There is something about Visayan Mythology that has always bothered me. When it comes to Cebu, Bohol, Leyte and Samar, there is almost no unique regional documentation of the ancient deities. Instead, we are left solely with the pantheon documented in Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas by Miguel de Loarca in 1582.

Modern documentation often says that Loarca used the term Yligueynes in reference to coastal Hiligaynon or Ilongo speakers (meaning Panay and Western Negros), which is true. Other historians have referred to the term Yligueynes meaning the people of the “pintados (painted ) islands” (meaning Panay, Negros, Cebu, and Bohol), which is also true. Loarca, in fact, used the term simply to refer to “people of the coast” throughout the Visayas. Through his account, Loarca introduced deities that were specific to Panay (Sidapa, Pandaque, Simuran and Siguinarugan), and Negros (Lalahon), but only one that could be considered specific to Cebu or Bohol.

“The souls of the Yligueynes, who comprise the people of Çubu, Bohol, and Bantay, go with the god called ‘Sisiburanen’, to a very high mountain in the island of Burney.”

Although he later presents Sisiburanen in a more general context which could be interpreted as a belief for all Yligueynes.

As time has passed, new deities have been introduced to the Visayan Pantheon through findings such as the Hinilawod Epic (now referred to as the Sugidanon Epic) of Panay. However, these are specific to the Bukidnon or Sulod people and should not be applied through the entire Visayas.

This is why I am excited to add Sappia as a deity in the Bohol Pantheon of Visayan Mythologies. Below you will find the myth and the history that may have brought it there.

The Rice Myth (Bohol)

From Bohol comes a story which tries to explain why rice is white. However, there is a variety of red rice which the same myth also attempts to explain.

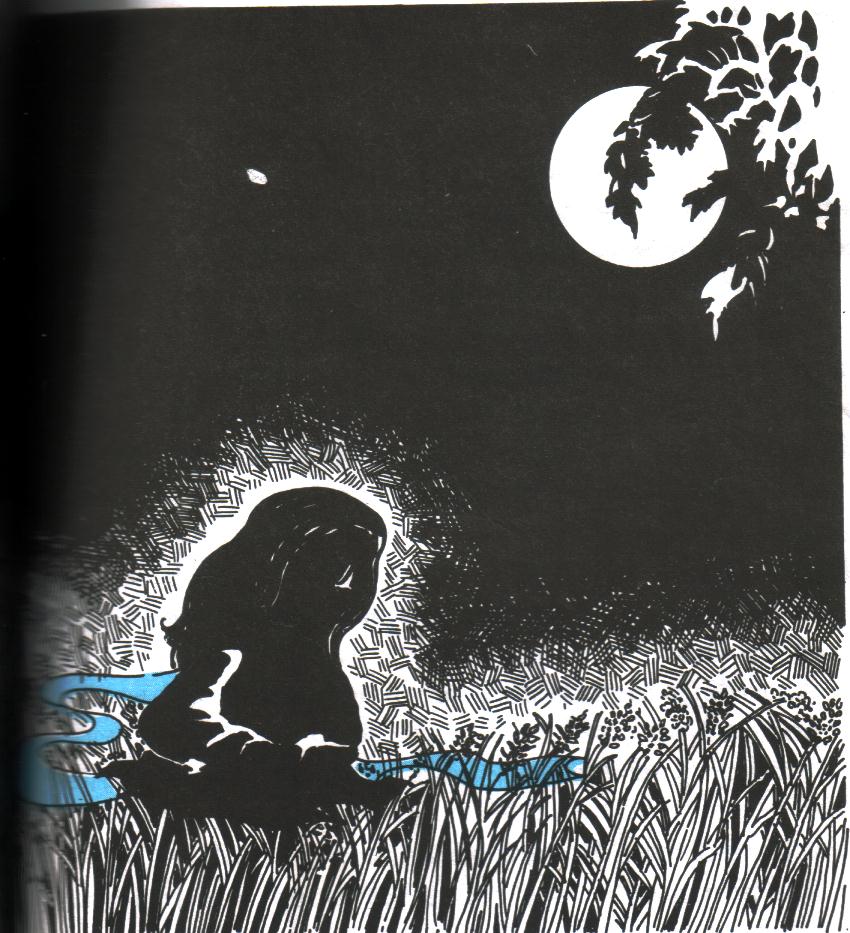

A long, long time ago, a famine gripped Bohol. The people begged Sappia, the goddess of mercy, to give them food. Sappia took pity on them and came down to earth.

All land was brown and sear. A long drought left the land parched. Only the most hardy weeds survived the long, rainless months, and already, people were dying of hunger.

Her heart welling with compassion, Sappia bared her bosom and squeezed a drop of milk into each barren ear of the weeds. She emptied one breast, and then the other, but alas! There were still a few more weeds with empty ears. She implored heaven to give her more milk, but when she pressed her breast again, blood and not milk dropped into the remaining sterile ears. Having given her all to the plants, she bent low and whispered:

“Oh, plants! Bear thou in abundance, and feed my hungry people.”

So saying, Sappia vanished from the earth. She returned to heaven where everyday she watched the useless weeds grow heavy with grain. She watched as the hungry gathered the ripened stalks.

When the people pounded the harvest, most of the grains were milky white. These came from the ears which Sappia filled with her milk. Some grains were red, and these came from those which were filled with her blood. But red or white, the people cooked the grains, found them good to eat, and best of all, these nourished them back to strength. They saved some of the seeds which they planted when the rains came soon after. The seeds gave a bountiful harvest as the first. From her heavenly home Sappia rejoiced with the people. This life-giving grain which was her gift into the famine-stricken people of Bohol is what we now know as rice.

Origin of the Myth

I knew I was familiar with this story, so I set myself to the task of trying to remember where I had seen it. It turns out that a similar tale from Northern Borneo exists:

According to a Kadazandusun (largest native group of Bumiputra in Sabah) myth, it was told that once Bambarayon (the name of the rice spirit in this myth) took pity on the human race as they had not enough food to continue their lives. Bambarayon felt sorry for them and went to heaven to ask Kinoingan (Chief God) for help. When Bambarayon returned from heaven, she started to squeeze her breast so that her milk flowed into the empty ears of rice which then began to bear white rice. Bambarayon keeps on squeezing her breast until there was no more milk left, but the amount of rice produced was not adequate for the entire human race. Hence, she continued to squeeze her breast to the extent that blood flowed from it, and from the mixture of her blood and milk, ruddy red rice was formed.

Upon further research, I was astonished with the similarity to the following Chinese myth:

In the time when people lived by hunting and gathering, life was very hard and uncertain. When Guan Yin saw how people suffered and often died from starvation, she was moved to help them. She squeezed her breasts so that milk flowed and with this, she filled the ears of the rice plant. In order to adequately provide for the people, she produced such quantities that her milk became mixed with blood towards the end. This is why there are two kinds of rice – white and red.

There are many folk stories throughout Asia where Guan Lin performs various acts of compassion for the people.

There are records, both in Sulu and Brunei history, of a Chinese colony on the Kinabatangan River of Sabah in the fifteenth century. This would be close to the Kadazandusun people who share the origin of rice myth. These early contacts between the Chinese and the natives of Borneo inevitably resulted in both peoples being influenced by the experience. Chinese jars and beads are found almost everywhere in Borneo. Hence, it would not be a surprise to learn that a Kadazandusun myth maker may have modified a Chinese myth on the origin of rice.

In the year 1564 Miguel Lopez de Legazpi noted numerous boats arriving from other islands with trade goods to Bohol. Bornean traders were also mentioned in his journal. Ethnohistorical sources further mention the existence of maritime polities in Manila, Magindanao, Sulu and Cebu, which engaged in competitive trading and raiding during the 15th century. It is not inconceivable that during these movements, the origin of rice myth made its way to Bohol.

Who Was Guanyin?

Guanyin is the Chinese form of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Bodhisattvas are enlightened, compassionate beings who assist the spiritual goals of others. They are often distinguished from Buddhas by their princely clothing and adornments, indicating their continued presence in the human world. The figure of Avalokiteshvara can be traced back to India. His name means “the lord who looks down with compassion.” In China, Guanyin is believed to hear the sorrows of humanity. The bodhisattva is strongly associated with a chapter of the Lotus Sutra, a popular Buddhist text that lists 33 forms that the deity can take in order to help people in their time of need. The worship of Guanyin in China began around the fifth or sixth century.

Originally a foreign, male deity from India, this Buddhist deity was eventually transformed into many forms (often with feminine features) with pronounced Chinese characteristics. The image illustrated here, while perhaps appearing slightly androgynous by Western standards, are male in gender and reflect the ethereal, transcendent figure type of many early Buddhist images.

The representation in China began transforming into a female figure during the 12th century and was thought to be entirely represented as female by the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368- 1644 AD).

In Conclusion

As mentioned above, it is generally believed that Guan Yin is the Chinese form of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. It is hypothesized that the image transformed from male to female over time. This would explain how the female image of Guan Lin, goddess of mercy, was incorporated into a Chinese folk story regarding the origin of rice. This would also fit with the Sulu and Brunei history of a Chinese colony on the Kinabatangan River of Sabah in the fifteenth century who may have brought the story. This developed into the Sabah myth of Bambarayon. It could have been Bornean traders, migrants, or the Chinese themselves that helped this myth find its way to Bohol, but I feel it is a reasonable hypothesis to call the story of Sappia a pre-colonial myth, even though its documentation did not occur until the 20th century.

The name Sappia could possibly come from the Cebuano term sapyà, said of something flat which is normally full and bulging.

The 19th day of February, in countries influenced by Chinese culture, is a day devoted to honoring Guan Yin, goddess of compassion. Perhaps this would also be the day to honour Sappia.

I admit that this hypothesis can’t be classified as anything more than conjecture, so welcome feedback over at THE ASWANG PROJECT Facebook and Instagram pages.

SOURCES:

Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas by Miguel de Loarca in 1582

Bohol Folklore, María Caseñas Pajo, University of San Carlos, 1954

Folk Tales from China, Sian-tek Lim, J. Day Company, 1944

Borneo Research Journal, Volume 6, December 2012, 75-101

Barangay, William Henry Scott, Ateneo Press, 1994

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.