According to the writings of John Garvan in his early 1900’s memoir in the New York Academy of Sciences, the Mandaya is “probably the greatest and best tribe in Eastern Mindanao.”

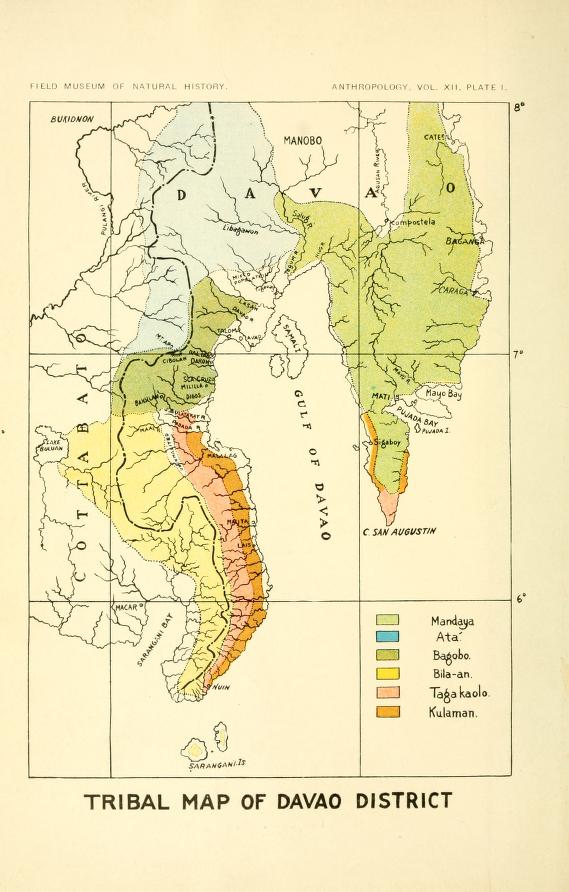

The contents of this article have been taken from the 1913 paper THE WILD TRIBES OF DAVAO DISTRICT, MINDANAO by FAY-COOPER COLE and may not accurately represent the beliefs of the modern Mandaya. Further, regional beliefs among the Mandaya might not be accurately reflected in this report, although more recent studies seem to confirm much of what has been reported, particularly the mythology and religion. This report appears to have been conducted in the Mayo District, with references to the Mandaya of Cateel, Mandaya of the Tagum river valley, and the Mandaya of the Pacific Coast.

Modern scholars have identified five principal groups of Mandaya: the Mansaka or those who live in the mountain clearings; the Manwaga or those who lived in the forested mountain areas; the Pagsupan or those who make a living in the swampy banks of the Tagum and Hijo rivers; the Managusan or those who live near the water; and the Divavaogan who are found in the southern and western parts of the Compostela. According to online articles over the last decade, many of the traditional Mandaya practices in the following report appear to be disappearing.

In general, Mandaya beliefs revolve around nature spirits (diwata), both good and bad. In contrast to the Christian belief that sets evil as absolute archenemy to one’s faith and morality, the Mandaya believe that evil spirits can be appeased and made amicable. This appeasement the Mandaya do through rituals, offerings and sacrifices. The Mandaya embrace evil if it meant making it good.

Indeed, in the Mandaya worldview and tradition, God is the source of both good and evil. The ultimate and absolute deity for the Mandaya is an infinite reality, spread throughout the immensity of the world, who designed and governs the order of the universe, from the cycle of the sun, the moon, the tide — everything. This God the Mandaya calls by the name Magbabaya, literally meaning the “Governor.”

For the purpose of this article the term “tribe” has been replaced with “ethnic group.”

In this report, the ballyan (priestess) directs the religious observances of the ethnic group. Their mysterious powers give them great influence among their fellows but, nevertheless, they are subservient to the local ruler.

The ethnic group is divided into many small groups, each of which is governed by a bagani. To reach this coveted position (as recorded in 1913) a man must have distinguished himself as a warrior and have killed at least ten persons with his own hand. The victims need not be killed in warfare and may be of any sex or age so long as they come from a hostile village. When the required number of lives has been taken, the aspirant appeals to the neighboring bagani for the right to be numbered in their select company. They will assemble to partake of a feast prepared by the candidate and then solemnly discuss the merits of his case. The petition may be disregarded entirely, or it may be decided that the exploits related are sufficient only to allow the warrior to be known as a half bagani. In this case he may wear trousers of red cloth, but if he is granted the full title he is permitted to don a blood-red suit and to wear a turban of the same hue. This distinction is eagerly sought by the more vigorous men of the ethnic group and, as a result, many lives are taken each year.

_______________________________________

In order to enter into a full understanding of the social, economic, and aesthetic life we must have some knowledge of the mythology and religious beliefs, for these pervade every activity.

MANDAYA MYTHS of the SUN, MOON & STARS

Several stories accounting for natural phenomena and the origin of the ethnic group were heard. One of these relates that the sun and moon were married and lived happily together until many children had been born to them. At last they quarreled and the moon ran away from her husband who has since been pursuing her through the heavens. After the separation of their parents the children died, and the moon gathering up their bodies cut them into small pieces and threw them into space. Those fragments which fell into water became fish, those which fell on land were converted into snakes and animals, while “those which fell upward” remained in the sky as stars.

A somewhat different version of this tale agrees that the quarrel and subsequent chase occurred, but denies that the children died and were cut up. It states that it is true that the offspring were animals, but they were so from the time of their birth. One of these children is a giant crab named tambanokaua who lives in the sea. When he moves about he causes the tides and high waves; when he opens his eyes lightning appears. For some unknown reason this animal frequently seeks to devour his mother, the moon, and when he nearly succeeds an eclipse occurs. At such a time the people shout, beat on gongs, and in other ways try to frighten the monster so that he can not accomplish his purpose. The phases of the moon are caused by her putting on or taking off her garments. When the moon is full she is thought to be entirely naked.

According to this tale the stars had quite a different origin than that just related, “In the beginning of things there was only one great star, who was like a man in appearance. He sought to usurp the place of of the sun and the result was a conflict in which the latter was victorious. He cut his rival into small bits and scattered him over the whole sky as a woman sows rice.”

The earth was once entirely flat but was pressed up into mountains by a mythical woman, Agusanan. It has always rested on the back of a great eel whose movements cause earthquakes. Sometimes crabs or other small animals annoy him until, in his rage, he attempts to reach them, then the earth is shaken so violently that whole mountains are thrown into the sea.

A great lake exists in the sky and it is the spray from its waves which fall to the earth as rain. When angered the spirits sometimes break the banks of this lake and allow torrents of water to fall on the earth below.

According to Mr. Melbourne A. Maxey (closely connected to the Mandaya of Cateel for several years), the Mandaya of Cateel believe that many generations ago a great flood occurred which caused the death of all the inhabitants of the world except one pregnant woman. She prayed that her child might be a boy. Her prayer was answered and she gave birth to a son whose name was Uacatan. He, when he had grown up, took his mother for his wife and from this union have sprung all the Mandaya.

Quite a different account is current among the people of Mayo. From them we learn that formerly the limokon,although a bird, could talk like a man. At one time it laid two eggs, one at the mouth and one at the source of the Mayo river. These hatched and from the one at the headwaters of the river came a woman named Mag (also known as Manway), while a man named BEgenday (also known as Samay) emerged from the one near the sea. For many years the man dwelt alone on the bank of the river, but one day, being lonely and dissatisfied with his location, he started to cross the stream. While he was in deep water a long hair was swept against his legs and held him so tightly that he narrowly escaped drowning. When he succeeded in reaching the shore he examined the hair and at once determined to find its owner. After wandering many days he met the woman and induced her to be his wife. From this union came all the Mandaya.

IMAGE: by Serious Studio

A variant of this tale says that both eggs were laid up stream and that one hatched a woman, the other a snake. The snake went down the current until it arrived at the place where the sea and the river meet. There it blew up and a man emerged from its carcass. The balance of the tale is as just related. This close relationship of the limokon to the Mandaya is given as the reason why its calls are given such heed. A traveler on the trail hearing the cooing of this bird at once doubles his fist and points it in the direction from whence the sound came. If this causes the hand to point to the right side it is a sign that success will attend the journey . If, however, it points to the left, in front, or in back, the Mandaya knows that the omen bird is warning him of danger or failure, and he delays or gives up his mission (among the Mandaya of Cateel, the opposite is true). The writer (Cole) was once watching some Mandaya as they were clearing a piece of land, preparatory to the planting. They had labored about two hours when the call of the limokon was heard to the left of the owner. Without hesitation the men gathered up their tools and left the plot, explaining that it was useless for them to plant there for the limokon had warned them that rats would eat any crop they might try to grow in that spot.

The people do not make offerings to this bird, neither do they regard it as a spirit, but rather as a messenger from the spirit world. The old men were certain that anyone who molested one of these birds would die.

Another bird known as wak-wak “which looks like a crow but is larger and only calls at night” foretells ill-fortune. Sneezing is also a bad omen, particularly if it occurs at the beginning of an undertaking. Certain words, accompanied by small offerings, may be sufficient to overcome the dangers foretold by these warnings. It is also possible to thwart the designs of ill-disposed spirits or human enemies by wearing a sash or charm which contains bits of fungus growth, peculiarly shaped stones, or the root of a plant called gam (the use of these magic sashes, known as anting-anting, is widespread throughout the southern Philippines both with the pagan and Mohammedan ethnic groups). These charms not only ward off ill-fortune and sickness, but give positive aid in battle and keep the dogs on the trail of the game.

There is in each community one or more persons, generally women, who are known as ballyan. These priestesses, or mediums, are versed in all the ceremonies and dances which the ancestors have found effectual in overcoming evil influences, and in retaining the favor of the spirits. They, better than all others, understand the omens, and often through them the higher beings make known their desires. So far as could be learned the ballyan is not at any time possessed, but when in a trance sees and converses with the most powerful spirits as well as with the shades of the departed. This power to communicate with supernatural beings and to control the forces of nature, is not voluntarily sought by the future ballyan, but comes to the candidate either through one already occupying such a position or by her being unexpectedly seized with a fainting or trembling fit, in which condition she finds that she is able to communicate with the inhabitants of the spirit world. Having been thus chosen she at once becomes the pupil of some experienced ballyan from whom she learns all the secrets of the profession and the details of ceremonies to be made.

At the time of planting or reaping, at a birth or death, when a great celebration is held, or when the spirits are to be invoked for the cure of the sick, one or more of these women take charge of the ceremonies and for the time being are the religious heads of the community. At such a time the ballyan wears a blood-red waist,but on other occasions her dress is the same as that of the other women, and her life does not differ from their’s in any respect. ( PEDRO ROSELL, writing in 1885, says that the ballyan then dressed entirely in red. BLAIR and ROBERTSON, Vol. XLIII, p. 217)

When about to converse with the spirits the ballyan places an offering before her and begins to chant and wail. A distant stare comes into her eyes, her body begins to twitch convulsively until she is shivering and trembling as if seized with the ague. In this condition she receives the messages of the spirits and under their direction conducts the ceremony.

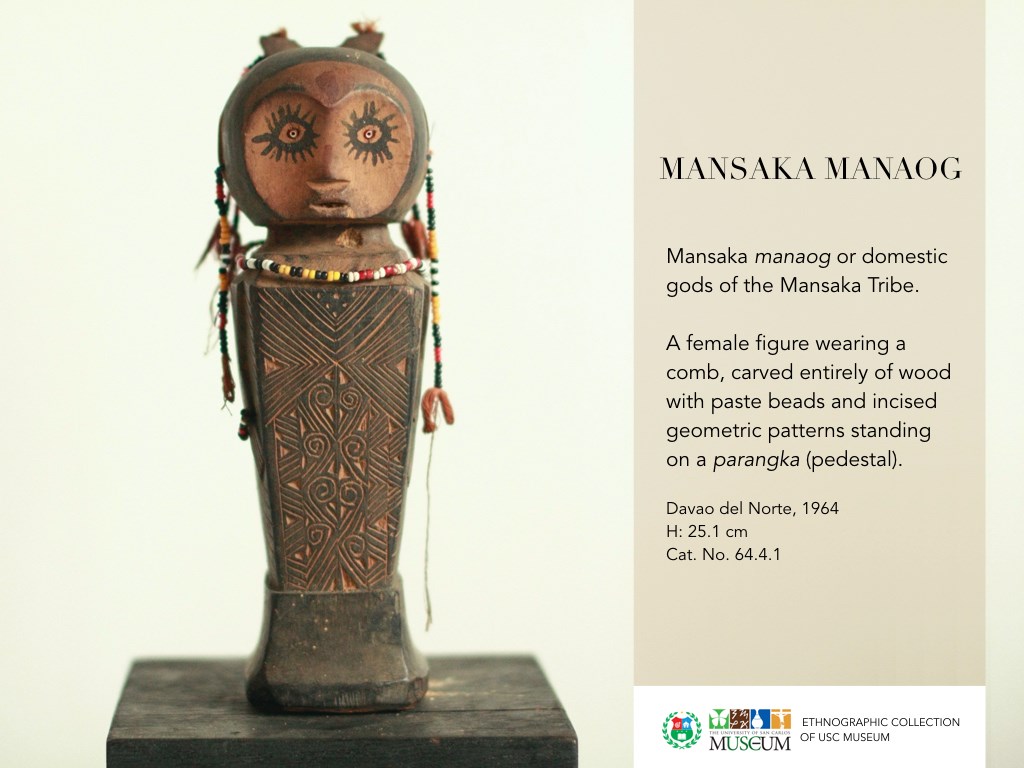

“They erect a sort of small altar on which they place the manaúgs or images of the said gods which are made of the special wood of the bayog tree, which they destine exclusively for this use. When the unfortunate hog which is to serve as a sacrifice is placed above the said altar, the chief bailana approaches with balarao or dagger in hand which she brandishes and drives into the poor animal, which will surely be grunting in spite of the gods and the religious solemnity, as it is fearful of what is going to happen to it; and leaves the victim weltering in its blood. Then immediately all the bailanas drink of the blood in order to attract the prophetic spirit to themselves and to give their auguries or the supposed inspirations of their gods. Scarcely have they drunk the blood, when they become as though possessed by an infernal spirit which agitates them and makes them tremble as does the body of a person with the ague or like one who shivers with the cold.”

PHOTO: USC Museum

SPIRITS

The following spirits are known to the ballyan of the Mayo district:

I. DIWATA. A good spirit who is besought for aid against the machinations of evil beings. The people of Mayo claim that they do not now, nor have they at any time made images of their gods, but in the vicinity of Cateel Maxey has seen wooden images called manaog, which were said to represent Diwata on earth. According to his account “the ballyan dances for three consecutive nights before the manaog, invoking his aid and also holding conversation with the spirits. This is invariably done while the others are asleep.” He further states that with the aid of Diwata the ballyan is able to foretell the future by the reading of palms. “If she should fail to read the future the first time, she dances for one night before the manaog and the following day is able to read it clearly, the Diwata having revealed the hidden meaning to her during the night conference.”

In the Mayo district palmistry is practiced by several old people who make no claim of having the aid of the spirits. Bagani Paglambayon read the palms of the writer (Cole) and one of his assistants, but all his predictions were of an exceedingly general nature and on the safe side.

Spanish writers make frequent mention of these idols, and in his reports Governor Bolton describes the image of a crocodile seen by him in the Mandaya country “which was carved of wood and painted black, was five feet long, and life-like. The people said it was the likeness of their god.” Lieutenant J. R. Youngblood, when near the headwaters of the Agusan River, saw in front of a chief’s house “a rude wooden image of a man which seemed to be treated with some religious awe and respect.” Mr. Robert F. Black, a missionary residing in Davao, writes that “the Mandaya have in their homes wooden dolls which may be idols.”

From this testimony it appears that in a part of the Mandaya territory the spirit Diwata, at least, is represented by images.

2. Asuáng. This name is applied to a class of malevolent spirits who inhabit certain trees, cliffs and streams. They delight to trouble or injure the living, and sickness is usually caused by them. For this reason, when a person falls ill, a ballyan offers a live chicken to these spirits bidding them “to take and kill this chicken in place of this man, so that he need not die.” If the patient recovers it is understood that the asuang have agreed to the exchange and the bird is released in the jungle.

There are many spirits who are known as asuang but the five most powerful are here given according to their rank, (a) Tagbanua, (b) Tagamaling, (c) Sigbinan, (d) Lumaman, (e) Bigwa. The first two are of equal importance and are only a little less powerful than Diwata. They sometimes inhabit caves but generally reside in the bud-bud (baliti) trees. The ground beneath these trees is generally free from undergrowth and thus it is known that “a spirit who keeps his yard clean resides there.” In clearing ground for a new field it sometimes becomes necessary to cut down one of these trees, but before it is disturbed an offering of betel-nut, food, and a white chicken is carried to the plot. The throat of the fowl is cut and its blood is allowed to fall in the roots of the tree. Meanwhile one of the older men calls the attention of the spirits to the offerings and begs that they be accepted in payment for the dwelling which they are about to destroy. This food is never eaten, as is customary with offerings made to other spirits. After a lapse of two or three days it is thought that the occupant of the tree has had time to move and the plot is cleared.

In former times it was the custom for a victorious war party to place the corpses of their dead, together with their weapons, at the roots of a baliti tree. The reason for this custom seems now to be lost.

3. Busau. Among the Mandaya at the north end of Davao Gulf this spirit is also known as Tuglinsau, Tagbusau, or Mandangum. He looks after the welfare of the bagani, or warriors, and is in many respects similar to Mandarangan of the Bagobo. He is described as a gigantic man who always shows his teeth and is otherwise of ferocious aspect. A warrior seeing him is at once filled with a desire to kill. By making occasional offerings of pigs and rice it is usually possible to keep him from doing injury to a settlement, but at times these gifts fail of their purpose and many people are slain by those who serve him.

4. OMAYAN, OR KALALOA NANG OMAY, is the spirit of the rice. He resides in the rice fields, and there offerings are made to him before the time of planting and reaping.

5. MUNTIANAK is the spirit of a child whose mother died while pregnant, and who for this reason was born in the ground. It wanders through the forest frightening people but seldom assailing them. The belief in a similar spirit known as Mantianak is widespread throughout the southern Philippines.

6. Magbabaya. Some informants stated that this is the name given to the first man and woman, who emerged from the limokon eggs. They are now true spirits who exercise considerable influence over worldly affairs. Other informants, including two ballyan denied any knowledge of such spirits, while still others said magbabaya is a single spirit who was made known to them at the time of the Tungud movement. Among the Bukidnon who inhabit the central portion of the island the magbabaya are the most powerful of all spirits.

7. Kalaloa. Each person has one spirit which is known by this name. If this kalaloa leaves the body it decays, but the spirit goes to Dagkotanan—“a good place, probably in the sky.” Such a spirit can return to its former haunts for a time and may aid or injure the living, but it never returns to dwell in any other form.

In addition to those just mentioned Governor Bolton gives the following list of spirits known to the Mandaya of the Tagum river valley. None of these were accepted by the people of Mayo district. According to rank they are Mangkokiman, Mongungyahn, Mibucha Andepit, Mibuohn, and Ebu—who made all people from the hairs of his head.

For the neighboring Mangwanga he gives, Likedanum as the creator and chief spirit, Dagpudanum and Macguliput as gods of agriculture, and Manamoan—a female spirit who works the soil and presides over childbirth. All of these are unknown to the Mandaya of the Pacific coast.

While in the Salug river valley Governor Bolton witnessed a most interesting ceremony which, so far as the writer (Cole) is aware, is quite unknown to the balance of the ethnic group. His quotation follows: “One religious dance contained a sleight of hand performance, considered by the people as a miracle, but the chiefs were evidently initiated. A man dressed himself as a woman, and with the gongs and drums beaten rapidly he danced, whirling round and round upon a mat until weak and dizzy, so that he had to lean on a post. For a time he appeared to be in a trance. After resting a few minutes he stalked majestically around the edge of the mat, exaggerating the lifting and placing of his feet and putting on an arrogant manner. After walking a minute or two he picked up a red handkerchief, doubled it in his hand so that the middle of the kerchief projected in a bunch above his thumb and forefinger; then he thrust this into the flame of an almaciga torch. The music started anew and he resumed his frantic dance until the flame reached his hand when he slapped it out with his left hand, and stopped dancing; then catching the kerchief by two corners he shook it out showing it untouched by fire. The daughter of Bankiaoan next went into a trance lying down and singing the message of Tagbusau and other gods to the assemblage. The singing was done in a small inclosed room, the singer slipping in and out without my seeing her.”

THE TUNGUD MOVEMENT

In 1908 a religious movement known as tungud started among the Manobo at the source of the Rio Libaganon. Soon it had spread over practically the whole southeastern portion of Mindanao, and finally reached the Mandaya of the Pacific Coast. According to Mr. J. M. Garvan, of the Philippine Bureau of Science, the movement was instigated by a Manobo named Mapakla. This man was taken ill, probably with cholera, and was left for dead by his kinsmen. Three days later he appeared among the terrified people and explained, that a powerful spirit named Magbabaya had entered his body and cured him. He further stated that the world was about to be destroyed and that only those persons who gave heed to his instructions would survive. These instructions bade all to cease planting and to kill their animals for, he said, “if they survive to the end they will eat you.” A religious house or shrine was to be built in every settlement, and was to be looked after by divinely appointed ministers. Those persons who were at first inclined to be skeptical as to the truth of the message, were soon convinced by seeing the Magbabaya enter the bodies of the ministers, causing them to perform new, frantic dances, interrupted only by trembling fits during which their eyes protruded and gave them the semblance of dead men.

By the time the tungud had reached the Mayo district it had lost most of its striking features, but was still powerful enough to cause many of the Mandaya to kill their animals and hold religious dances. The coast Moro, who at that time were restless, took advantage of the movement to further a plan to drive American planters and Christianized natives from the district. The leading Mandaya were invited to the house of the Moro pandita “to see the spirit Diwata.” During several nights the son of the pandita impersonated the spirit and appeared in the darkened room. Over his chest and forehead he had stretched thin gauze and beneath this had placed many fire-flies, which to the imaginative people made him appear superhuman. His entrance into the room was attended by a vigorous shaking of the house, caused by a younger brother stationed below. A weird dance followed and then the spirit advised the people to rise and wipe out the whole Christianized population. The Mandaya had become so impressed by the nightly appearance of Diwata that it is more than probable they would have joined the Moro in their project had not an American planter at Mayo learned of the plot. He imprisoned the leaders, thus ending a scheme which, if successful, would have given new attributes to at least one of the spirits.

(source: The Wild Tribes of the Davao District, Fay-Cooper Cole, 1913)

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.