Here at The Aswang Project, I have recently been receiving many requests to present more information about Philippine “witches” and “witchcraft”. I am usually left explaining that each region and ethnic group has their own beliefs, names and practices regarding such things and that there are only scattered in-depth resources available. Outside of that, we are left piecing together passing mentions in the readily available historical documents and folk tales.

The manggagaway has always fascinated me. It is one of the very few ‘witches’ and folkoric beings that has existed in documentation since the archipelago’s first chroniclers.

Juan de Plasencia authored several religious and linguistic books, most notably, the Doctrina Cristiana (Christian Doctrine), the first book ever printed in the Philippines. Among his various documentation is a list of “distinctions made among the priests of the devil”, from 1589 in the paper called “Customs of the Tagalogs”. From this: “The second they called MANGAGAUAY, or witches, who deceived by pretending to heal the sick. These priests even induced maladies by their charms, which in proportion to the strength and efficacy of the witchcraft, are capable of causing death. In this way, if they wished to kill at once they did so; or they could prolong life for a year by binding to the waist a live serpent, which was believed to be the devil, or at least his substance. This office was general throughout the land.”

FOLLOW: Charisse ‘Dadis’ Melliza Illustrations on FB

In Blumentritt’s 1895 Diccionario mitológico de Filipinas it is written: “Mangagauay. Ese nombre daban los Tagalos antiguos á cierta clase de hechiceros que mataban ó curaban con sus brebajes. (Mangagauay. The name given by the Tagalogs for certain kinds of sorcerers that killed or healed with their concoctions.)

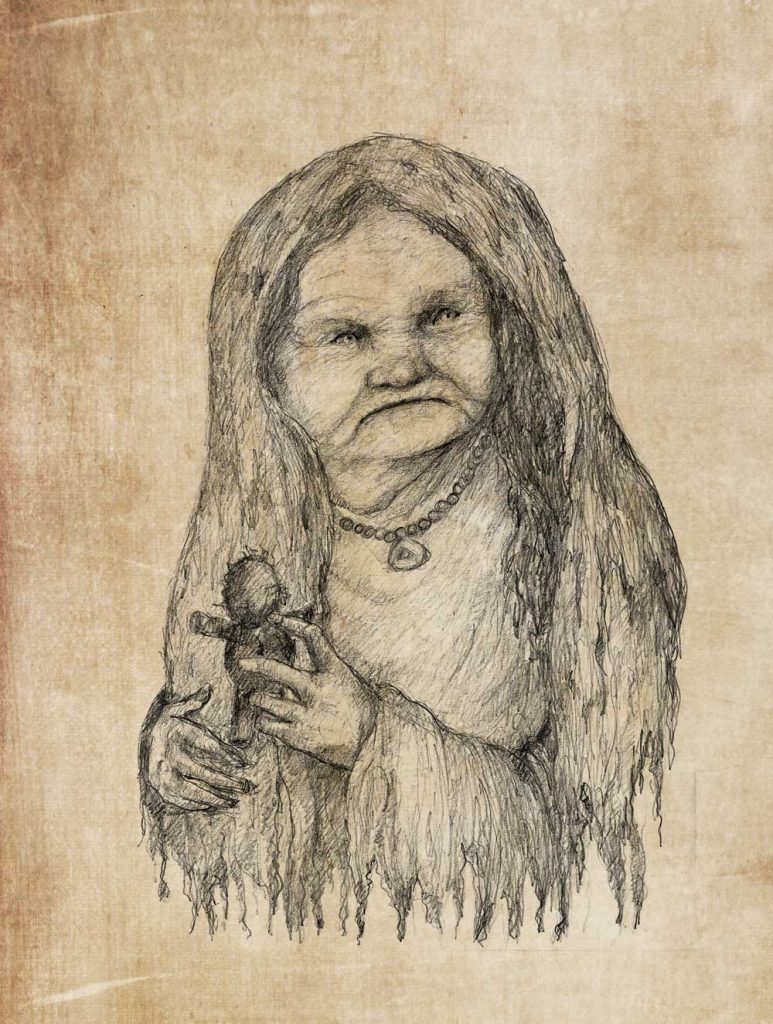

In F Landa Jocano’s 1969 Outline of Philippine Mythology he wrote: “Sitan (chief deity of the lower world – an obvious syncretization with Catholicism) was assisted by many mortal agents. The most wicked among them was Mangagauay. She was the one responsible for the occurrence of disease. She was said to possess a necklace of skulls, and her girdle was made up of several severed human hands and feet. Sometimes, she would change herself into a human being and roam about the countryside as a healer. She could induce maladies with her charms.”

I thought Nid Animo’s 1978 book, Witchcraft, Filipino Style would hold more answers on the manggagaway. Unfortunately it is only mentioned briefly, mainly saying it is the name used when there is a persistent, nagging malady in Rizal, Laguna, or Batangas.

In 1973, F. Landa Jocano published a book called Folk Medicine in a Philippine Municipality. Among other things, its purpose was to present an ethnographic picture of folk medicine among the Tagalog-speaking Filipino peasants in the municipality of Bay, Laguna Province, Philippines. Reading through it 26 years later, I am fascinated at how in-depth Jocano got when describing the supernatural elements of folk practices. The following excerpt regarding the manggagaway is invaluable in piecing together the snippets of the past to decide how this belief may have changed, or remained the same since its first documentation over four centuries ago.

THE MANGGAGAWAY by F. Landa Jocano

The manggagaway are individuals who, most people believe, possess supernatural powers to cause illness to those persons whom they wish to harm. Sometimes they can be requested to do so by a client. Such requests are made with extreme care and secrecy. There are reports of fatal incidents arising from quarrels between neighbors based on suspicions that one has requested a manggagaway to cause the illness of the other or that of his relative. No one, however, has the courage to harm the manggagaway himself, even if it is known that he inflicted the harm. Doing so can lead to further disaster. The attacker’s entire family might be harmed.

Although the manggagaway are well-known for their sorcery, they are likewise reputed for their power to heal. This is particularly true when they are the ones who have caused the illness. In other words, the manggagaway functions in both capacities—as inflictor of illness and healer of the same. This role is obviously self-contradictory. On one hand, they are feared because of their power to harm, and on the other, they are esteemed because of their skill to heal and to help people in time of need. Our informants reconcile this contradiction by saying that it is the situation which for the most part determines the manggagaway’s role—either as a dangerous man or a benevolent individual. It is also true of all persons—sometimes we are angry, other times we are not. In this alternation of moods, we play different roles.

While our informants agree that the manggagaway may be male or female, most of the known practitioners in the community are old women. No one can give us an adequate reason for this. Many have not thought about it. One informant hazards a guess: “Perhaps it has been so since the beginning of time; that is, when God punished the angels in heaven and dropped some of them as demonyo (demons). It is the demonyo who enters into a person’s body and that person becomes a manggagaway. Women have weaker control over themselves and that is why they are often victims of the demonyo.'” Many people disagree with this explanation; however, no one can offer an alternative one. At any rate, the males who possess supernatural powers usually practice other forms of sorcery like tabang and barang. They seldom do the gaway.

There are different kinds of manggagaway. They are characterized according to the manner in which they inflict harm. The most common in Bay are the palipad-hangin and the manikaan.

The palipad-hangin use the power of malign magic. The paraphernalia used are holy candles and incense. Holy candles are candles that have been blessed by the priest in church during a Mass. When a female manggagaway desires to harm someone, she takes three candles and waits until the sun sets. Dusk is chosen because, in the local concept, it is the critical part of the day. It is the end of tiring affairs for the benevolent spirits and the beginning of activities for malevolent ones. Nature is also conceived to be unstable at this time. That is why, according to our informants, most evil designs are made precisely at this time. In other words, the selection of dusk for sorcery rests, logically, on the concept of supernatural power and control over nature and man by those who know how to influence the flow of events, if only because nature’s force on human willpower is weakest at this time.

So, when dusk comes, the manggagaway enters a room where a table has been prepared as an altar. She places the incense in a platter at the center of the table and burns it. Then she prays. In doing this, she sees to it that no one witnesses her. She has to be alone lest her power will not be effective. (This is one reason why most suspected manggagaway live alone or have a room of their own if they live with their children.) As soon as the Angelus rings or, if she lives far from the poblacion, as soon as the chickens return to their roosts, she starts the ritual.

She takes the three candles and places them in the middle of the table. The candles represent the three major winds and the directions from which they come—habagat (south), amihan (north), and salatan (southwest). These winds have a strong influence on the condition of community life in Bay. Flowing as stray undercurrents to these winds are the three powerful airs that affect the physical well-being of man: hunab (evil air controlled by the lamang-lupa, or dwellers of the earth); hininga (benevolent air controlled by God and the saints); and sareno (evil air controlled by the environmental spirits, or engkanto). Hininga (literally, breath) is the most powerful of these three undercurrents because it is the life-sustaining element on earth; the two others are responsible for misfortunes and disease.

FOLLOW: Charisse ‘Dadis’ Melliza Illustrations on FB

Symbolically, the candles also represent the three major rites undergone by man in his lifetime: birth, marriage, and death. In turn, these three rites of passage are linked with the three worlds of the supernatural: the underworld, peopled by demons and evil spirits; the middle world, inhabited by spirits who are both evil and benevolent; and the upper world the domain of God Himself.

The relationships of these three sources of human and superhuman existence are symbolically embodied in each of the three candles. Because gaway is designed merely to cause discomfort and not death, the center candle—the candle of amihan (northwind), of hininga (breath), of marriage, and of the middle world—is not lighted right away. The two others on either side are lighted. The manggagaway faces the altar and prays. After doing this, she lights the center candle and puts out the two side ones. Then she prays again.

After the second prayer, she stands up and, leaning over the altar, blows the flame in the direction of the wind three times, mentioning the name of the victim with each blow. She repeats this seven times. It is believed that the wind picks up the bisa, or power, of the sorcerer and carries it to the place where the victim lives. The sareno or hunab, depending upon which time of the day the gaway is performed, receives the bisa from the powerful wind and forces this into the victim’s body through the pores of his skin, into his blood, and to the part of his body which the manggagaway wants afflicted. When the power of the manggagaway has thus penetrated the victim’s body, the person appears to be in extreme trauma, as though he is suffering from convulsions. Sometimes he develops trembling fits, a sharp, cutting headache, and a phobia against light. As one informant said: “Nasisilaw po, at ang mga mata ay nakadilat.” (FREE TRANSLATION: He cannot see light, and the eyes are dilated).

The manikaan, on the other hand, is a manggagaway who uses a doll. The doll comes in two kinds: the manikang-basahan (rag doll) and the manikang-kandila (wax doll). Our informants could not agree as to which of these is the more powerful. Some say it is the cloth doll; others declare it to be the wax one. At any rate, should the manggagaway want to use the rag doll, she performs the ritual at midday or during the early afternoon between one and two o’clock. This is the time when most people are taking their siesta or midday nap. She takes the doll and places this on top of an improvised altar. Then she prays and whispers gaway formulae, as well as the name of the intended victim to the doll. Our informants say that the magic words capture the intended victim’s double while he is asleep during siesta. The double is placed inside the doll. Then the manggagaway takes her ritual needle and whispers the magic prayer to it. She closes her eyes and forcefully sticks the needle into the doll, at the same time uttering the name of the victim. It is said that the part of the doll that the needle sticks corresponds to the part of the body in which the victim feels the pain.

If the manggagaway fails to inflict harm through this ritual, for the reason that the intended victim may not have been asleep at the time she performed it, she shifts to another technique. She ties the doll with a piece of string, usually a thread from the waistband worn by devotees when they do their religious penance for their vows, or panata, in church during the Holy Week. She hangs the doll close to a window where the wind blows. Our informants believe that the manggagaway can order the wind to carry her willpower to any place she desires. This willpower penetrates into the body of the victim. As soon as she feels that this has been accomplished, she swings the doll back and forth. As the doll swings toward her, she meets it with the needle, at the same time uttering the name of the victim. It is said that the part that the needle hits is the part of the victim’s body that suffers from pain or is maimed, should the manggagaway decide that the victim be incapacitated. If the manggagaway wants her victim to suffer still more, she does not remove the needle from the body of the doll.

Some manggagaway, as has already been mentioned, also use wax dolls. The wax is derived from candles burnt at the altar of the church in town. Our informants say that, in making the doll, the manggagaway takes extra care that no one sees her take the wax from the church. If she is seen, the doll will not have any power at all. Also, when she moulds the wax into the image of her victim, she has to take care that no one knows about it otherwise it would not be effective. As soon as the doll is finished, the manggagaway goes to church and prays. She does not bring the doll with her. She lets three weeks pass, and on the Sunday of the third week, she returns to church. Sunday is selected because this is the time when the priest performs baptisms after the Mass. With her power, she befriends one of the sponsors at a baptism scheduled to be performed on that day. She causes the newfound friend to hold the wax doll underneath the baby, so that it will be wet when the priest pours a quantity of holy water over the child’s head during the ceremony. Our informants agree that no one can notice this act because the manggagaway has the power to make things invisible. The reason why she lets another person do this for her is that she is forbidden by the nature of her work to carry out this part of the ritual herself!

As soon as the priest mentions the name of the child and the wax doll becomes wet with holy water, the soul of the infant is forced out of his body by the power of the manggagaway and is transferred to the wax doll. When the doll is returned to the manggagaway after the baptismal ceremony, the baby dies.

The performance of the gaway ritual takes place in the evening following this church visit. The manggagaway places the doll on an improvised altar. Then she prays her powerful prayers and strikes the doll with the ritual needle, at the same time saying the name of the victim. The soul of the dead child leaves the doll and enters into the body of the victim so named. Then it tortures the person’s double—-this is the reason why the victim suffers from excruciating pain or a lingering illness.

The manggagaway can make any person lose his mind. She can make a woman pregnant, as well as deliver a fish or a lizard baby. One of our informants said that the manggagaway had caused his wife to give birth to several pieces of eggs. That was what caused him to become a folk healer. When he became a powerful practitioner, he forced the manggagaway out of the community through the counterforce of his medical rituals.

During our fieldwork, no one in the community would introduce us to a suspected manggagaway. Three of our informants, whose parents-in-law were said to be manggagaway when they were alive, supplied much of the data included here. Their accounts were corroborated by other people. Most inhabitants in the community have expressed fear of the manggagaway. It is for this reason that we were not able to obtain any case biography. Nevertheless, we were informed by a number of people that becoming a manggagaway is not easy; one has to inherit the power. The power is transferred from parent to child. The inheritor is the one among the siblings who would agree to become a manggagaway. “You see,” explained one of our informants, “the manggagaway usually dies in a hard way. She struggles on her deathbed. Sometimes she remains alive for weeks, in spite of the fact that her body starts to decay. She will not pass away until one of her children, if she has several, or one of her close kin, if she has no children, promises to take over her skills and power as a manggagaway. That is why I said the manggagaway, as a skill, is inherited (mana-mana). Sometimes a best friend of a manggagaway who wants to become one can be taught and the power can be transferred to her. When this is done, the former possessor of the power will no longer be effective as a practitioner.”

No one can heal the manggagaway’s victim except those healers who possess prayers and rituals that are more powerful.

The healer we interviewed about the gaway is a specialist in this kind of illness. He said that the way to detect whether an illness is caused by the gaway or not is to feel the pulse beats. Usually, the pulse of the victim is normal at the wrist, but the palpitations at the tip of the three fingers—the hintuturo (index), the dato (middle), and the galamay (ring finger)—are sharp and rapid. Also, the back part of the hand (tig-ibabaw) is hot while the palm is cold.

If such phenomena are observed, the healer places an egg at the center of the back of the right hand. If the patient feels a deep penetrating pain, the healer is sure that the affliction is gaway. The final test is to place the egg on the forehead. If the patient becomes unconscious, then there is no doubt that the victim is under the spell of the manggagaway.

To cure the gaway and to discover who did the trick, the healer writes his most powerful prayer formulae on three pieces of paper. He drenches these with his saliva and uses them as a poultice over the forehead and the temples of the patient. Then he cross-examines the patient. “Sino anggumalaw sa iyo? Ano, tigarito o Hindi? Isigaw mo! (Who played a trick on you? Is he from here or not? You shout the name!)” If the patient hesitates, the healer scolds and threatens. It is said that the voice that comes out of the patient’s lips during the ritual seance is not his but that of the manggagaway. To check this, the healer sends someone to spy near the house of the suspected manggagaway in the community or in a nearby barrio. Often, our informants say, the manggagaway suffers as much pain as the patient. As the patient shouts in pain during the curing seance, so does the manggagaway who has inflicted the illness. This is one way of knowing who the manggagaway really is in the community.

SOURCES:

Diccionario mitológico de Filipinas, Fernando Blumentritt, 1895

La Curación de los Hechizados, Jose Rizal, 1895

Outline of Philippine Mythology, F. Landa Jocano, Centro Escolar University Research and Development Center, 1969

Witchcraft, Filipino Style, Nid Anima, OMAR Publications, 1978

Folk Medicine in a Philippine Municipality, F. Landa Jocano, PUNLAD Research House Inc., 2001

CURIOUS RIZAL WAS FASCINATED BY THE PARANORMAL by Bryan Anthony C. Paraiso,

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.