This Bikol tale features Prince Bantugan, a character who also appears in the Maranao Darangen. This legend also features a similar story to that faced by Bantugan in the Maranao epic of Mindanao. My first question was , “How did that happen?” Let’s explore…

The story of the Philippine archipelago is a story of movement. Movement of people, movement of language, movement of stories, and movement of culture. Over the past several years at The Aswang Project I have shared stories that tend to fit in nice tidy boxes and structured ‘pantheons.’ When I began this project, there was very little accessible information on Philippine Mythologies. The articles presented were meant to assist in understanding a particular religion at the time it was documented. As everyone finds out on their journey, Philippine Mythologies are infinitely more complex than this.

We are now in a time where there are record numbers of people passionate about Philippine Mythologies. I am starting to see a lot of very firm corrections made when people may be colouring outside the lines of documentation made at the time of colonization. Many times when I read these threads, the deviation can actually be attributed to a folk tale or myth. For instance, Amanikable was historically documented as the “idol of hunters,” yet F. Landa Jocano gathered two legends (‘Why the Baka-Bakahan Have Scales and Horns’ & ‘The Legend of the Sea Horse’) where Aminikable is the ill-tempered ruler of the sea. One is no more correct than the other, they are simply documented at different times in history and in different locations. Mythology evolves and varies. In more extreme circumstances, pantheons have been crossed. Jocano also documented the Kapampangan deity Mayari, as a Tagalog deity and daughter of Bathala (Supreme deity of the Tagalogs). It isn’t just Jocano, P.R. Villanueva documented a Tagalog myth featuring the Visayan deity of war, Sidapa, (Why the Cock Crows at Dawn) in Alamat ng mga Kayumanggi. The Tagalog creation of man myth bears a striking resemblance to the first part of the same Visayan myth. The Visayan creation of the cosmos myth is almost identical to one found in Bicol. If more fieldwork were being performed, I think we would see much more crossing of pantheons due to regional differences and migratory workers of the past. The Spanish documentation, and the work done since, is by no means extensive and inclusive of all regions and mythologies. It barely scratches the surface.

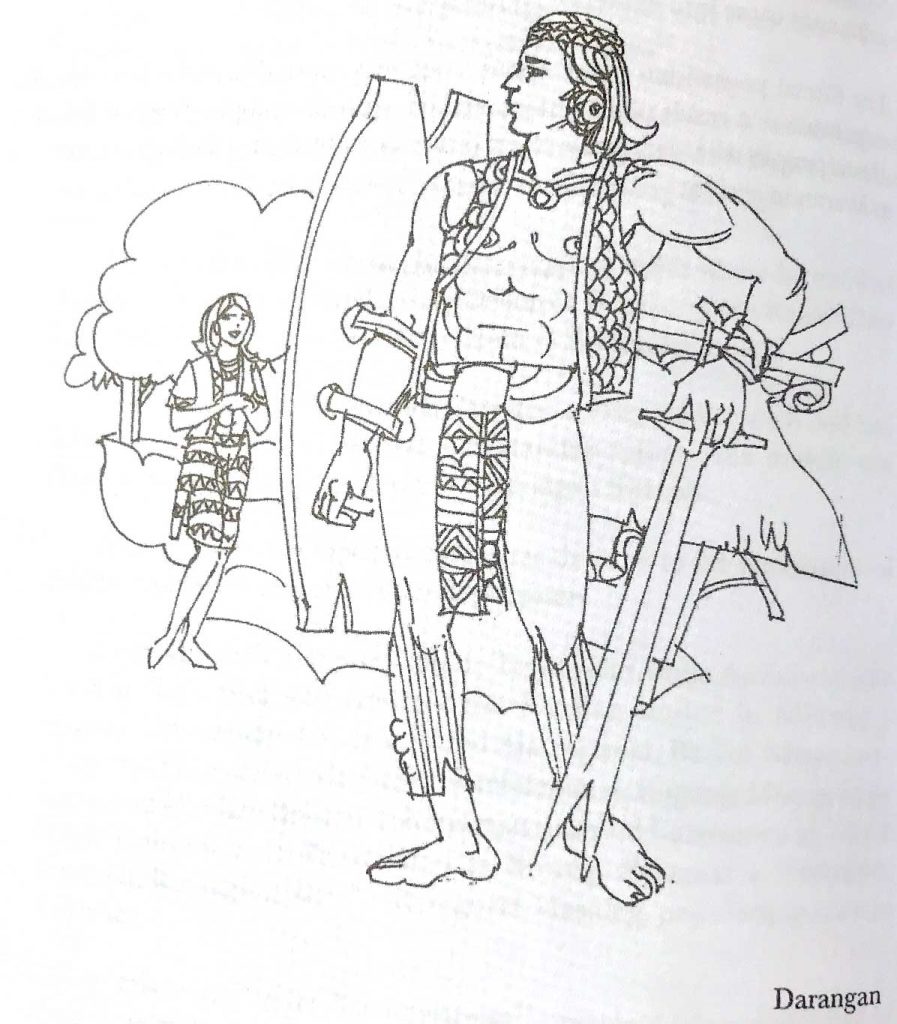

Here is another one. Bantugan is most famous for being a handsome prince in the Darangen from the Maranao people of Lake Lanao. He comes from a kingdom called Bumbaran and travels the world to save his kingdom. One of the more notable cycles of the Darangen epic deals with the exploits of the Bantugan. What may be surprising for some is that Prince Bantugan also appears in a Bikol folk story documented in 1967.

The Legend of the Shooting Star (Bikol)

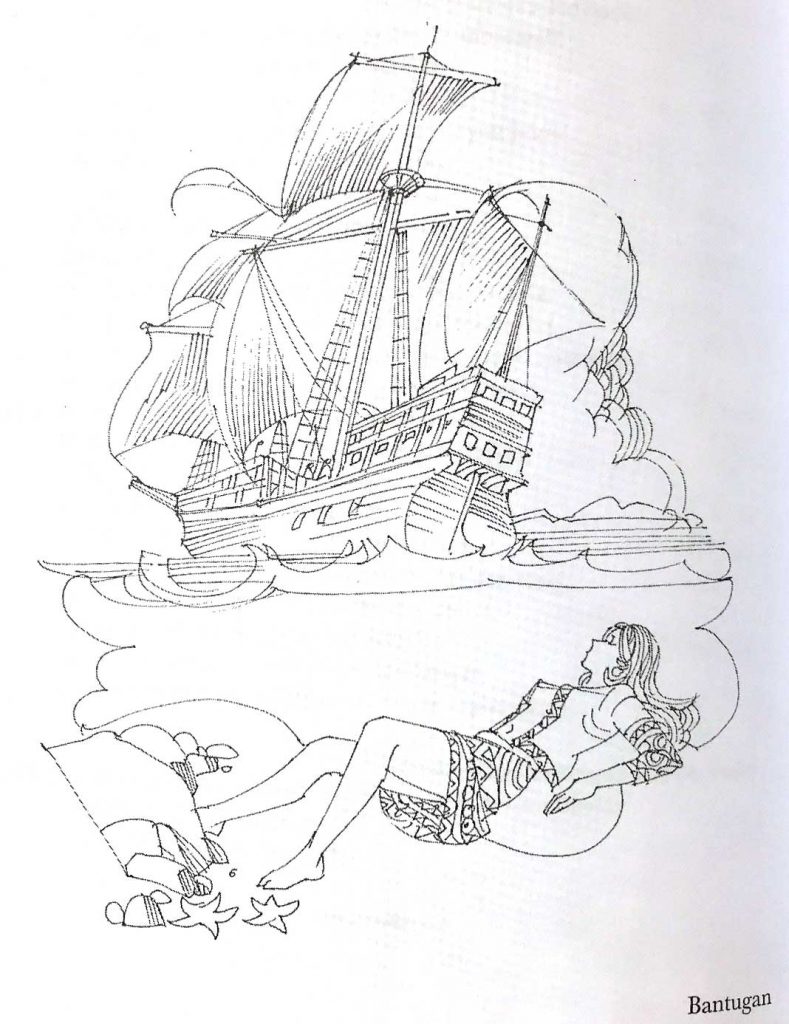

On clear nights, shooting stars are frequently seen over the town of Buhi. People believe that it is the image of the tragic Prince Bantugan who is announcing to the people of Buhi that he is still alive and is thus appearing to them to let them know that he is looking for his betrothed, the most beautiful maiden of the tribe of Acle, Bautong na Doncella.

This beautiful maiden was the muse of many poets and her beauty was the theme of Hadong Handiong, Cadugnun, and other Bicol poets. She was known not only in the Bicol region but also in other far places as seen in the fact that several places have been named after her like the mine of Doncella in Matanay, in barrio Sagrada, Familiam Buhi; another place is called Ki Doncella, located in the mountain of Bula in barrio Itagon.

Doncella’s beauty was so legendary that an encanto fell in love with her and kidnapped her. She disappeared one day and was never heard from.

Poor Prince Bantugan was desperate. He did not know where to look for her as there was no trace of the beautiful Doncella. Since he was the favorite young man of the gods from the town of Anggugurang, being the most handsome, strong, brave, and as generous as he was handsome, the god Bikol chose Bantugan to be one of his celestial messengers. Bantugan then disappeared and went to live in the Palace of the Gods in heaven. The Bicolanos believe that when they see a shooting star, it is Bantugan giving a sign that he wants to see them.

To perpetuate his memory, several places have been named after him: one is the summit of a mountain between Adiagnao, Lagonoy, and Polomoan de Caramoan of the province of Camarines Sur. Another is in Mt. Buhi towards Sagnay.

SOURCE: M.D. Coronel, Stories and Legends from Filipino Folklore (1967), p. 160. Collected by Alejo Arce of Naga City.

DARANGEN EPIC: A Little Context

The Darangen is an ancient epic song that encompasses a wealth of knowledge of the Maranao people who live in the Lake Lanao region of Mindanao. This southernmost island of the Philippine archipelago is the traditional homeland of the Maranao, one of the country’s three main Muslim groups.

Comprising 17 cycles and a total of 72,000 lines, the Darangen celebrates episodes from Maranao history and the tribulations of mythical heroes. In addition to having a compelling narrative content, the epic explores the underlying themes of life and death, courtship, love and politics through symbol, metaphor, irony and satire. The Darangen also encodes customary law, standards of social and ethical behaviour, notions of aesthetic beauty, and social values specific to the Maranao. To this day, elders refer to this time-honoured text in the administration of customary law.

Meaning literally “to narrate in song”, the Darangen existed before the Islamization of the Philippines in the fourteenth century and is part of a wider epic culture connected to early Sanskrit traditions extending through most of Mindanao. Though the Darangen has been largely transmitted orally, parts of the epic have been recorded in manuscripts using an ancient writing system based on the Arabic script.

The Darangen was originally a purely oral tradition. Its importance was first recognized by Frank Charles Laubach, an American missionary and teacher then living in the Lanao Province. He first encountered it in February 1930 on a return trip to Lanao by boat after he had attended the Manila Carnival. He was accompanied by 35 Maranao leaders, two of them sang darangen (epics) of Bantugan for the two-day journey.

After hearing parts of the Darangen, Laubach was so impressed by the “sustained beauty and dignity” of the songs that he immediately contacted Maranao people who could recite various parts of it. He transcribed them phonetically by typewriter. His best source was the nobleman Panggaga Mohammad, who also helped Laubach transcribe the epics. Laubach described Mohammad as a man who “knew more Maranao songs than any other living man.” Laubach published part of the Darangen in November 1930 in the journal Philippine Public Schools. This was the first time the oral epics have ever been recorded in print, and it was also the first instance of the Maranao language being published in the Latin script.

“When you pass by the houses of the Maranaws at night, you can hear them singing folk songs or reciting poems that are beautiful and strange. Yet on account of the absence of a Maranaw writer, Maranaw literature has remained in the dark for other people. It has become something of a tale that other Filipino tribes hear only from visitors to Lanao.”

-Frank Charles Laubach

The Ramayanas of Southeast Asia

The Story of Rama, about a prince and his long hero’s journey, is one of the world’s great epics. It began in India and spread among many countries throughout Asia. Its text is a major thread in the culture, religion, history, and literature of millions. Through its study, teachers come to understand how people lived and what they believed and valued. As the story became embedded into the culture of Southeast Asian countries, each created its own version reflecting the culture’s specific values and beliefs. As a result, there are literally hundreds of versions of the story of Rama throughout Asia, especially Southeast Asia.

Cambodia – Reamker

Java, Indonesia – Ramayana Jawa

Java, Indonesia – Ramayana Jawa

Malaysia – Hikayat Seri Rama

Myanmar (Burma) – Yama Zatdaw (Yamayana)

Thailand – Ramakien

Mindanao, Philippines – Darangen, Singkil

The Ibálong, also known as Handiong or Handyong, is a 60-stanza fragment of a Bicolano full-length folk epic of Bicol region of Philippines, based on the Indian Hindu epics Ramayana and Mahabharata. The epic is said to have been narrated in verse form by a native poet called Kadunung.

Speculation Time

All the above is to lay the ground work for some speculative guess work on how Prince Bantugan from the Maranao epic ended up in a Bikol legend. While the Ibalong is certainly the known epic of Bikol, perhaps there were other epics that have been lost to colonization and time. The Legend of the Shooting Star may be the very last fragment remaining of what could have been another epic of Bikol that shared a source to that of the Maranao’s Darangen.

This fragment may have been adapted for what was called a “moro-moro” play. The premise of these plays was described by a European traveller to Daraga, Albay in 1860. A brief description of the plot is as follows: a princess is abducted by an evil shepherd who has a serpent and lion guarding her. She uses her charms through dance to enslave the beasts. A prince eventually finds her and rescues her. The king is pleased and the prince and princess are married. ” This type of play is called Moro-moro and is a very popular form of entertainment in this region. The Bikols are a captive audience, holding their breath during tense scenes, swooning over the romantic parts and sometimes whistling in cadence to accompany the actor’s lines.”

Another possibility is that the story was transmitted through Moro raids – from captured Bicolanos who may have eventually returned. Between 1580 and 1792 there were several Moro raids against Bicolandia.

I’d love to get feedback from others over at Facebook or Instagram on how you think the story of Bantugan arrived in Bikol.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES:

Bikol Maharlika, Jose Calleja Reyes, Goodwill Trading Inc, (1992)

Muslim Raids in Bicol, 1580-1792, Francisco Mallari, S.J., Philippine Studies vol. 34, no. 3 (1986) 257–286

Darangen epic of the Maranao people of Lake Lanao, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/darangen-epic-of-the-maranao-people-of-lake-lanao-00159

Philippine Folk Literature: The Epics, Damiana Eugenio, UP Press, 4th Pressing (2018)

Outline of Philippine Mythology, F. Landa Jocano, Centro Escolar University, 1969

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.