It’s been a long time since I wrote about upcoming entertainment, but I couldn’t resist when I saw the schedule for the second season of HBO’s “FOLKLORE.” Each season of the series features the superstitions and myths of six Asian countries. Season 1 had stories from Indonesia, Japan, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia and South Korea. Season 2 visits some of the same countries but adds Taiwan and the Philippines.

Erik Matti (Seklusyon, The Aswang Chronicles, and On the Job) directs the episode titled “7 Days of Hell” that explores the folkloric beliefs surrounding Filipino sorcerers. The episode follows Lourdes (Dolly de Leon), a righteous cop desperate to save her son Eugene (Roshson Barman) from a curse set upon him by a mangkukulam.

What is a Mangkukulam?

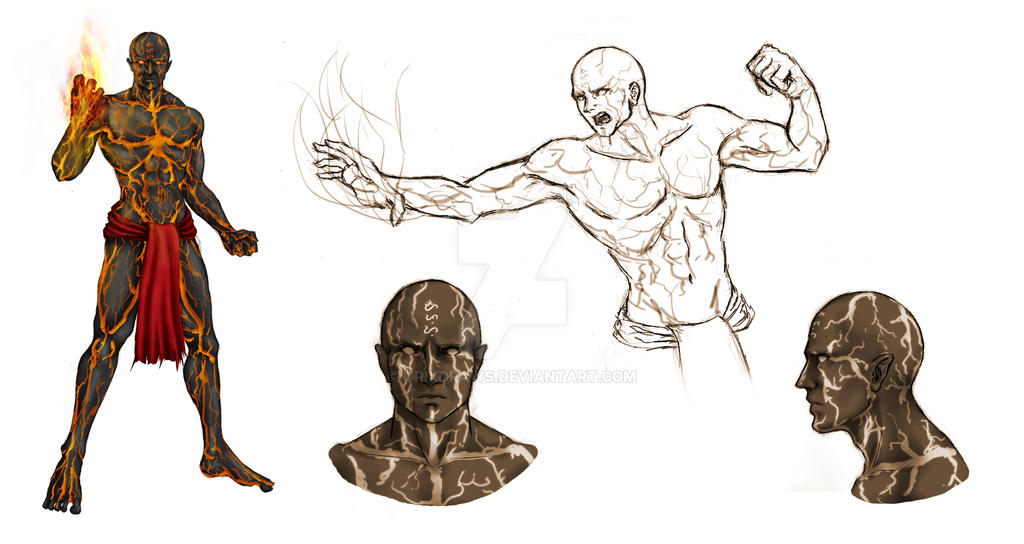

The Mangkukulam is known in modern Philippine folklore as a malady bringing ‘witch’ or ‘sorcerer.’ It is among the first documented superstitions in the Philippines, appearing in Spanish records around 1589. “The fourth was called MANCOCOLAM, whose duty it was to emit fire from himself at night, once or oftener each month. This fire could not be extinguished; nor could it be thus emitted except as the priest wallowed in the ordure and filth which falls from the houses; and he who lived in the house where the priest was wallowing in order to emit this fire from himself, fell ill and died. This office was general.”[1]

Of a more recent vintage was F. Landa Jocano’s reinvention of the Tagalog pantheon, where he is believed to have over-corrected some of the Spanish documentation. He explains that Mangkukulam may have been a malevolent deity to ancient Tagalogs. The only male agent of Sitan, he was to emit fire at night and when there was bad weather. Like his fellow agents, he could change his form to that of a healer and then induce fire at his victim’s house. If the fire were extinguished immediately, the victim would eventually die.[2]

Jose Nunez (1905) reported about the mangkukulam: By the mere wish alone, he can produce sickness in any person who has secured his ill-will. In general, the sickness that he usually deals out are most intense headaches, or aches in other parts of the body, boils or internal tumors, swellings on the head or in any other place….

Every mangkukulam has his abubut [a basket woven from rattan, which has a lid.— Robertson’s note]….When the mangkukulam plans to do any harm to any person… he goes to the quarter of the house where he always keeps his abubut and takes out the doll and pin [in it]. Then he sticks the latter in whatever part of the body of the doll he wishes. By that means… the person will be found stricken with some sort of sickness in the part of the body where the doll has been pricked.[3]

The governor and supervisor of the 1903 census for Batangas described some magical functions of the mangcuculam: The mangcuculan is a man or woman possessing the virtue of causing the sickness unto death of a person with whom he or she is displeased and this belief is so widespread that when it is rumored that a person is a mangcuculan very few will approach the same, and those who do so, do everything in their power to pleasure him or her.[4]

Anti-mangkukulam measures are quite numerous, indicating the degree of belief in the fear of these mythical beings: The only hope for one who has come under their power is for him to secure the services of a healer in possession of the necessary anting-anting. He gives his services free, for if he charged a fee the charm would not work.

Emeterio C. Cruz (1933) added that the witch doctor went to the house of the suspected mangkukulam and with the aid of a sharp bolo threatened to cut off his ears and demanded that he “go through the needle’s eye.” With this show of force he got a confession from the suspected witch, who then fell “into convulsions” and then called out: “I am through it!” Then the patient was said to rise, cured.[5]

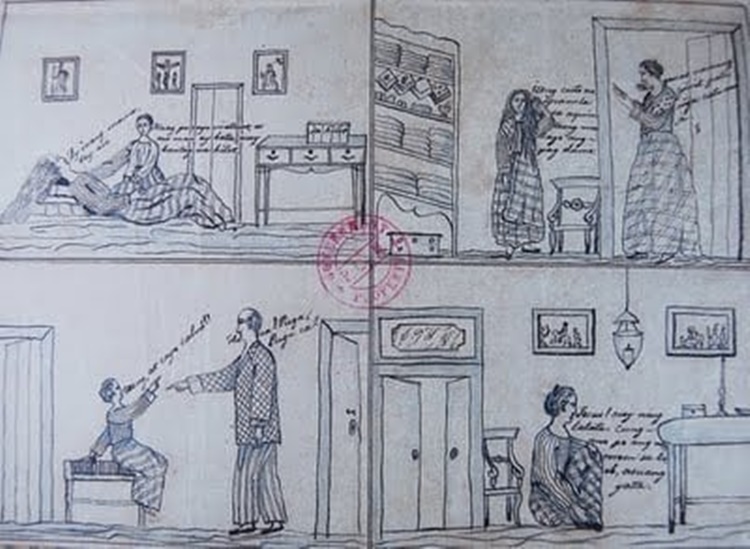

Philippine national hero, Dr. Jose Rizal, had an interest in kulam One can suppose his discourse about pangkukulam (black magic attacks) was from a desire to analyze and bring a rational light to what may have been deemed superstition.

“La Curacion de los Hechizados” (Treatment to the Bewitched) was written by Rizal during his exile in Dapitan. It consists of information regarding the difference between a Mangkukulam and Mangagaway. Rizal even drew some images of kulam victims. Perhaps because Rizal dismissed the herbolarios (healer) methods, like whipping their patients with the tail of the Pagi (Sting Ray) and incantations to expels the evil spirit that was cast by mangkukulam to torment their victims. Instead, Rizal approached kulam as a case of psychological disturbances over a cause of magic and sorcery. He believed that the curse or illness brought by the Mangagaway and Mangkukulam were only ideas that were triggered in the mind of their victims.

Rizal’s line of thinking would be later defined in medical anthropology as the “Personalistic Medical System” and is a very common approach among smaller communities, particularly those who practice forms of animism.

Adherents of personalistic medical systems believe that the causes and cures of illness are not to be found only in the natural world. Curers usually must use supernatural means to understand what is wrong with their patients and to return them to health. In the rural communities of the Philippines, this is often known as kulam, pasma, gahoy, balis, or usog. Typical causes of illness in personalistic medical systems include:

– intrusion of foreign objects into the body by supernatural means

– spirit possession, loss, or damage

– bewitching

In traditional folk medicine, the methods of determining whether a person is a victim of kulam or not is also various and caters to the respective peculiarities of the ‘witches.’ One of these is comparing similar fingers of both hands of the afflicted person. Said person is pronounced to have been bewitched if the fingers are not of the same size or shape ( I know your looking at your fingers right now).

Still another is the pressing of a magnet (bato-balani) against the patient’s thumbs. If the healer draws it away and it persists in sticking to the thumb, the patient is pronounced to be positively bewitched.

Tawas is the ritual of curing kulam. It usually consists of boiling guava leaves, herbs and roots. The person who performs the healing is often another mangkukulam. This healer would likely only be known to their clientele as a legitimate practitioner of the black art, for the function of this mangkukulam is not removed from witchcraft, though on the antidote side.

Other means of tawas involves the burning of alum (tawas), blessed palm leaves and roots on a piece of broken earthen jar. The sorcerer proceeds to interpret the shapes of the burnt alum and other ingredients, mix them in a bottle of water where a magnet (bato-balani) had been immersed. The patient is required to drink the concoction.

It is easy for people who only accept a naturalistic explanation for illness to reject the concept of the intrusion of foreign objects into the body by supernatural means. However, it is of value to keep in mind that this explanation is similar to the “germ theory” that is readily accepted by most people in the western world today. Both explanations require the belief in something that cannot be seen by most people. In both cases, there is an act of faith. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was difficult for microbiologists and physicians such as Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, and Robert Koch to convince the medical profession that bacteria and other microorganisms can cause infection and disease. It took even longer for the general public in Europe and North America to be convinced that there are harmful microscopic “germs.”

I will close this article with one last thought on the persistence of belief in sorcerers and witches. Seven years before the mangkukulam was first documented, Miguel de Loarca (1582, Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas) made the following observation, “In this land are sorcerers and witches—although there are also good physicians, who cure diseases with medicinal herbs; especially they have a remedy for every kind of poison, for there are most wonderful antidotal herbs.“ In 1892 Trinidad Pardo de Taverna would write the book “The Medicinal Plants of the Philippines” outlining these medicinal herbs and plants. Modern story tellers have become focused on the horror of folkloric beliefs, but it is equally important to showcase the balance that existed. In the case of the Mangkukulam, I would argue that the common maladies it was suspected of bringing were never a match for a skilled Albularyo (folk doctor).

“Folklore” is currently streaming on HBO Go with new episodes each week. “7 Days of Hell” is scheduled to air on Dec. 5.

SOURCES:

[1] Customs of the Tagalogs (two relations), Juan de Plasencia, O.S.F.; Manila, October 21, 1589

[2] Outline of Philippine Mythology, F. Landa Jocano, Centro Escolar University, 1969

[3] Nunez, Jose “Present Beliefs and Superstitions in Luzon, 1905.” Trans. and reprinted from El Renacimiento supplement, Dec. 9, 1905, by James A. Robertson. In Blair and Robertson, eds., The Philippine Islands, Vol. III, pp. 310-19

[4] Census (1903), p. 521.

[5] Emeterio C. Cruz, “Philippine Ogres and Fairies,” Philippine Magazine XXIX (January, 1933)

[6] The Art of Medical Anthropology: Readings, Sjaak van der Geest, Adri Rienks, Amsterdam : Het Spinhuis 1998

Additional Source:

Witchcraft, Filipino Style, Nid Anima, Omar Publishing 1978

ALSO READ: MANGGAGAWAY: Malign Magic In A Philippine Municipality

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.