Birds and serpents have always been a common motif in mythological tales. Often, they are connected with spirituality as they represent deities and other supernatural forces governing the cosmic balance of the upper and lower world. Both animals posses qualities beyond the comprehension of ancient people; inciting fear and awe in the eyes of the first men who witness them; the glorious flight of bird that made them one with the sky and the deadly yet graceful movement of a snake crawling in the crevices of the earth.

Early Filipinos venerated these animals and had them play a major role in various ethnic lore throughout the archipelago. Let’s look at how these creatures bridged the narrow gap between Filipinos and their spirituality.

The Bird and the Serpent are two major motifs/symbols that can be found in many mythology including in the Philippines

Guardians of Two Worlds

Before our ancestors believed in the concepts of heaven, hell and purgatory as the primary layers of the cosmos, they already held a certain belief in a multi-layered world consisting of the sky-world, the word of men, and the nether or underworld. Each layer had a different name depending on the ethnic group. For example, from the works of T. Valentino Sitoy Jr., the sky-world is called as Kahilwayan by Visayans from Panay, while other groups label it as the Kaluwalhatian. In an article written by Lorenz Lasco in Dalumat Ejournal, he cited that the sky-world’s own “anito” is the Sun which is symbolized by a bird and the underworld is ruled by spirits resembling snakes and other reptilian looking mythical beings such as dragons and crocodiles (Buwaya).

Below the Earth, according to a story from the Manobo group in Mindanao, a large serpent was said to guard the pillar supporting the Earth – which is parallel with the Bukidnon lore about Intumbangel, the colossal snake below. Two natural phenomenon are said to be associated with the mythological snake: first is an earthquake, which is the result of the giant serpent moving below the earth, and second is the eclipse when it is said to try and eat the sun or moon – a common motif most popularly associated with Bakunawa. The Higaonon people from Mindanao believe the sky is held in the talon of a great bird known as Galura and the flapping of its wings causes strong winds that act as a buffer to the middle world where mortal resides.

Both serpents and birds bear the feminine and masculine essence which are also prevalent in different myths from around the globe. Due to its closeness with the Sun, which is filled with ‘male energy (fire and light)’ birds are considered a masculine symbol. The serpent, unlike Christian motifs, is often the female symbol as associated with “mother earth” motifs. In Borneo, the serpent is a much favored spirit for it dwells much closer to the human realm. The serpent is known to have a disposition, like a mother, who always takes care of man as if they are her children.

These two different beings hold the dualistic element of male and female energy; the yin and yang that fuse together to form harmony and balance in the world.

(Image Credit: Manaul by Kwehrek on DeviantArt)

The Cosmic Bird as the Creator

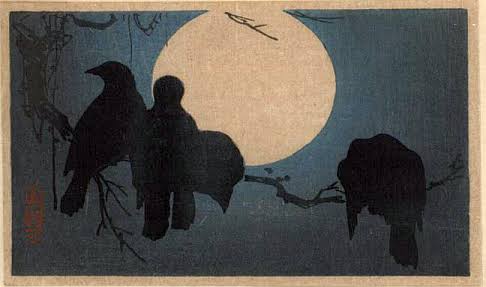

As a symbol the bird embodies man’s aspiration to fly and be free from the constraints of the world. In a spiritual sense, it means being able to surpass the physical and mortal limits and able to ascend to the higher realm of consciousness. No wonder many gods and goddesses associate themselves with various kinds of birds – like the Owl for Artemis, Falcon for Horus, and Crow for Odin. Meanwhile, the chief sky lord of the Tagalogs was known to be represented by a small, azure color bird known by the native as tigmamanukan (Philippine Fairy-bluebird). In other sources, this bird is actually colored yellow and lives in a holy mountain called Batala. According to Fr. Pedro Chino in his book Relacion, the Tagalogs respected this species of bird to the point that they also named it Bathala; the same name as their most powerful god.

However from the lore of the people of Mandaya in Eastern Mindanao, birds don’t only bear the name of their gods; they are the ones who posses the power of creation itself. The Limokon, is a legendary bird who can speak to humans. It is said to have laid two eggs – one in the mouth of river Mayo, which hatched the first woman, while the other was laid near the source of the river and hatched the first man. The tribal historians of the Tagakaolo in the Davao region tell us that they are descended from Lukbang, Mengedan and Bodek,is wife. These three persons lived on a small island. Two children were born to Mengedan and Bodek: Linkanan and Lampagan. These two, in turn, became the parents of two birds, Kalau and Sabitan who flew away and brought back bits of soil which the parents moulded with their hands until they formed the earth. Other children were born and through them the world was peopled.

In the story of Malakas and Maganda, a bird that goes by the name of Manaul cracks the bamboo stalk where the first primordial man and woman surface. In another version of this creation myth, Manaul was regarded as the king of all the birds in the universe. Despite his high status, Manaul shows unspeakable flaws; he devoured his counsellors, the owls, and cursed them to stay awake all night by making their eyes wide. He was imprisoned for unknown reasons and later escaped and sought vengeance with king of the wind, Tubluck Laui. The clash of these two being resulted in the intervention of the supreme god of the Visayans, Kaptan, wherein he sided with Tubluck Laui and pummelled Manaul with huge rocks from above. Manaul survive the wrath of Kaptan and the rocks the god had thrown remained in the sea and became the earth.

While Manaul can be a fusion between a beneficent yet antagonizing figure, the origin story of Bohol projects birds as the savior of a woman from an ancient sky dwelling people. This unnamed woman who fell from the sky was caught by Gakits (wild ducks). As the story progresses, the Gaktis brought the sky woman to a huge turtle who turned out to be the island of Bohol where she would live and become the first mother of the Boholanos.

Serpent as the Familiar of Goddess

During the ancient period, many looked upon serpents and snakes as a miniature replica of mighty dragons they revered as guardians of the nature world. There is no question about the important role of snakes in world myths. Commonly distinguish as a modern universal sign of evil and deceit, serpents used to be among the most sacred animals in different ancient belief systems – including shamanism. They are known to symbolize wisdom, fertility, beauty, and like the bird, divine status was also given to them.

Francisco Demetrio wrote in his work entitled Creation Myths among Early Filipinos, “We have pointed out that the central pillar of the world is analogous to the motif of the centre of the universe. And that one of the characteristics of the centre in mythological thought is that it is “difficult of access;” because it is there that passage is made possible from one cosmic zone to the other; it is there, too,that the tree of life is located,and the food of immortality secured. The tree of life is often depicted as guarded by a monster, a snake.” The same image also appeared in the Manobo tales of Dagau, their creator goddess who acted as the sentinel of the pillar supporting our world together with her serpent who caused earthquakes each time it moved. The said myth may also parallel the motif in the story of Nidhoggr from Norse mythology which is also a serpent-like dragon underneath the roots of world tree, Yggdrasil.

The Bagobo have their own version of the goddess and serpent myth, but altered it in a way that there is no world pillar. Eugpamulak Manobo, the deity who created the sun, moon and stars also gave life to a fish-like snake being called Kasili (Eel) – who instead of dwelling below the world, wraps itself around it.

Ancient Bikolano stories picture the goddess and the serpent as archenemies instead of companions. The masked goddess Haliya protects the moon from the ravenous Bakunawa who tries to eat it – an event which is repeated each time a solar eclipse appears in the sky. There is even said to be a ritual that was performed by ancient Bikolanos in order to summon the help of Haliya to fight the Bakunawa.

William Henry Scott detailed a specific connotation of serpent as one of the sacred beings, or Diwata, of the Visayans who often regarded them as personal guardians or companions. The Umalagad were often brought for protection and luck during sea voyages or raids.

On Divining the Future

Together with the constellations that guided and foretold the future of man, animals were also known to provide signs for people to read and understand their fate. Birds of omen are prevalent in our diverse lore. In Tagalog, a bird known as Balatiti gave warnings to those who heard its cry – which could be interpreted as good or bad. Igorots called this bird Labey or Balbalisbis while the T’boli’s Limuhen is a personal messenger of the gods, delivering signs and warnings to people.

Another mythological bird that is said to aid farmers in selecting the best land for their crops is Almugan from the Blaan people of Southern Mindanao. Farmers will wait for the cry of Almugan to signify that the land is good for planting and sowing. Once the farmer hears its cry, they will align four 60 centimetre Bamboo sticks on the ground towards the direction Almugan. If these Bamboo sticks stay standing erect, the land where they are put will have a fruitful harvest. If they don’t stand straight, the farmers must find a different plot to repeat the ritual.

Blaan people also used the cry of Almugan for signs in their homes. It gave warning through its cry whether their is someone unfamiliar approaching, or during night, the cry is an alarm that there is some malignant force lurking in the vicinity.

Surprisingly, the Bakunawa was also used by ritual specialist in determining the sixteen directions of fortunes and misfortunes. Every calendar year, the great serpent changes it position in a sudden counter-clockwise ninety-degree movement. To avoid misfortunes, one should avoid the direction where its mouth is pointing – in regards to travel, marriage, and other various aspects of life. Home builders used the position of Bakunawa to avoid constructing framing in directions that may misfortunes, sickness, or death to the owners. This can be compared to the Chinese art of Feng-Shui where it encompasses auspicious directions and animal symbols to identify one’s fortune or to avoid bad luck.

As above, So below

Philippine mythology is a complex labyrinth loaded with intricate symbols and deep motifs that constantly challenge our understanding of the ancient beliefs, values and culture that is stitched together with tales and narratives from our ancestors. For every twisting path inside this labyrinth lies the door where knowledge and wisdom can be attained. We Filipino can only know the way towards it once we learn how to find balance within ourselves – the bird and the serpent that dwells in our soul, the above and below that colors the microcosms within the archipelago, and the destiny within our roots that awaits our curious minds to unfold.

Currently collecting books (fiction and non-fiction) involving Philippine mythology and folklore. His favorite lower mythological creature is the Bakunawa because he too is curious what the moon or sun taste like.