“Did you know that the Spanish used to chop up the babaylan and feed them to the crocodiles?” This was a statement given by someone during a discussion about the babaylan over at The Aswang Project Facebook Page. “No, I didn’t.”, was all I could really respond with. It’s a powerful narrative of persecution and suffering and I had not encountered that information anywhere before, so it immediately captured my interest. The depowering of the babaylan is without a doubt something that happened. There are documented cases of abuse, violence and murder, but the above statement took things to a whole new dastardly level. I dug around to find the introduction of this notion and then traced it back to where it may have come from.

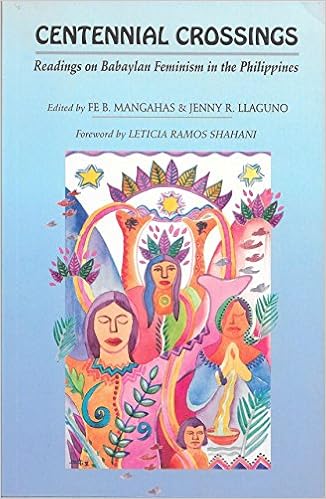

Centennial Crossings: Readings on Babaylan Feminism in the Philippines

In the 2006 book “Centennial Crossings: Readings on Babaylan Feminism in the Philippines”, there is an essay written by Leny Mendoza Strobel called “The Filipina Babaylan in the Diaspora: Encounters in Filipino American Literature” where the following is mentioned: “Historian Milagros Guerrero told me a few years ago that during the Hispanic colonial period, the babaylan women in particular were murdered and as if to make sure their bodies never return, their bodies were chopped and fed to the crocodiles.”

I reached out directly to Milagros “Mila” Guerrero asking for help in directing me to a source, story, tribe, or oral dictation that may have been heard suggesting that babaylan were “chopped up and fed to the crocodiles.” I’ve yet to receive a response. I am confident she received my message as it was forwarded directly to her by a relative as well as to her email address acquired through her publisher. I can only guess that the above quote wasn’t meant to be used as an accurate historical observation. It has not appeared in any of Guerrero’s work, but only she knows why it was said.

Back From The Crocodile’s Belly

In the Introduction for the 2015 book “Back From The Crocodile’s Belly: Philippine Babaylan Studies and the Struggle for Indigenous Memory” edited by by Lily Mendoza & Leny Mendoza Strobel the narrative evolves, although it has footing in actual historical documentation.

“A story is told that when the Spanish (who colonized the Philippines beginning in the sixteenth century) began to understand the power and potency of the babaylan, they so feared the latter’s spiritual prowess that they not only killed many of them but in some instances, fed them to crocodiles to ensure their total annihilation. While appearing in the archive primarily in connection with the 1663 babaylan uprising in Tapar, Iloilo [6], the story captures a broad truth: colonial violence did consume indigenous culture.”

Although annotated, the source material they were referencing was changed.

[6] Where the corpses of babaylan charismatic rebel leader Tapar and his followers, along with the group’s blessed holy mother, Maria Santisima, were impaled on bamboo stakes and deliberately placed on the mouth of river Laglag to be eaten by crocodiles (cf. Diaz, C. [1890] Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas, covering 1616-1694 as cited in Blair & Robertson 1998).

The translation of the Tapar revolt in Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas is seen below.

Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas

The Tapar Uprising or Panay Revolt took place in 1663 and was led by a babaylan named Tapar in Oton, Iloilo, Panay. Tapar was recently converted to Catholicism, which he syncretized into indigenous beliefs and practices.

In the visita of Malonor there was at this time a malicious Indian, a noted sorcerer and priest of the demon, who lived in concealment in the dense forest; and there he called together the Indians, telling them that he was commanded by the nonos—who are the souls of their first ancestors who came over to people these Filipinas—in whose name he assured them that the demon had appeared to them in trees and caves. This minister of Satan was named Tapar, and went about in the garb of a woman, on account of the office of babaylán and priest of the demon, with whom they supposed that he had a pact and frequent communication. Moreover, he wrought prodigies resembling the miracles, with which he kept that ignorant people deluded.

With these impostures and frauds Tapar obtained so much influence that the people followed him, revering him as a prophet, and he taught them to worship idols and offer sacrifices to Satan. Seeing that he had many followers, and that his reputation was well established, he made himself known, declaring that he was the Eternal Father; and he invented a diabolical farce, naming one of his most intimate associates for the Son, and another for the Holy Ghost, while to a shameless prostitute they gave the name of María Santisima [“Mary most holy”], as the name of Mary had been given her in baptism. Then he appointed apostles, and to others he gave titles of pope and bishops; and in frequent assemblies they committed execrable abominations, performed with frequent drinking-bouts, in which there were shocking fornications among the men and women, both married and unmarried.

Things came to a head when Tapar and his group burned down the church and murdered Spanish Friar, Francisco de Mesa by piercing him with lances in his bamboo home. Tapar and his followers fled to the mountains where they were eventually caught and killed. The following is the translation presented in the “Blair & Robertson’s The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898” which is relevant to this discussion.

“Pedro Durán proceeded, as both a soldier and a judge, to search for the aggressors; and a considerable time after the death of the venerable father, and after many endeavors, and having employed adroit spies, the Spaniards seized the principal actors in the diabolical farce. Others defended themselves and were slain; but their corpses were brought in, and carried with the criminals to the port of Iloilo. There justice was executed upon them; they were fastened to stakes in the river of Araut [60], and the body of the accursed woman who played the part of the Blessed Virgin was impaled on a stake and placed at the mouth of the river of Laglag.”

[60] The modern form of this name is Jalaur; this fine river, with its numerous affluents, waters the northeastern part of the province of Iloilo, Panay. The “river of Laglag” is evidently the Ulián, which flows into the Jalaur near Laglag (the modern Dueñas). Apparently the culprits, both living and dead, were fastened to stakes in the river, to be eaten by crocodiles.

In Conclusion

It would appear that there is certainly one historical instance where the intent was to feed a babaylan and their followers to the crocodiles. The account does not say whether this was successful or not – I would surmise it was. Still, I’d have to label the expanded narrative of the babaylan being “chopped up and fed to the crocodiles” as metaphor or speculation. While it is a persuasively gruesome image to spotlight the violence inflicted by the Spanish, there is simply no evidence to back it up. I don’t imagine that such events are beyond the realm of possibility, but I also believe that the actual documented atrocities committed by the Spanish against the babaylan are horrendous enough that we don’t need to venture into speculation.

I’ll finish this up with one final thought. In the ultimate irony, the punishment chosen for Tapar and the rebels on Panay Island, essentially venerated their deaths. As William Henry Scott sources in his book “Barangay: Sixtenth Century Philippine Culture and Society”, in the chapter on the Visayans:

“Those who died in war, who were murdered, or killed by crocodiles, traveled up the rainbow to the sky; in the Panay epic Labaw Donggon, the rainbow itself is formed by their blood falling to earth. In the sky world they became gods who, deprived of the company of their kin, were presumably ready to lend their aid to survivors who undertook to avenge their deaths.”

Jordan Clark is a Canadian born descendant of Scottish immigrants living on the homelands of the Lekwungen speaking peoples. His interest in Philippine myth and folklore began in 2004. Finding it difficult to track down resources on the topic, he founded The Aswang Project in 2006. Shortly after, he embarked on a 5 year journey, along with producing partner Cheryl Anne del Rosario, to make the 2011 feature length documentary THE ASWANG PHENOMENON – an exploration of the aswang myth and its effects on Philippine society. In 2015 he directed “The Creatures of Philippine Mythology” web-series, which features 3 folkloric beings from the Philippines – the TIKBALANG, KAPRE and BAKUNAWA. Episodes are available to watch on YouTube. Jordan recently oversaw the editing for the English language release of Ferdinand Blumentritt’s DICCIONARIO MITOLÓGICO DE FILIPINAS (Dictionary of Philippine Mythology) and is working on two more releases with fellow creators scheduled for release later this year. When his nose isn’t in a book, he spends time with his amazing Filipina wife of 20 years and their smart and wonderful teenaged daughter.