Everyone could use a little help from a DIY (do-it-yourself) guide: cooking meals, repairing machinery and operating electronics. From the simplest task to the most complicated, our generation often seeks a friendly-user guide. Tons of “how to” guides are now a staple of social media and streaming sites; providing a practical step by step for almost anything.

But how about our ancestors? Did they also have these so called “how to” guides? If so, what are some of the things that they did in accordance with these guides? This thought led me to create these five “how to” guides that will enable us to see how the early Filipinos conducted some of their activities. *Disclaimer: These activities were conducted by those with a ‘supernatural’ flair. Results may vary.

Image Source: http://www.ichcap.org

#1 How To Summon A Rain God

Well, not exactly the concrete appearance of their god but a manifestation in the form of rain. The majority of our ancestors depended on the rains for agriculture and to survive their day to day lives. Drought sometimes arrived like a thief in the night and left their crops wilted and the soil dry. However, they had their ways on how to call upon the aid of their gods and bring rain to their lands.

The Bontoc from Mountain Province invoke their god/ culture hero Lumawig in an intricate rite called Erwap to save their land from the scorch of the El Niño dry spell. First, all the men and their elders would go to Mt. Kalawitan armed with their weapons and a chick inside a small basket. Along the way they will let the chick chirp so their anito will know that they will be coming to ask for help. Upon reaching the peak of the mountain they will build a fire and start dancing. The oldest of them will recite Kapya; a prayer that asks for the rain to come. After that they will return to their village and continue their ritual dance while banging a gong all through the night. The next day they will go to the river to wash the gong. Later they will sacrifice a chicken for their god. In the following days they will continue to dance and sing to call forth rain in the sky. When there is no hawk seen flying above, they will then fetch a pig for another sacrifice.

If rain is still not pouring, they will increase the sacrifice into five pigs and continue their ritual dance. In between these days they also conduct what was called Tengao wherein everyone stops work for the whole day to focus on the ritual.

If still nothing happens, the people will perform Layaw where they show their desperation to Lumawig by beating one another and stealing the possessions of their neighbors; displaying discord among themselves to finally gain the mercy of their god.

In this instance, I may instead refer you to a DIY guide on irrigation.

#2 How To Create a Sigbin

Having an animal companion was an innate trait of our ancestors. They trained dogs to hunt with them and some of them even buried their loved ones together with their favorite dog – observed and examined by Timothy Vitales in his article in the International Journal for Osteoarcheology. Animals seemed to play an important role in their community which may explain why most of us today are fond of pets. The askal is the native, primitive dog of the Philippines.

However, having an animal companion for them was not limited to man’s best friend and other ‘normal’ creatures. There are some tales that talk of our ancestors keeping a supernatural creature called Sigbin; a creature that has a hybrid appearance usually combining a dog, goat, or human characteristics. Nonetheless the said being can bear the ability to fly and transport its master anywhere. They are also so fierce in protecting their owners that they will kill whoever harms them.

Image Source: http://www.mangkukulam.com

The Sigbin is invisible to most. In order to see it, you must put the tear of a dog in your eye.

So how can someone have their own Sigbin? According to post-colonial legends, these creature are made from an Angelica plant (Bryophyllum pinnatrum) placed inside a bottle during the Lenten season. In alternative versions, the Sigbin are born from the roots of a vine like plant called Nito placed in a bottle with a special oil. The Sigbin will immediately take its adult form during a full moon.

Once outside the bottle, the Sigbin must be fed with the blood of a white chicken every full moon. When you can not provide a chicken, you must cut a part of your body and let it lick the blood. Failure to do this will cause the Sigbin search for the blood of a baby to feast upon.

#3 How To Change Your Name

Most of our ancestors possessed an ethnic name long before they were baptized by the Spaniards and started assigning names based on Catholicism. For Ilocanos, birth and marriage may not be the only time their name changes throughout their life. When a child is afflicted by a great malady, the shaman of one’s village will conduct a ceremony called Buniag ti Sirok ti Latok.

This rite was done to confuse the anito who caused the child to suffer from a mysterious or incurable disease. Like other common rites, the shaman will offer a sacrificial animal to appease the anito. He or she will do this as he places the following in the ground: a kotibeng (guitar like instrument), a saber, a lance, coconut palms, eggs and a silver coin. The shaman will then perform a ceremonial dance around the child. Later they will kill the sacrificial animal; burning its skin in the process and divide it into two. One will be offered to the Anito and the other will be eaten.

After eating the skin of the animal, the Shaman will draw a cross like symbol on a wooden plate or Latok and proclaim that he will change the name of child so that the Anito will leave him or her. A man who ignores the new name will get a hernia while a woman will encounter uterian problem.

#4 How To Catch A Thief

Sorcery and magic is often inclined towards flashy invocation elements and the summoning of entities. It is too grandiose to apply for our daily lives – where we try to lean more on practicality. But not all ancient magic demands lots of ritual items, confusing symbols and elaborate chanting. Some are so simple that even the untrained ones can do it. The good news is that it can be applied to solve a problem that some of us have already encountered in our lifetime. Theft!

In order to catch (and possible get good old fashioned revenge) anyone who steals your belongings, a Bongat ritual was done by the Bagobo. First, gather a powder and place it in two Bamboo joints. Second, take an egg and make a hole in it. Sprinkle a little bit of powder on that hole and let it burn in the fire. A potential thief will eventually confess their crime due to the excruciating pain that they will suffer.

In other cases when the thievery is unforgivable, others will be more merciless and instead break the egg instead of burning it, which will kill the thief.

#5 How To Use Bakunawa In Building Your House

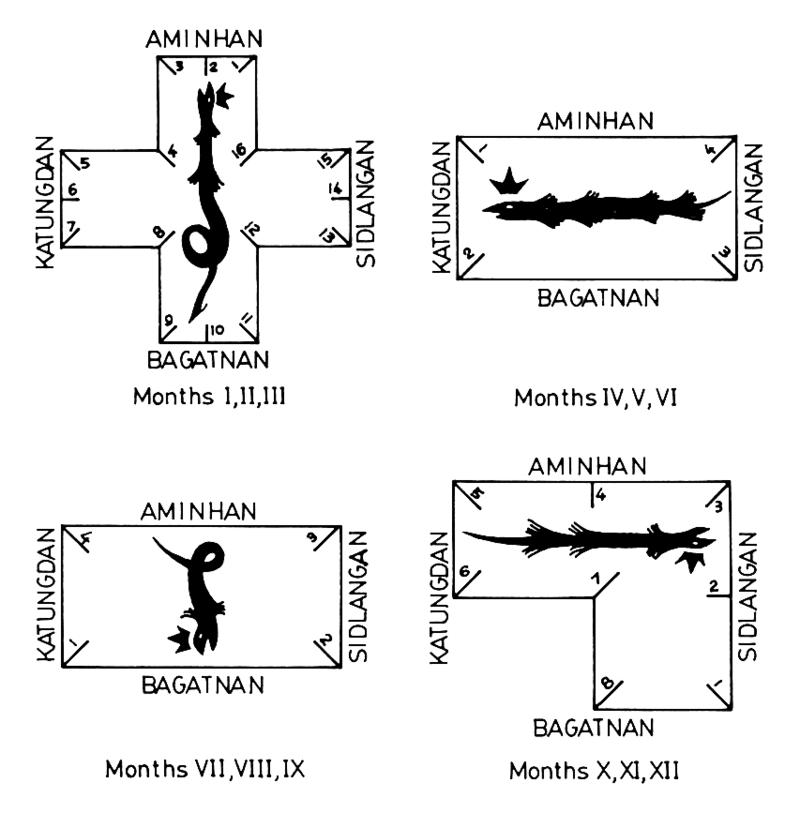

Surprisingly the resident moon eater is not always an envoy of catastrophe. There is a Bakunawa chart that was used to indicate the position of the mouth and tail during certain times of the year which translates to the direction your new home should be build in. The year will be divided into four phases and in each phase the mouth and the tail of Bakunawa will shift.

In the first phase (January, February and March), the Bakunawa’s mouth is in the north and its tail in the south. One must avoid building a house in the direction of the mouth or bad luck will befall their home. A house build in January is called Balay nga Palamugnan. Those who live here will experience a bountiful of harvest. In February, houses are called Balay Sang Mga Abyan and its dweller will have many friends who help them succeed. Houses built in March are called Balay Sang Mga Kaiwaton, Hilu, Kahisa, Kaburingut Kag Hinali Kang Kamatayon (House of hardship, poison, jealousy, hatred and sudden death). In a basic sense this month is the worst of all the months to build a home.

In the Second phase (April, May and June), the Bakunawa is facing the west and its tail is in the east. Houses built under the month of April are called Balay Sang Kabuhi (House of Life) and will bless its dweller with long life. Houses built in May are called Balay ti Mangad (House of Wealth). As the name implies the Bakunawa shall guide the dweller of this house to good fortune. Same goes also for those who build their house in the month of June.

The Third phase (July, August and September) finds the Bakunawa’s mouth in the south and the tail in the north. Houses built in July are called Balay Sang Manggad Kag Panubhilon Sa Ginikanan (House of Wealth and Inheritance) wherein the owner will inherit great fortune from a family or friend. Houses built in August are called Balay Sang Dult Kag Ginihatag Nga Kapuslanan (House of Gifts and Useful Things) as it blesses the owner with numerous help from their neighbors. September is also considered a month of ill-fortune and houses that are built under this month are called Balay Sang Mga Kalisdanan, Kalautan Kag Pamalatian (House of Misfortune and Disease) and its dweller will suffer prolonged sickness.

The last phase (October,November and December) shows the Bakunawa facing east and its tail in the west. Houses built in October are called Balay Sang Magtiayon Kag Kinasal (House of Marriage). Unmarried members of the family who live in this house will contract an unexpected marriage proposal. Houses built in November on the other hand are called Balay Sang Pangulba, Kahadluk Kag Kamatayon (House of Fear, Fright and Death). This month is also filled with bad luck since it will bring crisis, fights and illnesses. Last is the month of December which is a good month to start anew. Houses built under this month are called Balay Sang Pagkaluoy, Pagtuluohan, Panlakatan Kag Katarungan (House of Mercy, Religion, Travel and Righteousness). Those who dwell in the said house will live in a righteous way, travel far and have religious experiences.

SOURCES:

Isabelo’s Archive by Resil Mojares (2013)

Encyclopedia of Philippine Folk Beliefs and Customs by Fr. Francisco Demetrio, S.J (1991)

El Folklore Filipino by Isabelo Delos Reyes, Translated in English by Salud C. Dizon and Maria Elinora Peralta-Imson (1994)

ALSO READ: How to Travel the Underworld of Philippine Mythology

Currently collecting books (fiction and non-fiction) involving Philippine mythology and folklore. His favorite lower mythological creature is the Bakunawa because he too is curious what the moon or sun taste like.