. This continued for several minutes, until one of them stopped suddenly and began to tremble very perceptibly. The other two continued their dance around her, waving their palm fronds over her. The trembling increased in violence until her whole body seemed to be in a convulsion. Her eyes assumed a ghastly stare, her eyeballs protruded, and the eyelids quivered rapidly. The drum and gong increased their booming in volume and in rapidity, while the dancers surged in rapid circles around the possessed one, who at this period was apparently unconscious of everything. Her eyes were shaded with one hand and a copious perspiration covered her whole body. When finally the music and the dancing ceased her trembling still continued, but now the loud belching could be heard. No words can describe the vehemence of this prolonged belching, accompanied as it was by violent trembling and painful gasping. The spectators still continued their loud talking with never a care for the scene that was being enacted, except when some one uttered a shrill cry of animation, possibly as menace to lurking enemies, spiritual or other.

It was some 10 minutes before the paroxysm ceased, and then the now conscious priestess broke forth into a long harangue in which she described what took place during her trance, prophesying the cure of the sick man, but advising a repetition of the sacrifice at a near date, and uttering a confusion of other things. During all this time frequent potations were administered to the spectators, so that in the early night everyone was feeling in high spirits.

After the first priestess had emerged fully from the trance the drum and gong resounded for the continuation of the dance. In turn the other priestesses fell under the influence of their special divinities and gave utterance to long accounts of what had passed between them. It was at a late hour of the night that the whole company retired to the house, leaving the victim still bound upon his sacrificial table.

The religious part of the celebration was then abandoned, for the priestesses took no further part. Social amusements, consisting of various forms of dancing, mimetic and other, were performed for the benefit of the attendant deities and finally long legendary chants(Túd-um) by a few priests consumed the remainder of the night.

Next morning at about 7 o’clock the ceremonies were resumed by the customary offering of betel nut and by burning of incense, but instead of dancing before the small religious house the three priestesses, joined by a priest, took up their position near the sacrificial table on which the victim had remained since the preceding day. The invocations were pronounced in turn, followed by short intervals of dancing. During these invocations the victim was bound more securely, and a little lime was placed on its side just over the heart. The priest then placed seven betel-nut quids upon the body of the pig and made a final invocation. A rice mortar was placed at the side of the sacrificial table, a relative of the sick man stepped upon it, and, receiving a lance from the hands of the male priest, poised it vertically above the spot designated by the lime and thrust it through the heart of the victim.

One of the female priestesses at once placed an iron cooking pan under the pig and caught the blood as it streamed out from the lower opening of the wound. Applying her mouth to the pan she drank some of the blood and gave the pan to a sister priest (not infrequently the blood is sucked from the upper wound. This is a custom more prevalent among the Mandáyas than among the Manóbos). At the same time a little was given to the sick man, who drank it down with such eager haste that it ran upon his cheeks. One of the priestesses then performed blood lustration by anointing the patient’s forehead with the remainder of the blood. A few others, of whom I was one, had these bloody ministrations performed on them.

The priest and priestesses at this period presented a most strange spectacle. With faces and hands besmirched with clotted blood, they stood trembling with indescribable vehemence. Their jingle bells tinkled in time with the movement of their bodies. The priestesses recovered from their furious possession after a few minutes, but not so the male priest, for to prevent himself from collapsing completely he clutched a near-by tree, shading his eyes with his bloodstained hand. The drum and gong came into play again and the priestesses took up the step, circling around their entranced companion and addressing him in terms that on account of the rattle of the drum and the clanging of the gong could not be heard. He finally emerged, however, all dazed and covered with perspiration. Through him a diuáta announced the recovery of the patient, at which yells of approval rang out, and then began a social celebration consisting of dancing and drinking. This was continued till the hour for dinner, when the victim was consumed in the usual way.

In this instance, as in many others witnessed, the sick man recovered, and with a suddenness that seemed extraordinary. This must be attributed to the deep and abiding faith that the Manóbo places in his deities and in his priests. The circumstances of the sacrifice are such as to inspire him with confidence and, strong in his faith, he recovers his health and strength in nearly every case.

RITES PECULIAR TO THE WAR PRIESTS

(1) The betel-nut tribute to the gods of war.

(2) The supplication and invocation of the gods of war.

(3) The betel-nut offering to the souls of the enemies.

(4) The various forms of divination.

(5) The ceremonial invocation of the omen bird.

(6) The tagbúsau’s feast.

(7) Human sacrifice.

The first two ceremonies differ from the corresponding functions performed by the ordinary priests in only two respects, first that they are performed in honor of the war spirits, and secondly that the invocation includes an interminable list of the names of those slain by the officiating warrior chief and by his ancestors for a few generations back.

The sacred dance for the entertainment of the attending divinities with which this invocation and supplication is repeatedly interrupted will be described later on.

THE BETEL-NUT OFFERING TO THE SOULS OF THE ENEMIES

The ceremony is performed only before an expedition, with a view to securing the good will of souls of the enemies who may be slain in the intended fray. As was set forth before, souls, or departed spirits, seem to have a grievance against the living, and are wont to plague them in diverse ways. Now, in order to avoid such ill will as might follow the separation of these spirits from their corporal companions, a ceremony is performed by the warrior priest in the following way: He orders an offering of rice to be set out upon the river bank, or on the trail over which the spirits are expected to wing their way, and hastens to invite them to a conference. Then a number of pieces of betel leaf are set out on a shield, so that each soul or spirit has his portion of betel leaf, his little slice of betel nut, and his bit of lime. Then the warrior chief, or some one else at his bidding, addresses the souls without making it known that an attack is soon to be made – I was informed that a sometime friend or distant relative of the enemy is generally selected for this task. It is then explained to these spirits that they are invited to partake of the offering in good will and peace, that the warrior priest’s party has a grievance against their enemies, and that some day they may be obliged to redress the matter in a bloody way. The souls next are urged to forego their displeasure, should it become necessary at any time to redress the wrongs by force and possibly slay the authors of them. The invisible souls are then supposed to partake of the offering and to depart in peace as if they understood the whole situation.

There is an incident, which is said to occur during the above ceremony, that deserves special mention, as it illustrates very pointedly the spirit in which the ceremony is performed. All arms are said to be placed upon the ground and carefully covered with the shields in such a way that the spirit guests will be unable to detect their presence on their arrival. The betel-nut portions are placed upon one of the upper shields.

VARIOUS FORMS OF DIVINATION

The betel-nut cast (Ba-lís-kad to ma-má-on) –This form of divination is never omitted, according to all accounts. In the instance which I witnessed the procedure was as follows: The leader of the expedition invoked the tagbúsau, informing him that each of the quids represented one of the enemy, and beseeching him (or them) to indicate by the position of these symbols after the ceremony the fate of the enemy. The warrior priest or his representative, lifting up the shield with one hand under it, and one hand above it, turned it upside down with a rapid movement, thus precipitating the quids on the floor. Now those that fell vertically under the shield represented the number of the enemy who would fall into their clutches, while those that lay without the pale of the shield represented the individuals who would escape, and to whose slaughter accordingly they must devote every energy. There are numerous little details in this, as in most other forms of divination, each one of which has an interpretation, subject, it would appear, to the vagaries of each individual augur.

Divination from the báguñg vine.–Before leaving the point from which it has been decided to begin the march two pieces of green rattan, the length of the middle finger and about 1 centimeter thick, are laid upon the ground parallel to each other and about 2.5 centimeters apart. One of these stands for the enemy and the other for the attacking party. A firebrand is then held over the two until the heat causes one of them to warp and twist to one side or the other. Thus if the strip that represents the enemy were to begin to twist over toward that of the aggressors, while that of the latter twists away from the former, the omen would be bad, for it would denote the flight of the assaulting party. Should, however, the rattan of the aggressors twist over and fall on the other, the omen would be auspicious and the march might be entered upon.

The various twists and curls of these strips of rattan are observed with the closest attention and interpreted variously. Should the omen prove ill, the tagbúsau must be invoked and other forms of divination tried until the party feels assured of success.

Divination from báya squares.–The báya is a species of small vine, a fathom of which is cut by the leader into pieces exactly the length of the middle finger. These pieces are then laid on the ground in squares. Should the number of pieces be sufficient to constitute complete squares without any remainder the omen is bad in the extreme, but should a certain number of pieces remain the omen is good. Thus if one piece remains the attack will be successful and of short duration. If two remain, the outcome will be the same, but there will be some delay; and if three remain, the delay will be considerable, as it will be necessary to construct ladders (Pa-ga-hag-da-nán).

When any of the omens taken by one of the above forms of divination prove unpropitious, the tagbúsau must be invoked and other divinatory methods tried until the party is satisfied that a reasonable amount of success is assured. But should the omens indicate a failure or a disaster, the expedition must be put off or a change made in the party. Thus, for instance, the bad luck (Paí-ad) might be attributed to the presence of one or more individuals. In that case these persons are eliminated and the omens repeated. It is needless to say that the observance of all the omens necessary for an expedition, together with the concomitant ceremonies, may occupy as much as three days and nights.

INVOCATION OF THE OMEN BIRD (Pan-áu-ag-táu-ag to li-mó-kon)

Though at the beginning of ordinary journeys the consultation of the omen bird is of primary importance, yet before a war expedition it acquires a solemnity that is not customary on ordinary occasions. This ceremony is the last of all those that are made preparatory to the march.

The warrior priest turns toward the trail and addresses the invisible turtledove, beseeching it to sing out from the proper direction and thereby declare whether they may proceed or not. In one of the instances that came under my personal observation a little unhulled rice was placed upon a log for the regalement of the omen bird, and a tame pet omen bird in an adjoining house was petted and fed and asked to summon its wild mates of the encircling forest to sing the song of victory. Many of the band imitate the turtle bird’s cry as a further inducement to get an answer from the wild omen birds that might be in the neighborhood. This is done by putting the hands crosswise, palm over palm and thumb beside thumb. The cavity between the palms must be tightly closed, leaving open a slit between the thumbs. The mouth is applied to this slit and by blowing in puffs the Manóbo can produce a sound that is natural enough to elicit in many cases response from a turtledove that may be within hearing distance. In fact, I have known the birds to approach within shooting distance of the artificial sounds.

THE TAGBÚSAU’S FEAST

In the ceremonies connected with, the celebration in honor of his war lord the warrior priest is the principal personage, but he is usually assisted by several of the chief priests of the ordinary class. Such is the general account, and such was the procedure in the ceremony that I witnessed in 1907, of which the following are the main details and which will serve as a general description of the ceremony:

The appurtenances of the ceremony were identical with those described before under ceremonial accessories, except that a piece of bamboo, about 30 centimeters long, parted and carved into the form of a crude crocodile with a betel-nut frond hanging from it, was suspended in the diminutive offering house referred to so many times before. Objects of this kind, like this piece of bamboo, have a mouthlike form and vary from 30 to 60 centimeters in length. They are, as it were, ceremonial salvers on which are set the offerings of blood and meat and gíbañg (nape of the neck; a pig in this case) for the war deities.

In the ceremony that I am describing I noticed a plate of rice set out on an upright piece of bamboo, the upper part of which had been spread out into an inverted cone to hold the plate. The pig had been bound already to its sacrificial table, but was ceaseless in its cries and in its efforts to release itself. Several war and ordinary priests, covered with all their wealth of charms and ornaments, were scattered throughout the assembly. The war priests particularly presented an imposing appearance, vested in the blood-red insignia of their rank. Around their necks were thrown the magic charm collars, with their pendants of shells, crocodile teeth, and herbs.

About 5 o’clock in the afternoon of the day in question the ceremony was ushered in in the usual way by several male and female priests. The warrior priests did not take part till the following day, though during the night they chanted legendary tales of great Manóbo fights and fighters. The following morning, however, they led the ceremonies.

During the whole performance there seemed to be no established system or order. Both warrior priests and others took up the invocation and the dance as the whim moved or as the opportunity allowed them. One noteworthy point about the ceremony was the ritual dance of the warrior priests in honor of their war deities. Attired as they were in the full panoply of war, with hempen coat and shield, lance, bolo, and dagger, they romped and pirouetted in turns around the victim to the wild war tattoo of the drum and the clang of the gong. Imagining the victim to be some doughty enemy of his, the dancer darted his lance at it back and forth, now advancing, now retreating, at times hiding behind his shield, and at others advancing uncovered as if to give the last long lunge. Under the inspiration of the occasion their eyes gleamed with a fierce glare and the whole physiognomy was kindled with the fire of war. The spectators on this particular occasion maintained silence and attention and manifested considerable fear. It is believed that the warrior priest, being under the influence of his war god, is liable to commit an act of violence.

At the time I did not understand the tenor of the invocations that followed each dance, but was informed that they are such as would be expected on such an occasion, namely, an invitation to the spirits of war to partake of the feast and a prayer to them to accompany the party and assist them in capturing their enemies.

When the moment for the sacrifice arrived the leader of the party, the chief warrior priest, danced the final dance and, stepping up to the pig, plunged his spear through its heart, and, applying his mouth to the wound, drank the blood. Several of the other priests caught the blood in plates and pans and partook of it in the same manner. The leader put the blood receptacle under the wound and allowed some of the blood to flow into it. He then returned it to the diminutive offering house. The ordinary priests fell into the customary trance, but the war-priest, together with several of the spectators, took the blood omen. Apparently this was not favorable, for they ordered the intestines to be removed at once and examined the gall bladder and the liver.

The priests emerged from their trance and no further ceremonies were performed except the taking of omens. This occupied several hours and was performed by little groups, even the young boys trying their hand at it.

When the pig had been cooked it was set out on the floor and was partaken of in the usual way. There was little brew on hand. I learned that on such occasions it is not customary to indulge to any great extent in drinking.

The party expected to begin the march that afternoon; but as the scouts had not returned they waited until the next morning.

When the march was about to begin, and while the party still stood on the river bank, the leader wrenched the head off a chicken and took observations from the blood and intestines. These were not as satisfactory as was desired, but were considered favorable enough to warrant beginning the march tentatively. Upon the entrance of the party into the forest the omen bird was invoked; its cry proved favorable, and the march began.

HUMAN SACRIFICE (Hu-á-ga)

I never witnessed a human sacrifice nor was I ever able to verify the facts in the locality in which one had occurred, but I have no doubt that such sacrifices were made occasionally by Manóbos in former times.

It is not strange that a custom of this kind should exist in a country where a human being is a mere chattel, sometimes valued at less than a good dog. When it is considered that in Manóboland revenge is not only a virtue but a precept, and often a sacred inheritance, it stands to reason that to sacrifice the life of an enemy or of an enemy’s friend or relative would be an act of the highest merit. From what I have observed of Manóbo ways I can readily conceive the satisfaction and glee with which an enemy would be offered up to the war deities of a settlement, slowly lanced or stabbed to death, and then the heart, liver, and blood taken ceremonially. A very common expression of anger used by one Manóbo to another is “huagon ka,” that is, “May you be sacrificed.”

I find verbal evidences of human sacrifices in those regions only that are near to the territory of the Bagóbos and the Mandáyas. This leads me to think that the custom is either of Bagóbo or of Mandáya origin.

The Jesuit missionary Urios (Cartas de los PP. de la Compañía de Jesús, Cuaderno V, letter from Father Saturnine Urios, Patrocinio, Sept. 16, 1881) makes mention of the case of Maliñgáan who lived on the upper Simúlao, contiguous to the Mandáya country. In order to cure himself of a severe illness he had a little girl sacrificed. Urios describes the punitive expedition sent out against him, and the death of Maliñgáan by his own hand.

I have heard of numerous cases, especially in the region at the headwaters of the Báobo, Ihawán, and Sábud Rivers. One particular case will illustrate the manner in which the ceremony is performed. My authority for the account is one who claimed to have participated in the sacrifice.

A boy slave, who belonged to the man that arranged the sacrifice, was selected. The slave was given to understand that the object of the ceremony was to cure him of a loathsome disease from which he was suffering (To-bu-káw). The preparatory ceremonies were described as being of the same character as those which take place in the ordinary pig sacrifice for the war spirit, namely, the offering of the betel-nub tribute, the solemn invocation of the war spirits and supplication for the recovery of the officiant’s son, the sacred dance performed by the warrior priests, and the offering of betel nut to the soul of the slave that it might harbor no ill will against the participants in the ceremony.

The slave, the narrator informed me, was left unmolested, being entertained by companions of his age until the moment for the sacrifice arrived, when he was seized and quickly bound to a tree. The warrior priest, who was the father of the sick one, then shouted out in a loud voice to his war spirits asking them to accept the blood of this human creature, and without further ado planted his dagger in the slave’s breast. Several others, among whom my informant was one, followed suit. The victim died almost instantly. Then each one of the warrior priests inserted a crocodile tooth from his neck collar(Ta-ti-hán) into one of the wounds and they became, as the narrator put it, tagbusauán; that is, filled with the blood spirit. The reader is left to imagine the scene that must have followed.

Human sacrifice takes place in other forms, according to universal report. Thus one hears now and then that a warrior chief had his young son kill a slave or a captive in order to receive the spirit of bravery through the power of a war deity, who would impart to him the desire to perform feats of valor. Three warrior chiefs informed me personally that they had done this in order to accustom their young sons to the sight of blood and to impart to them the spirit of courage. I have no doubt whatsoever of the truth of their statements, as they were made in a matter-of-fact, straightforward way, as if the affair were a most natural occurrence. Accounts of such performances may be overheard when Manóbos speak among themselves.

There is also another way in which human lives are sacrificed, but it partakes less of ceremonial character than the two previous methods. I was given the names of several warrior chiefs who had practiced it. The following are the details: If the warriors have been lucky enough to kill an enemy during a fray and at the same time to secure human booty in the form of captives, they are said on occasions to turn one or more of these same captives over to their less successful friends in order that the latter may sate their bloody thirst and feel the full jubilation of the victory. I was informed that the victims are dragged out into the near-by forest, speared to death or stabbed, and thrust with broken bones into a narrow round hole. That this is true I have every reason to believe, for I heard these reports under circumstances of a convincing nature. Furthermore, such proceedings would be highly typical of Manóbo character and would probably occur among any people that valued human life so lightly and that cherished revenge so dearly. What could be more natural and more pleasing in the exultation of victory and in the wildness of its orgies than to deliver a captive, probably a mortal enemy, to an unsuccessful friend or relative that he too might glut his vengeance and fill his heart with the full joy of victory?

SOURCE: THE MANÓBOS OF MINDANÁO, John M. Garvan, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN LIBRARIES, 1931

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.