Every once in a while over at The Aswang Project Facebook page I find myself moderating a challenging discussion. Often, it is a subject I don’t feel is within the periphery of my study so I tend not to share my personal feelings about it. Some of these topics come up often enough that it can hijack conversations and discourage constructive discussions. One such topic involves the terms “Philippines” and “Filipino”. I understand the decolonization movement and why these terms can be of contention, so I try to stay neutral with other people’s affinity towards changing these names – the exception being the “Maharlika” movement (another challenging topic) in which I explored its evidentiary value.

That said, I won’t pretend that my subjectivity doesn’t exist. I often structure my articles and presentations using the opinions of academics who saw the value in exploring prehistory. Part of this is not focusing so much on the current name of the country, or collective noun of the people, as much as showcasing and celebrating the ethnolinguistic differences. One scholar whose opinion I respect is the renowned anthropologist F. Landa Jocano. Below you will find Jocano’s take of the term “Filipino”.

Before we get to that, I think it is important to look at history through different lenses and question things that you feel should be challenged. However, contempt for the Spanish shouldn’t lead to an automatic rejection of everything they named and documented. Methods of hypothesis elimination or cooperative argumentative dialogue tend to work much better when finding truths about the precolonial ‘Philippines’. As an outside observer, it is clear to see that the term “Filipino” has been largely transformed through a linguistic evolution. Its meaning today has less to do with the historical King Philip II, ruler of the Spanish Empire, than it does with the more modern and culturally defining “Filipino pride”.

The Term “Filipino”

(*Note, May 25, 2021: F. Landa Jocano’s commentary begins here)

The first concept we need to clarify is the term Filipino. Many concerned students, scholars, and laypeople have questioned its usefulness when applied to our prehistoric ancestors. They say we were not called Filipinos before. This is understandable because the term is of recent origin . We have no way of knowing the prehistoric name of the archipelago (even if some authorities say it was known to the Chinese as Ma-i, referring to Mindoro or to people living on the different islands). Some leaders, in the past, had suggested the. term Maharlika as the alternative name for our country. But the nationalists objected, saying that this term is Sanskrit in origin, therefore, also alien to our culture. The term Maynilad had also been suggested, but those who objected to its use said that it was derived from a plant found among the Tagalogs. Other ethnic groups might protest against its use and is therefore divisive rather than unifying in function.

In the face of these controversies, we suggest that we retain the term “Filipino.” Historically, the Spaniards first used the term. When Ferdinand Magellan, the Portuguese explorer who was working for the crown of Spain, came in 1521, he called the islands San Lazarus, in honor of the saint. When Ruy Lopez de Villalobos, another explorer, came in 1542- 43, he called the archipelago Felipinas, in honor of Felipe, the son and later successor of Carlos I, King of Spain. Originally, the name referred only to Leyte and Samar, but it was later applied to the entire archipelago.

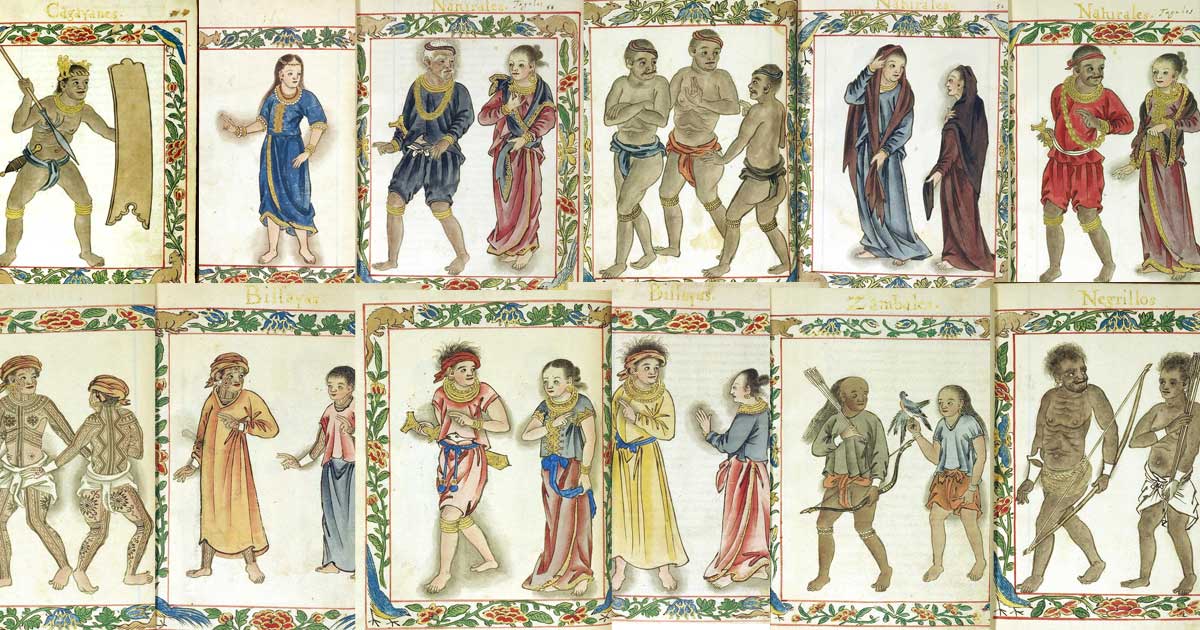

The early Spanish chroniclers called the natives by the language they spoke: Bisayans, Tagalogs, Ilocanos, Kapampangans, etc. Sometimes, the generic term pintados was used to refer to the Bisayans because they were elaborately tattooed. Frs. Pedro Chirino and Francisco Colins used the word “Filipino” to refer to the natives of the communities where they worked. But the later colonial administrators and writers changed the usage and called the natives Indios. The term “Filipino” was reserved for the Spaniards living in the country.

There were two groups of Filipinos then. Those born in Spain but residing in the country were called peninsulares. Those born in the Philippines but with pure Spanish ancestry were called insulares. Those who were of mixed ancestry (i.e., one of the parents was not of Spanish descent) were called mestizos.

One of the early patriots to use the term “Filipino” to refer to the natives nationwide was Jose Rizal. He wrote a poem entitled “A La Juventud Filipinas” in 1878 (other writers say 1881). The revolutionaries of’ 1896 accepted the term and used it to refer to the natives who took arms against the Spaniards, whom they called Castila.

When the Americans came at the turn of the 20th century, they accepted the word Filipinas as the official name of the country but translated it into English as Philippines. They also used the term “Filipino” as the politicolegal basis of native national identity and citizenship.

Urgent Need

What is most urgently needed today is not the changing of the name of our country. It is having better knowledge of our prehistoric past. This past embodies the wisdom of our ancestors i.e., their established patterns of thought, feelings, actions, and aspirations. It represents their accumulated achievements before their overexposure to external cultures. It is the synthesis of their efforts to provide their society with a deeper and stronger foundation to stand on. Knowing these achievements will give us a new sense of identity with and pride in our heritage. It will also restore our dignity as a people.

We also need to stop criticizing our cultural traditions. The decades we have spent bashing our traditions have not been helpful. Let us stop thinking that we Filipinos are, as one historian noted, “childlike-forever curious, lacking in initiative, sensitive, and with a wrong sense of values.”

Let us remove these indictments from our textbooks. Let us put our biases aside and critically examine the events that have undermined our appreciation of our past culture . This will prepare us to better understand the reason(s) why we need to liberate ourselves from the idea that, as some earlier writers have said, “We have no cultural roots to stand on.”

Knowing our cultural history as a people is far more substantial than changing the name of our country or of our nationality. It can rekindle once more the spirit of greatness in us and imbue us with a deeper sense of moral commitment to national unity and progress. It is in this connection that prehistory becomes important to nationhood. As our national hero, Jose Rizal, had reminded us a long time ago: “Ang hindi marunong lumingon sa pinanggalingan ay hindi makararating sa paroroonan. ”

SOURCE: F. Landa Jocano, Filipino Prehistory: Rediscovering Precolonial Heritage, Punlad Research House Inc, 1998

ALSO READ: QUESTION: Was there a Kingdom of Maharlika, with a pre-colonial one true God?

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.