Two medical systems compete in Cebuano society: modern, scientific medicine, and folk medicine. Sorcery is one of the causes of illness according to folk medical etiology, whereas modern medicine does not attribute illness to magic. However, since Cebuanos have a choice between folk medicine and modern medicine, and since that choice may crucially affect, and be affected by, suspicions of sorcery, the competition between folk medicine and modern medicine in Cebuano society will be fully considered. However, first we begin with a discussion of the folk medical system. Sorcery is a social phenomenon, but it is a medical phenomenon as well. Since an effective sorcery attack is “known” by the illness of the victim, sorcery is significantly connected with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of illness.

Cebuano folk medicine is extremely complex, rich in various concepts, diagnoses, and treatments of disease. To do the folk medical system justice in its own right would require a major treatment that is far beyond the scope of this work. Under the circumstances, we will limit ourselves to a brief summary that will indicate something of the general character of folk medicine and its relationship to sorcery.

There are three medical roles in the Cebuano folk medical system. They may be assumed by either men or women, and the same individual may combine two or all of them in his practice. The masseur (manghihilot) primarily treats what are diagnosed as bone dislocations and fractures, but he may minister to other ailments as well, such as respiratory illnesses, swollen lymph nodes, or certain gastric and nervous disorders called kabuhi. (A Filipino physician identifies the kabuhi syndrome as gastro-intestinal neurosis.) The manghihilot also massages the abdomen of expectant mothers to make sure that the fetus is properly placed in the womb. The midwife (mananabang) is concerned with the actual act of delivery, as well as with the pre and postnatal problems. The mananambal is a general healer, and, as the practitioner who handles illnesses imputed to sorcery, he will be the focus of our discussion of folk medicine.

The great variety of illnesses treated by mananambal fall into two broad categories. First, there are those maladies which are regarded as “natural,” attributed to physical or psychic phenomena of the everyday world and not initiated by any spiritual being, sorcerer, or witch. In folk medical etiology, the causes of natural ailments may include change or irregularity in habits; faulty diet; fatigue; exposure to wind, cold, or heat; fright; worry; relapses; and complications or vulnerability arising from previous ailments. In the second category of illnesses are those which are regarded as “not natural” in provenance. These may be ascribed to sorcery, witchcraft, possessive or neglected ancestral spirits, other dangerous spirits outside the pale of God, and gaba, a curse that comes from God as a punishment for certain moral offenses, especially disrespect for parents and other elders or abuse of natural resources.

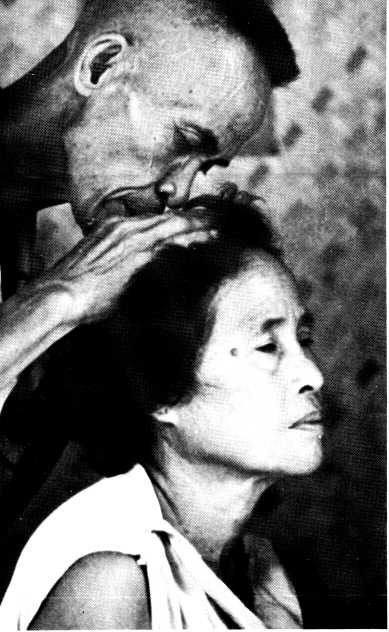

For diagnosis of illness, mananambal depend on diverse sources of information. Symptoms of patients—such as pain, lesions, swelling, or fever—are primary clues. For most mananambal, the pulse of the patient is a key sign of his condition. In the words of one practitioner, “The pulse is the best spot to tell the illness of the patient because it is an outlet, a ‘substation’ of the heart. If the pulse lies, then the heart lies.” The character of the pulse is an important criterion for determining whether an illness is natural or supernatural, since it is widely believed that if a patient has symptoms which ordinarily are accompanied by an abnormal pulse, and if his pulse instead is normal, this is an indication that his illness is not natural. In addition to present symptoms of the patient, knowledge of his medical history and experiences he has had which may be relevant to the inception of illness can be of great diagnostic value to the mananambal. But whereas the diagnosis of the mananambal may be based on manifestations of illness in his patient or on the background illness in his patient, the mananambal‘s knowledge about his patient’s condition often is said to come from spirits, saints, or God, whom he consults about the case. Sometimes the mananambal gains this information through devices that are used to secure responses from supernatural sources to questions the mananambal asks about his patient’s illness. To cite just one example, a mananambal embeds the tip of a large pair of scissors in a winnower, called a nigo, and he secures the scissors with string. He and another individual stand on either side of the winnower, and each holds a finger under one of the handle loops of the scissors, so that the winnower is suspended on their fingers. The mananambal then asks questions about his patient’s illness, such as, “Is the illness natural?” If the answer is “no,” the winnower remains in the same position; if the answer is “yes,” the winnower turns. Other mananambal do not depend on instruments to transmit diagnoses from spiritual sources; they “hear” what they need to know directly from these source. For instance, one mananambal said he puts his hand on a new patient’s head, and a voice whispers in his right ear informing him what the illness is. Information from spiritual sources may include prognosis as well as diagnosis. One mananambal said that his mentor, St. Joseph, always tells him when it is time for a patient to die. Another mananambal said he burns candles when he prays in the night for his patients, and if the candle burnt for a particular patient droops, or if the flame decidedly flickers, this means the patient will die.

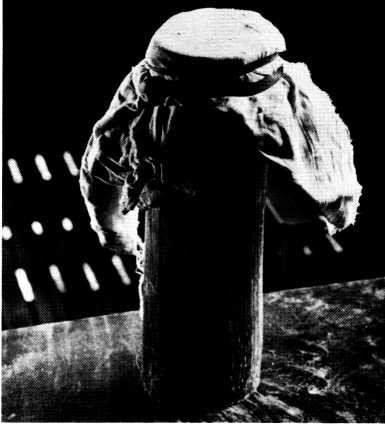

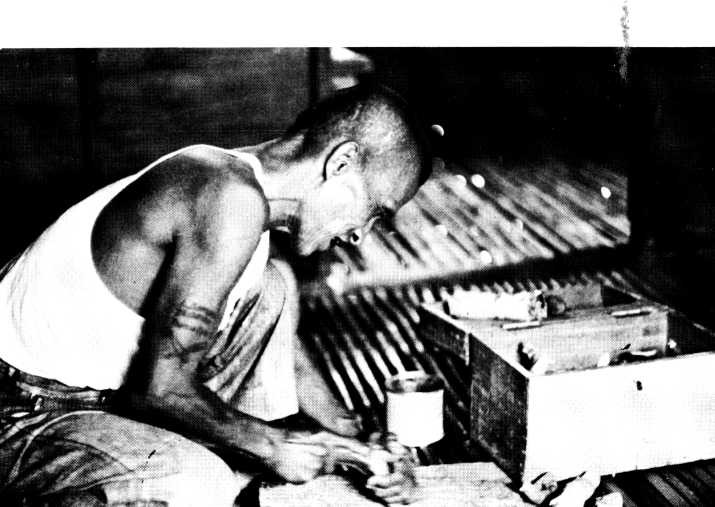

Mananambal may utilize a wide variety of treatments for their patients, including decoctions, poultices, fumigation, anointing, cupping, prayers, incantations, and diverse magical procedures. Most mananambal are herbalists, and the pharmacopoeia of Cebuano folk medicine contains a great number of medicinal plants. Such plants are employed primarily for the treatment of what are regarded as natural malfunctions, but some of them may also be used, in a magical context, for the treatment of supernatural maladies. Thus, there are mananambal who collect plants and other ingredients during Holy Week, and these are mixed with coconut oil on Good Friday. Such “sacred” medicinal oils, usually rubbed on the patient but at times prescribed in small amounts for internal use, may be employed by some mananambal for the treatment of virtually any illness; these sacred oils are among the most important medicines for healing illnesses diagnosed as supernatural.

Illnesses attributed to sorcery may be treated with prayers and incantations, sacred medicinal oils, and a variety of other means, some of which are applicable to a range of illnesses (for example, palina, a fumigation technique, is designed to purge the patient’s body of foreign objects, regardless of whether they were introduced there by spirits, witches, or sorcerers), whereas others are specific for maladies produced by certain types of sorcery. To illustrate, the feces of tawak, an insect used in barang, are supposed to be efficacious for the treatment of illnesses attributable to that form of sorcery. Or, to take another example, for illnesses caused by paktol, in which nails are pushed into a doll representing the victim, the patient drinks water which has been boiled with nails in it.

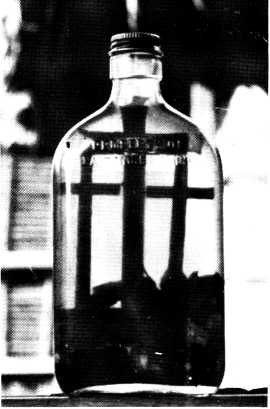

Patients go to mananambal not only for the treatment of illness but for its prevention as well, and some mananambal provide amulets for those who wish to safeguard themselves against afflictions that might come from spirits, witches, or sorcerers. Things considered magical or holy, such as mutya, stones thought to possess miraculous properties, or fragments of religious objects secreted from churches (e.g., a chip from an altar or threads from vestments of a priest), are sewn in small pouches or put in miniature bottles filled with coconut oil. These amulets, called sumpa, are generally secured from mananambal and are among the most popular amulets in the area.

From what has been said to this point, the prevalence of magico-religious elements in Cebuano folk medicine is obvious. This, however, is not to slight the importance of empirical knowledge and procedures in the folk medical system. Mananambal generally possess detailed information about folk disease categories. Empirical evidence of their patients’ illnesses is examined in the light of this information when mananambal make diagnoses and prognoses or solicit them from their spiritual patrons, and the curing properties of medicinal plants are known and frequently relied upon in treatment. But often even what is seemingly only a direct physical treatment of illness is partly magical, and the mananambal may have acquired information about the treatment through mystical experiences. A mananambal may prescribe a relatively simple decoction for an illness, using leaves of a few plants. However, the leaves will have been picked from the east side of plants because that is the direction in which the sun rises. And the prescription itself, although it might contain only leaves of plants that are commonly known in the area for their medicinal qualities may have been “revealed” to the mananambal as an efficacious cure by his spiritual mentor in a dream or vision. In such cases, empirical knowledge is defined as divine knowledge, and the role of the mananambal in general is predicated upon divine sanction, as demonstrated in the special aid he derives from spiritual sources and the cures credited to him.

Folk medical practice is culturally defined as a role of service, and the practitioner is not supposed to profit from the medical aid he offers. It is often said that healing knowledge and power are conferred upon a practitioner by a spiritual mentor on the condition that he will use them only to help others and not for personal gain. However, if the practitioner is supposed to treat his patients for the sake of service rather than profit, the patient has the obligation to offer at least some token of gratitude to the practitioner, and this debt is given greater force by a folk medical belief that the medicine will not work unless something is given to the healer on behalf of the patient. This payment is usually made in cash, although patients from rural areas sometimes bring farm produce to a practitioner instead. Some healers emphasize that their purpose in practicing medicine is not financial gain by avoiding any overt action to take money from their patients, and they will not accept money if it is put in their hands by patients. Their patients may leave money on a table or stuff it in the shirt pocket of the healer, who seemingly ignores the payment at the time, although he will not refuse it. Other healers are quite explicit in making it known to their patients that they expect to be paid, and they show no hesitation in accepting money directly from their patients. In fact, regardless of the ideals of folk medical practice, it is often strongly commercialized, especially in Cebu City.

SOURCE: Lieban, R.W. (1967). Cebuano Sorcery: Malign Magic in the Philippines. University of California Press

ALSO READ: Philippine Sorcery 101: 6 Methods and How to Counter Them

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.