Last month, renowned historian Ambeth Ocampo warned us that “when history is taught as civics, it instills blind patriotism rather than discipline, which results from engaging with primary source research.”

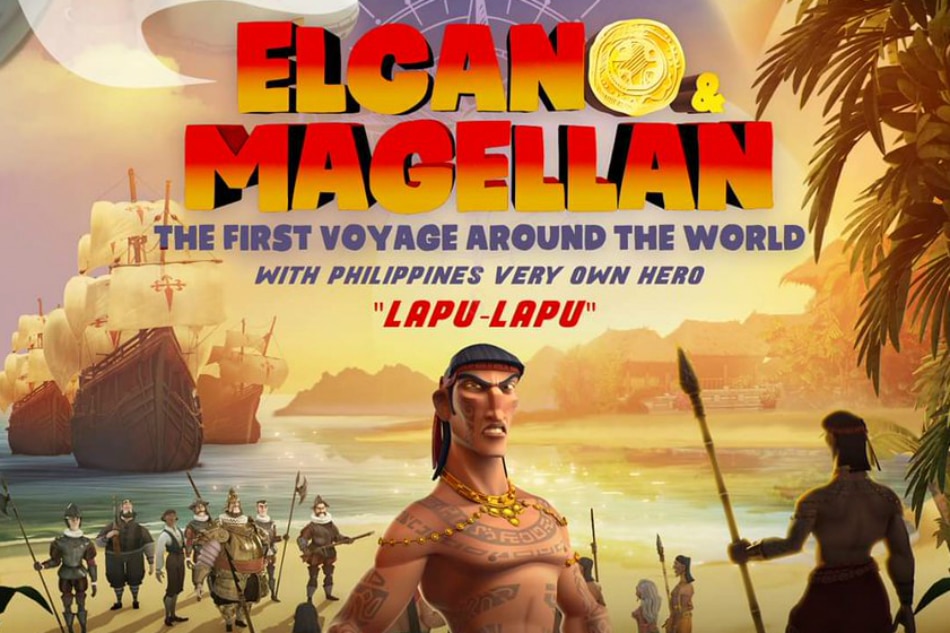

The warning was messaged in a “Looking Back” article addressing the backlash towards the animated movie “Elcano and Magellan: The First Voyage Around the World.” To generate local interest, the film distributor added to the movie poster: “With the Philippines’ very own hero Lapu-Lapu” and “Featuring the Battle of Mactan between Magellan and Lapu-Lapu.” Netizens did not take kindly to Lapu-Lapu being depicted as a villain, not a hero, his angry look contrasting sharply with the cheerful expressions of the lead characters — the “white” explorers Sebastián Elcano and Ferdinand Magellan.

Ocampo took flack for pointing out the film is the Spanish interpretation of events and is not really ‘revisionism’ while portraying what is a matter of record in the only existing primary source material. Ocampo states “Magellan was not a colonizer, he was an explorer commissioned by Spain to search for a new route to the fabled Spice Islands that would not trespass Portuguese territory. Miguel López de Legazpi was the colonizer who arrived in 1565 — four decades and four years after Magellan. There was yet no Philippines, or Filipinos, in 1521. And, going beyond the oversimplified textbook version of the Battle of Mactan, the real villain was Humabon, who feigned conversion to Christianity to forge relations with Magellan, who was then tragically enlisted in the Cebu campaign against Lapu-Lapu.”

I shared his article on The Aswang Project facebook page and in turn took flack myself for being a foreigner, curating Philippine myth and folklore, and apparently ‘supporting’ this viewpoint (I did not share my thoughts on the article at all). While I do admit that I share Ocampo’s value placed on primary source material, I differ in that I also see the cultural importance of oral tradition. I will also admit that this is where it gets tricky. To produce sound historical research, we need reliable primary sources. Records created at the same time as an event, or as close as possible to it, usually have a greater chance of being accurate than records created years later or preserved orally, especially by someone without firsthand knowledge of the event. When you are conducting research, you want to corroborate the contents of the document you have with information from other sources that have been proven or thought to be legitimate.

Notwithstanding the importance placed on accuracy, oral narratives often present variations—subtle or otherwise—each time they are told. Narrators may adjust a story to place it in context, to emphasize particular aspects of the story or to present a lesson in a new light, among other reasons. Through multiple tellings, a story is fleshed out, creating a broader, more comprehensive narrative. Should listeners ever recount the narrative elsewhere, they would likely alter it to some degree to reflect their understandings of events and to better apply the story to its present context. In some instances, precision may be crucial: both precision and contextualizing have their place in oral societies.

In contrast, written history does not present a dialogue so much as a static record of an authority’s singular recounting of a series of events. As readers, we may interpret these writings, but the writing itself remains the same. Oral narratives, on the other hand, do not have to be told exactly the same way—what is fundamental is whether or not they carry the same message.

Oral tradition is, therefore, a collective enterprise. A narrator does not generally hold singular authority over a story. The nuances evident in distinct versions of a specific history represent a broader understanding of the events and the various ways people have internalized them. Often, oral histories must be validated by the group. This stems from the principle that no one person can lay claim to an entire oral history. Narrators will also “document” the histories they tell by citing the source of their knowledge, such as a great grandparent or an elder. This is sometimes referred to as “oral footnoting.” Such collective responsibility and input maintains the accuracy of the historical record.

Prof Ivie Carbon Esteban Ph D has studied and documented how Subanen epics have been changing over time and losing stanzas at an alarming rate. The variances between the same Panay epic documented by F Landa Jocano in 1956 and then again by Alicia P. Magos 40 years later also highlight this phenomenon.

While Ambeth Ocampo makes a good point in highlighting the problems with teaching civics as history, I would argue that the real problem is the lack of critical thinking and research skills taught in the Philippine public school system. With critical thinking a student could discern the intent of written sources and compare them to the oral sources that constitute a reconnaissance of collective memory and knowledge. This kind of study would send them down a path that requires them to examine history through their ancestor’s eyes and in turn explore their own identity.

I have read most of Ocampo’s work and there is nobody better at examining historical documents and presenting them in palatable and educational findings. I do, however, find that the kind of thinking he excels at tends to under-represent the value of cultural tradition. So when there is a backlash regarding the interpretation of a national hero, such as Lapulapu, it isn’t so much of a challenge of the source material as much as it is a challenge of one’s cultural identity. Ocampo calls it “civics”, but that is likely because the cultural identity of Filipinos is elusive and ambiguous due the pressure of outside influence. Sadly, the syncretic means to which oral tradition survives is easily attacked by historians with ‘source material’. The true challenge is to understand how tradition and culture, which is comprised of behaviors, values, symbols, meaning systems, communication systems, rules, and conventions, is shaped by and in turn shapes the mind and brains of individuals in the culture.

When it comes to Lapulapu, I feel Resil B. Mojares highlights how this process could work. Below is his essay on this matter.

LAPULAPU IN FOLK TRADITION

Resil B. Mojares

University of San Carlos

HISTORY is silent on much of the story of Lapulapu, the Mactan chieftain credited with having killed Ferdinand Magellan in 1521. Where history is silent, local folk tradition has stepped in to fill the vacuum with its own order of “facts.”

Does folk tradition supply us with valid data about the hero to supplement the little that we know about him from history? Can we disengage the myth that has grown round the historical person and thus arrive at that “substratum of fact” that may underlie tradition? What new learning will such a study bring to present historical knowledge about Lapulapu? These are the questions which this paper will try to answer. For this purpose we shall carry out four operations: we shall organize and summarize existing data from the various Cebuano legends about Lapulapu; we shall try to explain some of the more problematic points in this complex of legends and determine the boundaries between folklore and history, and thus disengage one from the other; and we shall conclude by citing the value of folklore to history with reference to the case of Lapulapu.

Lapulapu in Legend

Oral tradition in Mactan yields not a single legend but a complex of legends, which is largely constituted of two “stories”: the Datu Mangal complex and the Lapulapu hero-legend.

There are many versions of the Mangal-Lapulapu story but one can discern a basic stability in these versions. The variables in the versions are relatively few in number and largely restricted to the secondary elements (or what folklorists call “allomotifs”) of the tale.

The present study, which is preliminary in nature, is based on an analysis of sixteen versions, some fragmentary and some quite full. Eleven are either from manuscript or printed sources, and five are oral versions. For a description of these versions and sources, see “Versions.”

What has survived of the Lapulapu legend consists of two joined folktales: the first, the story surrounding Datu Mangal’s petrifaction; the second, the story of Lapulapu’s preparations for his battle with Magellan, and the battle itself. Hereunder is a brief, composite version of the story:

Datu Mangal is the most powerful chieftain of Mactan Island, the center of his domain being variously placed at present-day Barrio (Bo.) Punta Engafio and Bo. Maktan. Most versions cite him as the father of Lapulapu (one version refers to him as the “uncle” and another as the hero’s “friend and right-hand man”). He is gifted with supernatural powers and is in possession of an amulet

(anting-anting), specified in one version as a mutya sa alimpulos (“pearl of the whirlpool”) and in two versions as a lana (oil). Two versions also refer to his having a flying horse.

Datu Mangal appears to be primus inter pares, acknowledged by the other Mactan chieftains, themselves gifted with superhuman abilities. Five mythical chieftains are mentioned: Bali-Alho of Bo. Maribago, who could break pestles with his bare hands; Tindak-Bukid of Bo. Marigondon, who could level a mountain with a kick; Umindig of Bo. Ibo, a champion wrestler; Sagpang-Baha (or Sampong-Baha), who could slap back an onrushing flood; and Bugto-Pasan, who could snap the sturdiest vines with his hands.

Tradition has also surrounded Mangal with a family, besides his son Lapulapu: his wife Matang Mantaunas (or Bauga; Matang-after whom Mactan is supposed to have been named-is cited in one version as Mangal’s mother) and his daughter Malingin (or Mingining). In some versions, Lapulapu is given a wife (Bulakna) and a son (Sawili).

The Mangal tale that has survived in its most complete form concerns the story of how he was turned into stone. It is told that his friend, Capitan Silyo (of Boga in some versions; of Leyte, in others), once visited Mangal to borrow his talisman for Silyo to use in a wrestling bout (or “cockfight with human gladiators,” or simply “tournament”) in Sugbo. Mangal lent the talisman on the promise that Silyo would return it on his way back from Sugbo. ‘Tan Silyo however either just forgot to return the amulet or decided to keep it for himself. A few versions have it that the violation consists of ‘Tan Silyo’s failure in noblesse oblige when, after having invited Mangal to visit his kingdom in Bogo (or Leyte), he forgot to pass by Mactan to pick up Mangal in his boat on the way back from Sugbo.

Mangal realized this when he saw ‘Tan Silyo heading away from Mactan in his boat, which was “as fast as lightning.” Forthwith, Mangal uttered a curse on Silyo. At that very moment a clap of thunder was heard and Silyo was turned into stone together with his boat (supposedly the ship-like island of Capitancillo off the northern Cebu town of Bogo today). Before ‘Tan Silyo was completely petrified, however, he also uttered a counter-curse on Mangal, who was in turn changed to stone (which is supposed to be the human rock formation now seen off Punta Engafio, Mactan Is.). According to some versions, in fact, it was not only Mangal and ‘Tan Silyo who were petrified: also transformed into stone were Matang Mantaunas (or Bauga, who is supposed to be that rock form in Tayud, Liloan); Malingin (a rock formation in Malingin Beach, Mactan Is.); and even the cook of ‘Tan Silyo, who is said to have swum to the shore, away from the cursed boat and been turned into stone when he reached the beach of Bo. Mai tom, Tabogon.

(One source has this version of the curse: Mangal’s curse returned to him and his family after it affected Silyo “because a curse that causes injury on another will also affect him who delivers it.” Another version says that Mangal was pursuing Silyo’s boat on his flying horse when he uttered the curse.) At this point, Lapulapu’s story itself begins. Mangal’s petrifaction was a gradual process that started with his feet and moved upwards. As he stood rooted in the shallows off Punta Engafio, Mangal “foresaw” the coming of the Spaniards. He then sent for Lapulapu to warn him of the impending danger, exhort him to resistance, and give him instructions. He instructed Lapulapu to fashion a pestle (alho) out of the biyanti[1] tree, and wielding it, to turnaround three times and then fling it against the coconut tree (one version says, buli ). If the pestle pierced the trunk_, then it was to be taken as an omen that the coming battle with the Spaniards would end with victory for Lapulapu’s men. Lapulapu did as he was told and the omen turned out to be good. (In some versions, in fact, the pestle pierced not only one trunk but five! )

The battle itself is dealt with cursorily, almost anticlimactically. In several versions, it simply says that the Mactan Islanders won and that Lapulapu himself killed Magellan with a blow of his alho. In the fuller versions, it is said that when Magellan and his men waded to the shore, they were attacked by various marine creatures: crabs, clams, tabugok (young octopi), ba’at (trepang)” as big as human pillows” -that encircled the feet of the Spaniards with their sticky saliva; seaweeds (lusay) that wound themselves around the intruders’ legs, “thousands and thousands of sea-urchins sticking their thorns into the fallen bodies” of the enemies. Thus bedevilled, the Spaniards were left vulnerable to Lapulapu and his men, who rushed in to give the coup de grace. This is where the story ends. However, it does not really end here: it is told to this day, and more elaborations and versions will undoubtedly be added to the story.

Problems in the Tradition

Let us now consider some of the problems in the tradition: To begin with, this narrative complex poses problems of form. What has survived is a syncretic narrative, one that has combined bits and pieces from an older body of tradition. The story of the mythical chieftains has not survived at all-if ever there was a story or stories-for what we have today are simply the nomenclature and attributes of the heroes.

The relation of the Lapulapu legend to that of Datu Mangal is problematic. H.K. Gloria (1973:200, 1975:20) believes that “Lapulapu is evidently a later accretion to the original legend.” She says that it is Datu Mangal who is “the archetypal hero, the embodiment of the heroic ideals of the people.” Indeed, an examination of the roles of the two heroes and the length of treatment accorded to each seems to support this view. We may have to wait for the collection of more versions before we can be certain about the exact relationship of the two but we shall have occasion further on to discuss the meaning embedded in this connection.

A great deal of the story is obviously mythical-which is to say, it is historically untrue, in terms of so-called “scientific” history rather than “folk history.” But is it possible to disengage the myth from this legend and arrive at some facts about Lapulapu and the Battle of Mactan that may be historically “true”? Obviously, this cannot be fully answered in the space of a short paper. We can however deal with the more prominent points and offer some preliminary conclusions.

The first question: How authentic are these stories? By “authentic” is meant: Do they really belong to the genuine oral tradition of Mactan or are they just a modem concoction of some clever individual? Our answer is that they are indeed authentic and indeed traditional in the best sense of this term. How old are these stories?

The oldest recorded version we have found can be dated at 1914. The oral versions have behind them a three-generation depth, which should bring these versions back to the mid-19th century. This is as far back as we can go in the “dating” of these texts. This is not to say that they are not much older. While the versions recorded, with their Spanish-period motifs, may have taken their present shape in the 19th century, they may have drawn from a tradition much older, perhaps as old as the middle part of the 17th century.

Our choice of this particular time-frame is suggested by Lord Raglan, a British scholar who has done work on “the hero in tradition.” Raglan (1956: 13-14) believes that without the benefit of written records, the longest that a community can remember an incident or event is 150 years. Beyond that, or even before that, the historical incident is already encrusted with myth. Statements made by Rizal in 1890, in his annotations to Morga (1962:34), and the Spanish traveler Pedro Cubero Sebastian in 1668 (in Pires 1971:30) attest to the fact that even those who had access to written records already carried a distorted view of what happened in Mactan in 1521. One can then conjecture that the folk mind may have begun to translate the historical Lapulapu into the mythical Lapulapu around this time-the mid-17th century-or perhaps even earlier.

That these stories are old, of course, simply proves that they are traditional. It does not prove that they are historical.

The next question then is: Is there anything in this legend which may be historically true, or may have an historical basis, outside of the historical fact that the battle took place?

Our contention on the matter is that there is very little of the historical in these stories, if at all.

Datu Mangal is not a historical person. He may have been, but this is something that cannot be proved. The Opon (Lapulapu City) parish records, the only reliable source for tracing the pedigrees of old Mactan inhabitants, do not go back beyond 1719, the date of the oldest item in the parish books of the Opon Catholic Church. Present-day claims of such Mactan residents as Canuto Baring (who died ca. 1962, was a popular source of Lapulapu legends and claimed direct descent from the hero) cannot therefore be substantiated.

The mention of the six mythical chieftains, with their respective “kingdoms,” is an exaggeration of the actual state of pre-Spanish polity, unless we take them to be the mythicization of petty village headmen. Antonio Pigafetta mentions only two chieftains on the island of Mactan: Lapulapu and Zula. There may have been more but, again, this cannot be proved. The ecology of Mactan Island and the nebulous state of pre-Spanish political structure argue against the kind of sophisticated polity suggested by legend.

That Lapulapu killed Magellan with a blow of the alho, again, cannot be proved. At best, it remains a possibility. Pigafetta’s account of Magellan’s death does not tally with tradition; but, of course, Pigafetta is not an entirely reliable witness. The mention of the alho as the magic weapon is also at variance with our image of Mactan society at the time of Spanish contact. H.K. Gloria (1973) theorizes that the Mactan inhabitants of Lapulapu’s time may have been orang-laut (sea-nomads, who inhabited sea and strand, fishing and collecting, a group known in various parts of the Malay world). While there may have been a tendency towards sedentary agriculture among those who settled in Mactan, they were obviously more attached to the sea than the land. This fits into our knowledge of the island’s marginal ecology and the data we have from other sources on pre-Spanish economy. It strikes us therefore as strange that an alho, an agricultural implement, should figure prominently in the Lapulapu legend. While the cultivation of rice and millet is reported of preSpanish settlements, they were cultivated in a very limited way in Cebu (and, presumably, in an even more limited way on rocky Mactan). The cultivation of these food crops, and particularly corn, became considerable only in the 19th century. (For an economic picture, see VanderMeer 1962, Hutterer 1973, and Fenner 1976.) While we cannot of course rule out the possibility that the alho, by its very “strangeness,” may have recommended itself as a magic object, there is more reason to believe that this particular feature or motif may have been formed only in a time of rapidly increasing agriculture, i.e., in the 18th and 19th centuries. It is however a possibility that the original weapon may have been a staff or a lance and may have acquired the name and image of an alho much later. But, again, we remain in the field of conjecture.

However, the possibility that there is a substratum of fact to this legend cannot be completely ignored. The most interesting part of the battle, for instance-the attack of the marine creatures (ba’at, tabugok, etc.)-may be the mythical image of an actual situation. We can deduce from Pigafetta’s account that one of the factors that contributed to Magellan’s defeat was topographical: the natural impediments of the Mactan shoreline with its tricky shallows, mangrove growths, and coral reefs, slowed down the progress of the Spanish intruders and exposed them to the arrows and lances of Lapulapu’s men. This image of the armored Castilians floundering on the treacherous, uncertain shore of Mactan may be a historical situation transmuted into myth in the story of the intruders attacked by the living creatures of the sea. Again, this is only a conjecture.

The Value of Tradition

At this point, then, what we can show for our investigation is very little. Though tradition supplements the little that we know from history, it can be said however that it does not add anything new to our knowledge of history. Here, again, we must do a double-take: the statement is not entirely correct.

And this leads us to the final question: What then does the consideration of tradition, or folklore, add to our understanding of history?

“Folk history” (as expressed, for instance, in folktales) is of a different order from “scientific history,” or “history” as it is generally conceived. The folk’s sense of history is different from our own. Though “folk memory” may not yield what we consider historical facts, it nevertheless contains historical values as important as the bare facts.

What the folk has done to Lapulapu in tradition is to enshroud him in myth. The “hero of history” has become the “hero of tradition.” And as Lord Raglan (1956) argues, the story of the hero of tradition is the story, not of real incidents in the life of a real man, but of ritual incidents in the career of a ritual personage. Even if a hero is historical, as Lapulapu was, his folk biography is not, as it is molded to fit the traditional life-pattern of the hero of myth.

That the folk has invested Lapulapu with ritual or mythical features-epic strength, the possession of a magic object, a royal pedigree, and others-is evidence of the fact that the folk considered what he did a deed of consequence and considered that he was a person whose memory should be preserved as a hero of the folk. Consider, in contrast, how the folk has edited out of mind the historical figure of the “non-hero,” Zula.

It is in this context that we should view the Lapulapu legend. There are two possibilities as to the relation of the Lapulapu legend to the Datu Mangal complex: either the Datu Mangal complex was formed to give traditional authority to the figure of Lapulapu; or, the figure of Lapulapu was attached to an old, existing Mangal complex. Either way, the folk impulse or motive is clear: it is that of giving sanction and authority in tradition to a folk hero. In this same way, we see the impulse behind the motif of the marine “helpers” in the battle: the cause of the hero being just, it is perfectly logical in the folk mind that the very forces of nature herself will come to the hero’s aid.

Folk psychology remains at work in the present-day belief that Datu Mangal and Lapulapu still live. One version has it that Mangal and Lapulapu still inhabit a Punta Engafio cave and that on moonlit nights their giant forms emerge and engage in combat over the waters to keep themselves fit to defend the island. To this day, it is reported that sailors and fishermen who pass by the Mangal “landmark” in Pun ta Engafio throw bits of food and other offerings into the water in the belief that if they fail to do so a whirlpool will appear and drag them to the bottom of the sea. During the Japanese occupation, there were islanders who placed their trust in the return of Lapulapu to free them from the invaders. [2]

G.L. Gomme (1968:40) has said: “The fact of added tradition brings out the estimate of the worth of the hero to those among whom he lived and for whom he fought.” Tradition then certifies to the great place of the hero in the popular estimation.

Indeed, tradition tells us much more about how the people view the historical event than about the event itself, and more about how they regard the historical person than about the person himself. This does not mean that in studying tradition for the purposes of history we come out with the short end of the bargain. Popular perceptions of events and individuals are as important as the events and the individuals themselves, not only for history as an academic study but, more so, for history as that living process of which we are all participants.

At one point of historical time, a man called Lapulapu performed what the people saw to be a great deed. Since then he has become a hero in tradition, and because he is a hero of tradition, he has truly become a hero of history.

[1] It is not clear as to what biyanti is. One dictionary defines by anti thus: “smooth shrub occasionally planted as ornamental which exudes a milky sap irritating to the skin, Homalanthus populneus. See John U. Wolff, A Dictionary of Cebuano Visayan (Manila, Linguistic Society of the Philippines, 1972). Buli is Cebuano for the burl palm: Coryphaelata.

[2] There are interesting sidelights to this persistence of tradition: Popular superstition has it that the figure of the Lapulapu monument in the Opon plaza, with the hero holding a bow and arrow pointed at the Opon town hall, may have caused the death of three successive town mayors. Erected in 1933, the monument was modified in 193 7 to the present one of the hero holding a pestle, in deference to popular belief (Alvez 1938, Bautista 1960).

In the Cebu Carnival of 1930, the giant alho and kuwako (pipe) of Lapulapu were put on public exhibit (“Kuwako ug alho ni Lapulapu ipasundayag sa Kamabal,” Bag-ong Kusog, 14: 36, Jan, 3, 1930, p. 24.) Antonia Baring (the daughter of Canuto Baring, the owner of these artifacts), however, said in an interview with this writer, that these were just old artifacts that were dug up and “ascribed” to the hero.

VERSIONS

1. An anonymous narrative (“Si Kapitan Silyo ug Si Datto Manggal”) said to have been first published in the Cebu periodical La Tribuna (1913). In: Nicolas Rafols, ed., “Mga Sugilanon ug Balak” (Cebu, n.d.), vol. I, pp. 68-70, an unpublished compilation of miscellaneous pieces in the Cebuano Studies Center, University of San Carlos.

2. The account of Vicente Gullas (1938). Gullas cites Canuto Baring as one of his sources. It is clear however that Gullas has novelized his account and invented fictional characters and sequences, making his book a corrupt source for folklore.

3. A casual account by Felix Sales in his Ang Sugbu sa Karaang Panahon (1935), a popular history of Cebu. See F.S. Go 1976:20-24.

4. Fernando A. Buyser’s “Kapitan Silyo ug Dato Manggal,” as rendered into verse by E. Batiancila in Bag-ong Kusog (Nov. 22 & 29, 1940) and reprinted in Buyser 1941:17- 25.

5-7. A group of legends in the “Historical Data Papers: Province of Cebu,” in the section pertaining to the towns and barrios of Mactan. The source of these legends are the public school teachers who submitted historical reports on their localities to the Department of Education in 1952-53. The original of the HDP is in The National Library (Manila); a microfilm copy of the Cebu reports is in the Cebuano Studies Center.

8. The first-person account of Canuto Baring as recorded by Augusta L. Dimataga and published in Lapulapu; The Hero and The City (Lapulapu City, 1971), unpaged. Reprinted in Cebu Today 1973 (Cebu: Provincial Tourism Council, 1973), pp. 119-120, 137.

9. The thesis of H.K. Gloria: 1975. Gloria presents what appears to be a composite version of tales she collected from various oral and printed sources. She does not however cite specific attributions.

10.11. Articles written by Rafael A. Bautista (1957, 1960, and 1962) and by D. M. Estabaya (1965). Bautista is not always clear on his sources, though it is possible that he may have drawn from Gullas (1938). He also cites a Fr. Jose A. Burgos apocryphon La Vida de Filipinas Pre-Historico (1864) as a source.

12. Oral version by Antonia Baring, 60 years old, of Bo. Maktan, as told to H.K. Gloria, Dec. 29, 1971. Published in Gloria 1973.

13. Oral version by Estanislao Mahusay, 63 years old, of Bo. Punta Engafio, as told to R.B. Mojares and L.M. Liao, April 14, 1979. Text at the Cebuano Studies Center.

14. Oral version told by Antonia Baring (see no. 12) later, to R.B. Mojares and L.M. Liao, April 14, 1979. Tape and transcription at the Cebuano Studies Center.

15. Oral version by Bayani P. Dequito, 59 years old, of Lapulapu City, as told to R.B. Mojares, April 19, 1979. Text at the Cebuano Studies Center.

16. Oral version by Maximo Sitoy, 76 years old of Cordoba, Mactan Is., as told to R.B. Mojares, April 28, 1979. Text at the Cebuano Studies Center.

SOURCES

Alvez, Primo Joel, 1938 “Si Lapulapu Bay Nagpatay sa Duha ka Presidente sa Opong?” Bag-ong Kusog, 23;2 (May 13, 1938), 27.

Bautista, Rafael A. 1957 “Lapulapu was not a Filipino.” Philippines Free Press, 48:21 (May 25, 1957), 66-67.

1960 “A Pestle for Lapulapu,” Philippines Free Press, 53:20 (May 14, 1960), 58.

1962 “A Legend of Lapulapu,” Philippines Free Press, 55:19 (May 12, 1962), 61-62.

Buyser, Fernando A. 1941 “Kapitan Silyo ug Dato Manggal,” in: Balangaw (Sugbu: no pub.), pp. 17-25. Rendered into verse by E. Batiancila; originally appeared in Bag-ong Kusog (Nov. 22 & 29, 1940).

Estabaya, D.M. 1965 “Kinsay Mga Kagikan ni Lapulapu,” Bisaya, 30:48 (Mar. 10, 1965), 22, 27.

Fenner, Bruce L. 1976 “Colonial Cebu. An Economic-Social History, 1521-1896.” Ph.D. diss., Cornell University.

Gloria, Heidi K. 1973 “The Legend of Lapulapu: An Interpretation,” Philippine Quarterly of Culture & Society, 1:3 (Sept. 1973), 200-208.

1975 “Events in Maktan from 1521 to the Beginnings of American Rule in 1900.” M.A. thesis, University of San Carlos.

Go, Fe Susan 1976″Ang Sugbu sa Karaang Panahon: An Annotated Translation of the 1935 History of Cebu.” M.A. thesis, University of San Carlos.

Gomme, George Lawrence 1968 Folklore as an Historical Science. London: Methuen & Co.

Gullas, Vicente 1938 LapuLapu; Ang Nakabuntog Kang Magellan. [Cebu, no pub., 1938 ].

Historical Data Papers, 1952-53 Historical Data Papers: Province of Cebu. Compilation of local reports from public school teachers in the Philippines, at The National Library. Microfilm copy at the Cebuano Studies Center.

Hutterer, Karl 1973 An Archaeological Picture of a Pre-Spanish Cebuano Community. Cebu: San Carlos Publications.

Pigafetta, Antonio 1969 First Voyage Around the World. Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild.

Pires, Tome, et al. 1971 Travel Accounts of the Islands (1513-1787). Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild.

Raglan, Lord 1956 The Hero; A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama. New York: Vintage Books.

Rizal, Jose, annotator. 1962 Antonio de Marga’s Historical Events of the Philippine Islands. Manila: Jose Rizal National Centennial Commission.

VanderMeer, Canute 1962 “Com on the Island of Cebu, the Philippines.” Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan.

SOURCES FOR THE INTRODUCTION:

Ocampo, Ambeth, November 13, 2019 Lapu-Lapu, Magellan and blind patriotism, Inquirer

Hansen, Erin, Oral Traditions, indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.