The Pangasinan people, also known as Pangasinense, are an ethnolinguistic group native to the Philippines. They are the tenth largest ethnolinguistic group in the country. They live mainly in their native province of Pangasinan and the adjacent provinces of La Union and Tarlac, as well as Benguet, Nueva Ecija, Zambales, and Nueva Vizcaya. The name Pangasinan means “land of salt” or “place of salt-making”. It is derived from asin, the word for “salt” in Pangasinan.

The province of Pangasinan has a rich and varied folk literature. An example of this is the Aligando, probably the longest local folksong at 563 lines (excluding four quatrains). It is also considered an original Christmas carol, and takes about an hour and a half to perform. Other examples of this ancient oral tradition include 631 proverbs, 465 riddles and puzzles, numerous myths, legends, tales of supernatural creatures, and love songs known as petek. The storytellers, known as tumatagaumen, wove tales for every season.

It should be noted that the information presented in this article comes from historical sources. They may represent only a small area of Pangasinan and should not be considered part of the lives for modern day Pangasinense.

Sixteenth-century Pangasinan

Sixteenth-century Pangasinan was the coast of Lingayen Gulf from Bolinao (Zambales) to Balaoan (La Union), and the delta of the Agno River, where the largest settlement—Binalatongan (San Carlos) with some two thousand houses—was only 20 kilometers inland. Bolinao was a port of call for Chinese junks: when Chinese-speaking Father Bartolome Martinez was shipwrecked on the coast nearby, he was able to baptize twenty Chinese traders he found there. This direct China trade was reflected in the Pangasinan use of porcelain jars for wine consecrated in religious ceremonies, and a Spanish complaint that not only chiefs but even ordinary people were wearing Chinese silks and cotton. It was presumably the proximity of the Zambales mountains which caused Miguel de Loarca to think the people of Pangasinan used the same language and costume as the Zambals, but were “more intelligent” due to their contact with Chinese, Japanese, and Bornean merchants. Agoo (La Union) was an emporium for the exchange of Igorot gold, which the Spaniards called “Port of Japan” because Salcedo found several Japanese ships there. Deerskins and civet were also objects of their trade.

Pangasinans were also a warlike people who were long known for their resistance to Spanish conquest. Sixteenth-century accounts regularly referred to them as either unconquered or rebellious. Tagarri was a war dance—or cockfight—dakep meant to take captives, and ngayaw was “to go out looking for anybody they wanted to kill.” Pangasinans themselves were subject to attack by Igorots, Zambals, and Negritos, but were able to defend their overland trade routes, and to take Zambal slaves for sale to Chinese.

Pangasinan culture appears to have been the same as that of Luzon groups to the south. Rice was grown in both swiddens and pond fields, where it was planted either by broadcasting or by transplanting seedlings from a seedbed. One manload of harvested palay—ten bundles (betek) of five smaller bundles (tanay)—was reckoned as one G-string (san be-el), presumably because it could be tied with one. Men practiced circumcision (galsim) or supercision (segat), wore G-strings, and blackened their teeth. They considered undecorated teeth ugly. Shamans were old women and the ceremonies they performed were maganito. Mourning rites required a human death, and there was an unusually strict sanction against adultery: both adulterers were buried alive. After colonial authority made this punishment impractical, a certain Chief Lomboy once killed his own sister for this crime. There was evidently the usual three-class social structure, with ruling chiefs being called anakbarma; their supporters, timawa.

Deities, Idols, and Folkloric Beings of the Pangasinense

Ama-Gaolay: the supreme deity; simply referred as Ama, the ruler of others, and the creator of mankind; sees everything through his aerial abode; father of Agueo and Bulan.

Agueo: The morose and taciturn sun god who is obedient to his father, Ama; lives in a palace of light.

Bulan: The merry and mischievous moon god, whose dim palace was the source of the perpetual light which became the stars; guides the ways of thieves.

Apolaqui: a war god;also called Apolaki, his name was later used to refer to the god of Christian converts.

When the first friars went to Mangaldan, Pangasinan, in 1588, they found the people there making regular business trips to the mountains, and worshipping a mountain god called Apo Laki.

Isabelo de los Reyes re-wrote the following passage from a Spanish report, “The entry of the religious into Pangasinan”, dated at Magaldan, a village of Pangasinan, November 8, 1618. It was said that two locals had seen Apolaki where he relayed the following message to them.

“I weep to see the completion of what I expected for many years, namely that you would welcome some foreigners with white teeth and hooded heads, who would implant amidst your houses crossed poles (crosses) to torment me all the more. I am leaving you to seek people who will follow me, for you have abandoned me, your ancient lord, for foreigners.”

Anagaoely: The Pangasinans worshipped an idol who they said were Anagaoley. They offered them oils, unguents, and other aromatic objects; and, if they asked, they sacrificed in its honor slaves or pigs.

Maganito: The name was used for the priests of the early Pangasinanes.

Aniani is the Pangasinense word for ghost, while Bambanig and Pugot are the name of tree deities, the counterpart of what is known in Tagalog as Kapre. The Baras is a forest-dwelling demon who steals women in Pangasinan.The Bantay is an old man living in a large tree. He turns into a great big white rooster and is said to grow smaller then bigger. It can be seen on a new moon, at night, or when there is a light shower.

Pregnant women avoid sleeping near the window at night, as to do so exposes them to the danger of their foetus being stolen by the evil spirits. Miscarriages are invariably attributed to this.

Pasatsat is an urban legend. It is said to be the ghost of a dead person who died in a tragic way, especially those who died in Japanese Era (World War II). This kind of ghost usually shows to passersby in a solitary paths in the forest or even in cities. In order for the ghost to stop haunting, someone should stab the coffin or the reed mat where the body of this ghost was buried. It will show no sign of the body but a putrid flesh can be smelled.

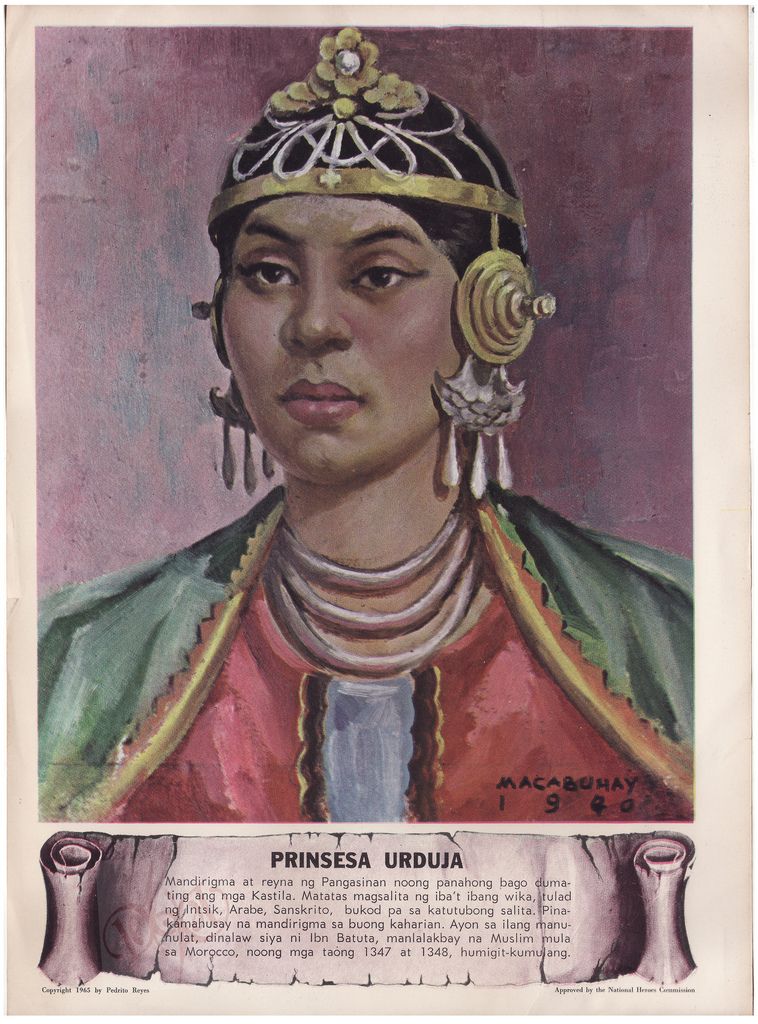

Urduja was a legendary warrior princess recorded in the travel accounts of Ibn Battuta (1304 – possibly 1368 or 1377 CE). She was described to be a princess of Kaylukari in the land of Tawalisi. In the late 19th Century, Jose Rizal, national hero of the Philippines, speculated that the land of Tawalisi was in the area of the northern part of the Philippines, based on his calculation of the time and distance of travel Ibn Battuta took to sail to China from Tawalisi. In 1916, Austin Craig, an American historian of the University of the Philippines, in “The Particulars of the Philippines Pre-Spanish Past”, traced the land of Tawalisi and Princess Urduja to Pangasinan. In the province of Pangasinan, the governor’s residence in Lingayen is named “Urduja House”. A statue of Princess Urduja stands at the Hundred Islands National Park in Pangasinan. Philippine school textbooks used to include Princess Urduja in the list of great Filipinos. The subject remains a topic of debate as many also believe that Urduja was a fabrication by Battuta, or that the land of Tawalisi was not in the Philippines.

MYTH: The Sun, the Moon, and the Stars

There was once a powerful god called Ama (father), the father and ruler of all others, and the creator of man. He had a wonderful aerial abode from which he could see everything. Of all his sons, Agueo (sun, day) and Bulan (moon) were his two favorites, and to these he gave each a fiery palace. In accordance with the wish of their father, Agueo and Bulan daily passed across the earth side by side, and together they furnished light to mankind. Now, Agueo was of a morose and taciturn disposition, but he was always very obedient to his father. Bulan, on the other hand, was merry and full of mischief.

Once, when they were near the end of their day’s labor they saw thieves on the earth below, wishing that it were night so that they might proceed with their unlawful business. Bulan, who was one of their kind, urged Agueo to be quick, so that the earth might soon be left in darkness. As Agueo obstinately refused to be hurried, a quarrel ensued between the two brothers. Their father, who had been watching the two boys and had heard all that passed between them, became very angry with the mischievous Bulan; and, in his wrath, he seized an enormous rock, and hurled it whistling through the air. The rock struck the palace of Bulan, and was broken into thousand pieces, which received perpetual light from contact with the fiery palace. These may still be seen in the heavens, and they are called Bituen (stars). Bulan was forbidden to travel with Agueo, but was commanded to light the ways of thieves henceforth with his much-dimmed fiery palace.

MYTH: Legend of Hundred Islands

Centuries ago before the coming of the Spaniards to the Philippines, there was a brave rajah who ruled over the people of Alaminos—Rajah Masubeg. He had several hundred warriors to guard his kingdom, led by his son Datu Mabiskeg. The little kingdom enjoyed peace and prosperity, unmolested by its neighbors.

But one day a report came that an invading force was coming from across the sea. The rajah called a council of war among his chieftains. They decided to meet the enemy at sea. The enemy must not be allowed to land. One hundred of the bravest warriors were summoned. They were placed in ten large bancas, armed to the teeth. Datu Mabiskeg, in the lead banca, commanded the task force.

The two forces were soon locked in mortal combat. Furious hand-to-hand fighting broke out on the boats and raged until the sun sank in the west and darkness covered the sea.

When morning came none of the hundred warriors returned alive. The enemy was nowhere to be seen; they had been annihilated, and so were the one hundred warriors led by the intrepid son. While the kingdom celebrated the victory, the old rajah mourned for his son.

A week later, when the townspeople woke up in the morning and looked toward the sea, a wonderful sight met their eyes. Where before there had been an empty expanse of water as far as the eye could see, now there were many tiny islands dotting the sea line. There were about a hundred of these islets. Some were shaped like overturned bancas; others looked like bodies of dead men floating in the sea. These, the people of Alaminos believed, were the one hundred warriors who had given up their lives in defense of their homes. The gods had immortalized them in the form of islands so that they might watch over their native land forever.

‘Witchcraft’ of the Pangasinense

The Pangasinense name for witch is bawanen. His craft may perhaps be best understood and appreciated by an illustration of himself at work. A boy which will be referred to as Bunoy for this purpose came out of their schoolroom during recess and went to play under the acacia tree in the school premise. A whip of wind felled him and he landed on the ground on his buttocks. Since then, he was never the same again. He always felt uneasy, discomfited and restless, as though something was eating him. His superstitious mother referred the matter to a bawanen who performed a ritual involving a knife. Amidst incantation and prayer, the knife was placed at the back of the standing boy. If it didn’t stick and fall, it means that no evil spell was cast upon him.

But the knife stuck like a magnet and the bawanen divulged to Bunoy’s mother that an evil spell had been cast upon her son. Whereupon, the bawanen tried to establish communication with whoever had cast the evil spell and it was learned that an encantada, who had made the acacia tree her abode in guarding a fortune buried somewhere in its premises, did it.

The motive behind it all also came to light. The encantada wanted to unburden itself of the task of guarding the fortune and is, therefore, prepared to give it away to a chosen recipient and Bunoy happened to be it. If Bunoy’s mother was willing, her son would get the fortune.

But fearful that it was her son’s life which vouched for the fortune, Bunoy’s mother declined the encantada’s offer. The bawanen conveyed this decision to the encantada, adding that she’d rather choose another person to give it to. It was in this manner that the boy Bunoy was freed of the spell and he became well, thanks to a job well done by the bawanen.

It should be understood that there are characters that can cast an evil spell aside from the encantada, and it may be another witch. The witch whose job it is to undo the spell cast by a fellow witch is called by the Pangasinense as espiritista.

Banbano refers to many things connected with sorcery. It could be the supernatural ailment which finds no cure in medical science. Or it could also be the “evil eye” or “death look” an ailment cast by magical eyes. Children are most vulnerable to this. It makes them uneasy, restless, vomit, cold sweat and have fever. Usog is the Tagalog term for it, and the one who casts it is called manangibanbano. Its cure can be effected by the manangibanbano’s saliva rubbed on the forehead or feet of the afflicted child.

Black magic is the manananem’s forte, as had been proved and attested by a fish vendor’s sad experience. There was a woman who offered to buy one of her dalag (mud-fish). Because the offer was low and would mean losses on her part to accept it, she decided to reject it. After the passage of a day, she felt something irritating in her stomach. Days later, the feeling became more definite: it was now something live and moving. When it reached the point that she could bear it no longer, she consulted her ailment to a doctor. They operated on her stomach and extracted a live mudfish, a case that bewildered the doctors who performed the operation no end.

from Creatures of Midnight (Maximo Ramos)

SOURCES:

Pangasinan Folk Literature, Perla S. Nelmida, (Ph.D. dissertation, U.P., 1982).

The Lowland Cultural Community of Pangasinan, National Commission for Culture and the Arts, https://ncca.gov.ph/

Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society, William Henry Scott, Ateneo Press (1994)

Philippine Folk Literature: An Anthology, Eugenio, D. L. University of the Philippines Press (2007)

Witchcraft, Filipino Style, Nid Anima, Omar Publications (1978)

Creatures of Midnight, Maximo Ramos, Phoenix Publishing, (1990)

DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology), Ferdinand Blumentritt, High Banks Entertainment Ltd. (2021)

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.