The Southern Kankana-ey ethnolinguistic group includes the majority of inhabitants of southern Mountain Province in the municipalities of Tadian, Bauko and Sabangan, and the municipalities of Bakun, Kibungan and Mankayan in Benguet.

The areas occupied by these people are wholly dominated by mountain ranges with a wide range of variability. The topography is roughly characterized by steep slopes to nearly level slopes with deep ravines and small patches of gentle slopes that are· found along the riverbanks, narrow valleys and on top of ridges. The towering peaks include Mt. Kalawitan in Sabangan (2,714 meters) while the plateaus include Namiligan in Mankayan, Dalingoan in Bakun and Palina, and Madaymen in Kibungan.

The southern Kankana-ey are linguistically linked with their northern neighbors, the northern Kankana-ey. In cultural terms, they comprise a very distinct group. Although many cultural traits are shared with the Ibaloy, the languages of the two are not related since the affinity of Inibaloi is with Pangasinan.

They have been described in the early 1900s as like the Ibaloy but they celebrate their festivals “more splendidly.” There is a marked difference between their language and that of the Ibaloy. But like the latter, their settlements are dispersed. Their terraces have mud walls like those of their southern neighbors, with the same kind of cropping. In modern times, their agricultural thrusts turned more toward the production of mid-latitude vegetables which are marketed even to the lowlands and cities of central Luzon.

DNA studies in 2016 show that the Kankana-ey could potentially represent an unadmixed remnant population close to the source that may have given rise to the Austronesian expansion. This could make them among the original ancestors of the Lapita people and modern Polynesians. They might even reflect a better genetic match to the original Austronesian mariners than the aboriginal Taiwanese, the latter being influenced by more recent migrations to Taiwan.

Exploitation in the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition

In 1904 the U.S. government organized a large Philippine exhibition for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, more popularly known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. The exhibition included cultural artifacts, commercial merchandise, natural resources, and a delegation of over 1,100 Filipinos representing various ethnic groups in the Philippines (Philippine Exposition Board 1904). These groups included the Negrito, Igorot, Tinguian, Mangyan, Bagobo, Moro, and Visayan. The lgorot group was composed of seventy people from the Bontoc area and twenty-five Kankana-ey from Suyoc, Mankayan, Benguet, Seventeen people from Abra, who were called “Tinguianes:’ were also housed in what would collectively be known by fairgoers as the “Igorrote Village.” The individuals from Suyoc lived on the fair grounds for most of the eight-month duration of the fair along with the Bontoc and Tinguian.

What few people outside the Suyoc community knew then and now was that the Suyoc participants traveled to the U.S. with a pair of American brothers, Charles and Alvin Pettit, who had been soldiers in the Philippine-American War. Charles had been in the First Wyoming Volunteers and had gone to the mountains to prospect for gold. Truman Hunt, another soldier who had been prospecting with them in 1900, became lieutenant-governor of Bontoc and was in charge of the “Igorrotes” at the Fair. Charles Pettit married Dang-usan, a Suyoc woman, and together they recruited a group of relatives and neighbors to go abroad with them. Their exhibition highlighted gold mining, metalworking, weaving, and dancing; the choice of individuals to go to St. Louis reflected skills in these activities.

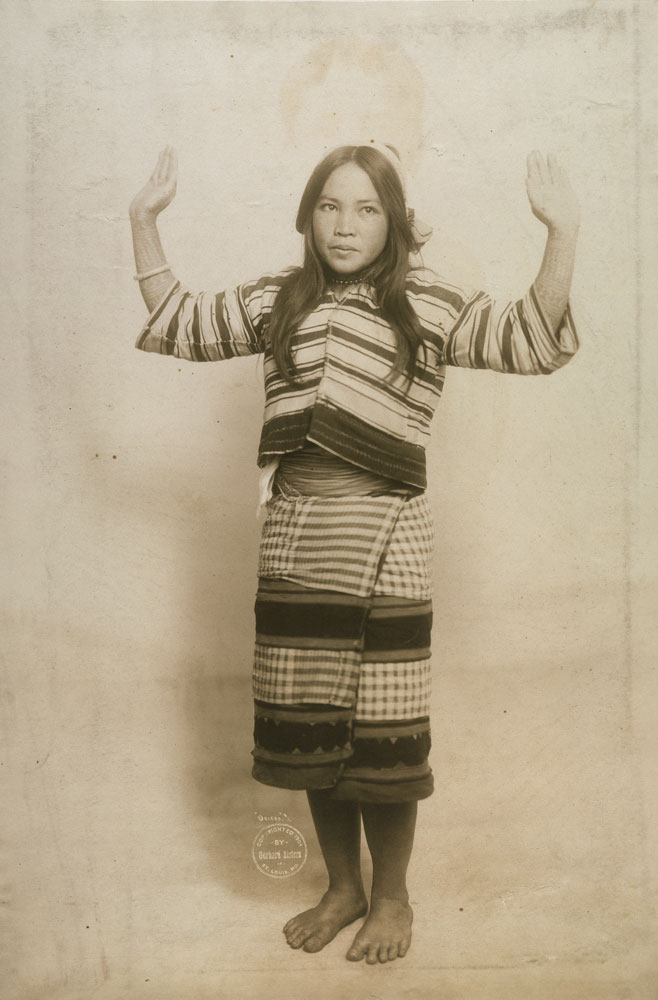

PHOTO: Gerhard Sisters

Although the Philippine Exhibition was considered a ‘huge success,’ the human zoo was controversial because of its racist and imperialistic features and the stigmas it inflicted on the Filipino people.

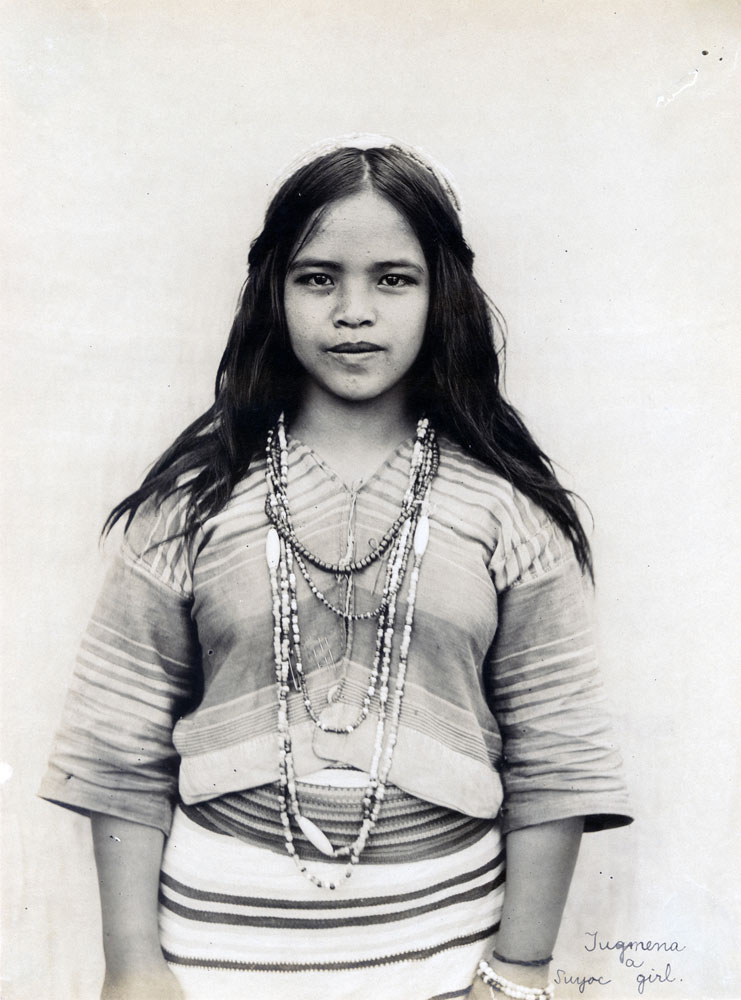

The images used in this article are members of the twenty-five Suyoc Kankana-ey Philippine Exhibition participants, so I felt it was important to share the above history and to give names and lives to them.

*Please note that the following information has been taken from historical studies and may not represent the modern beliefs or the Kankana-ey people or the beliefs of those in Christianized areas.

Religious Beliefs and Rituals of the Southern Kankana-ey

Contrary to what early writers believed, the Southern Kankana-eys do not worship idols, images and sacred places. Carved images are only displayed in the house for decorative purposes and not for anything else.

Basically, the indigenous religion is the belief in the existence of deities and spirits. The highest among these is Adikaila of the Skyworld who is believed to have created all things and ordered the universe. Next in rank are the gods and goddesses who also belong to the Skyworld. These are collectively called Kabunyan, the best known of which are Lumawig and Kabigat who taught the people their religion and other practices. Besides Adikaila and the deities, the Southern Kankana-eys also believe in the sprits of ancestors (ap-apo and kakkading) and the earth spirits

collectively called anitos.

The caption for this photo says “showing the attitude of women in dancing.” Most of the images from the 1904 Worlds Fair tended to invent “wild” or “savage” narratives for the American public. Photos were often renamed to include the terms “warrior,” “headhunter,” or “ceremonial,” removing the individual’s name. The above pose was possibly taken to highlight the tattooed forearms, which would be considered signs of degeneracy in the US at that time.

PHOTO: Gerhard Sisters

The spirits of the people long dead are called ap-apo which are usually called upon during rituals and celebrations to bring good luck to the hosts by way of omens and signs. Their living relatives call upon them to stop the underworld spirits from causing illness or misfortune to the family. The kakkading, on the other hand, are the spirits of people who died recently. As they are thought to be still lingering on earth, they are offered a few drops of wine whenever one drinks liquor. Failure to do this offends the spirits and causes the person to become insane and violent.

The anitos are the spirits living in the underworld and they are either malevolent (makedse) or benevolent (marya). They are believed to inhabit big rocks, cliffs, rivers, caves, trees, creeks, springs, lakes, and the like. Generally, the spirits are all good but when they are offended, they may turn malevolent and inflict harm and misfortune to man. These spirits are only appeased upon the offering of food, rice wine (tafey), animals, and other gifts. The benevolent spirits include the tomonga who are believed to own the animals in the forests such as boars, deer, cats, and wild fowls as well as the gold, silver and minerals underneath. The people are careful not to offend arid offer thanksgiving to these spirits so that they shall continue to be charitable to them.

Religious Functionaries of the Southern Kankana-ey.

There are three religious functionaries: the mansipok, the manbunong and the mankotom. These native priests are endowed with a keen memory of ritual procedures and genealogies. They are respected and looked upon by the people for they are believed to possess certain powers like ritual counseling, healing, and reading and interpretation of sigtis and omens. They also supervise and administer rituals aside from their role as ritual advisers.

1. Mansip-ok. The mansip-ok is the seer or the diviner. The people consult him to determine the cause of an illness or misfortune and to prescribe the corresponding ritual. He finds the cause of illness by using various methods such as baknew and sip-ok. In the baknew, the mansip-ok breaks a chicken egg and pours its contents on a gabi or banana leaf. After praying to Kabunyan the mansip-ok observes the egg and interprets the sign and gives the possible cure. Instead of a chicken egg, the mansip-ok may also use the blood of the sacrificial chicken. Other mansip-oks determine the cause of illness using a flint tied on a piece of string. The string is allowed to swing freely in one direction and when the object becomes unusually heavy upon mention of a probable cause, the mansip-ok interprets it as the possible cause. This method is called sip-ok.

2. Manbunong (mambunong to the Kankana-eys of Bakun, Benguet). When a sick person is diagnosed by a mansip-ok to be sick because he has offended the spirit of his dead ancestor or he has forgotten to offer the necessary ritual for a long dead relative, a manbunong is called to perform the appropriate ceremony. The manbunong communicates to the spirit and invokes it to relieve the sick person of his afflictions. He then comforts the sick. individual and assures him that he shall get well because the necessary healing ritual has been properly done.

Aside from being a healer, the manbunong also acts as a comforter in times of distress, an exalter in times of victory, and as a guide in planning for thanksgiving celebrations like sida or cañao.

3. Mankotom. These are wise old men well experienced in the life and ways of their people. They oversee the strict observance of the traditional practices, customs and traditions of the community, and they are sought for their advice and wise decisions during disputes.

As religious leaders, the mankotom may perform the roles of the mansip-ok and the manbunong. Sometimes, they are even consulted by the mansip-ok regarding the appropriate ritual procedure. They are consulted to read and interpret omens (gibek) such as strange dreams and other nature signs, and prescribe the corresponding ritual. For example, if a strange dream is interpreted as a bad omen, the mankotom suggests that the puk-kay ceremony be performed to ward off the evil effects of the dream. However, if a dream is interpreted as a good sign, the sangbo ritual is suggested. In any ceremony, the mankotom are the ones who read the bile and liver of the sacrificial animal.

Six year old Singwa was one of the most photographed boys at the fair. He returned to the Philippines and settled in Tuding, Itogon, Benguet, adapted the first name Victoriano, got married, but had no children. He died in 1968.

PHOTO: Gerhard Sisters

Sample Ritual of the Southern Kakana-ey

The majority of the ceremonies are celebrated primarily to avert misfortunes or calamities and to appease the vengeful spirits that cause sickness to individuals that have offended them. This has resulted in a belief system that is primarily concerned with healing rituals (dilus) and thanksgiving ceremonies (sida).

The following is a ritual observed by the Southern Kankana-eys. The terms may, however, vary from place to place but the purpose and procedure are more or less the same.

Pedit. This is a graded feast that starts with the teteg that is performed to culminate a wedding ceremony. A pig is butchered and offered to the Kabunyan and ancestors so that they shall bring good luck and prosperity to the newlyweds. After a year, the couple performs the tolo ritual where they may butcher chickens, cows, and carabaos in addition to the required three pigs. Kintoman rice is pounded and fermented into rice wine (tafey) and animals are procured in preparation for the activity. A messenger is also sent to the houses of the couple’s relatives and other villagers to invite them to join in the merry-making, dancing, singing, and playing of the gangsa (a single hand-held smooth-surfaced gong with a narrow rim) during the said occasion. As usual, the old men performing the rituals implore the favor of the deities and anitos.

After the performance of the teteg and the tolo, the couple may celebrate the next stage, lima, that involves the butchering of five pigs. If they have the means, they may also perform the pito (7), the siyam (9), sawa-esa (11), and so on. The last stage is called beng-ngey that involves the butchering of 25 pigs. However, people of extreme wealth may celebrate beyond the beng-ngey.

The number of pigs butchered in the stages of pedit is always odd. This stems from the people’s belief that odd numbers are lucky numbers. The extra pig is believed to signify abundance to the pedit hosts. The even numbers are taboo because they signify gepgep or end.

Sources: Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera, Cordillera Schools Group, Inc., New Day Publishers, 2003

The Suyoc People Who Went to St. Louis 100 Years Ago: The Search for My Ancestors, Antonio S. Buangan, Philippine Studies Vol. 52, No. 4, World’s Fair 1904 (2004), pp. 474-498 (25 pages) Published By: Ateneo de Manila University

1904 World’s Fair: The Filipino Experience, Jose D. Fermin, Infinity Publishing, 2004

Peoples of the Philippines: Kankanay/Kankana-ey, https://ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/culture-profile/glimpses-peoples-of-the-philippines/kankanaykankana-ey/

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.