Perhaps more than any other ethnolinguistic group throughout the Philippine archipelago, the Tagalogs elicit the most confusion when the casual researcher begins to delve into the subject matter. There are several reasons for this. By the time the Spanish arrived and began making any record of the culture, the Tagalog regions were already heavily influenced by trade and migration. Populated regions were a mix of Tagalogs, Kapampangan, Tinguianes, and Muslims. The Manila area was a center for trade, which also brought migrant workers. This can explain why the Tagalog pantheon and folktales have more crossover than any other major linguistic group in the Philippines. Lastly, the Tagalog-centric “Filipino Language” push put an importance on Tagalog culture that seemed to supersede the importance of the other ethnolinguistic groups and their associated pantheons. Instead, everything is noted as being ‘Filipino’. This isn’t incorrect, but it causes confusion. I always prefer to read which exact ethnolinguistic group something belongs to, but it isn’t my place to tell others how they should share or represent their culture. Adding to the confusion was the re-writing of the Tagalog creation story to include the character names ‘Malakas & Maganda’, and F. Landa Jocano’s attempt in ‘Outline of Philippine Mythology’ to re-build the Tagalog pantheon in a palatable manner – borrowing from the Pampanga pantheon, changing names, eliminating controversial attributes, and inventing a Greek inspired family tree with demi-goddesses. This work by Jocano is solely responsible for the Ikapati/ Lakanpati controversy.

The numerous questions I receive regarding the early Tagalogs from komik creators, authors, and artists will hopefully be answered through this page. One question that is not addressed is whether the Tagalogs had a tattooing culture similar to the Pintados, Igorot, and other Austronesian neighbours. The answer is “I don’t know… maybe…probably” is the best I can answer. By the time documentation started, the practice seemed to have stopped.

Below is a compilation by Pedro A. Gagelonia of known documentation regarding the Tagalogs, presented in a manner that hopefully clears up some confusion while also creating an understandable timeline. It is by no means all encompassing, but has been annotated so you may view the source material and delve deeper into the subject. Much of this material is available to view for free on Project Gutenberg or through various PDF scans at University Libraries. These materials consist mostly of documents written from the Spanish perspective. If you are a creator, I will leave it up to you and your talents to imagine this information coming from a native perspective.

Spanish Arrival.

Clothes and Ornaments.

Religious Beliefs.

Lesser Gods.

Idols and Anitos.

Priesthood, Rituals, Sacrifices and Feasts.

Belief in the Hereafter.

Burial and Mourning Customs.

Political, Social and Economic Organization.

Ancient Laws.

System of Writing.

Marriage Customs.

Character Traits of Ancient Tagalogs.

Other Beliefs, Customs, and Tradition.

System of Waging War.

Buyo-Chewing Habit.

Pregnancy, Childbearing Practices, etc.

Omens and Auguries.

Ancient Industries.

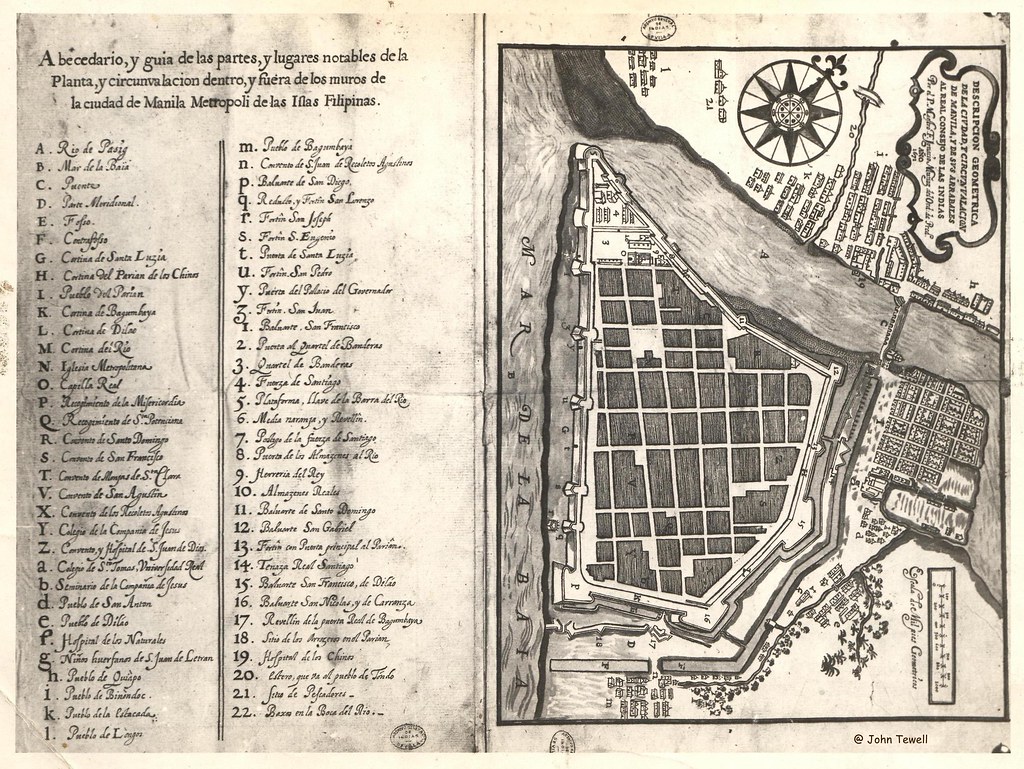

Spanish Arrival. When the Spaniards reached and occupied Manila[1] on May 20, 1571[2] they found the shores of Manila Bay settled and fortified by the Tagalogs who are referred to as Moros[3] by Spanish chroniclers. They were governed and ruled by Rajah Mura.[4] Morga notes that natives of Borneo came to the Philippines and settled in Manila and Tondo a few years before the arrival of the Spaniards. They brought with them their “wares and merchandise.” Being Moslems they preached their creed, “distributing among them their religious literature, ceremony rituals and handbooks through some crazizes* who had arrived with them, so that many of the principal men began to adopt Mohammedanism and even circumcising themselves and to assume Moorish names.”[5] The Spaniard also notes that opposite the settlement across the Pasig river was another large settlement called Tondo which was likewise ruled by another chieftain named Rajah Matanda (Lakan-Dula). These settlements “had strong buildings made of palm-trees and heavy posts, fortified with considerable number of light brass cannon or mortars and other large pieces of chamber-artillery.”[6]

“The buildings and houses of the natives,”[7] observes Morga, “in all these Philippine Islands as well as their settlements are of the same design, because they build them on the shores of the sea beside the rivers and streams or canals, the natives generally living near each other by forming barrios and villages and towns where they plant rice and raise their palm-trees, nipa plantations, orchards of bananas and other fruit-bearing trees, and where they establish their implements and devise for trapping fishes, also their navigating craft. The minority of the natives live inland, such as the Tinguians who also seek home- sites near rivers and streams, where they settle in similar fashion.

“All the houses of the natives are generally built on poles or posts high from the ground, with narrow rooms and low ceiling made of interwoven strips of wood and/or bamboo and covered with palm-leaf (nipa) roofing, each house standing by itself and not joined to any other. On the ground below, they are fenced by rods and pieces of bamboo where they raise their chickens and animals and where they pound and clean their rice. One goes up the house through stairs made of two bamboo trunks which can be pulled up. On the upper part of the house they have their open batalan or back piazza where the washing and bathing are performed. The parents and the children room together, and their house called bahandin has scant decorations and items of comfort.

“Aside from the above-described houses which belong to the ordinary people of less importance, there are those of the prominent people which are built on tree trunks and thick posts containing many rooms both sleeping and living ones, using well-elaborated, strong and large boards and trunks and containing many pieces of furniture and items of luxury and comfort and having much better appearance than those of the average people. However, they are covered by roofs of the same palm-leaves called nipa, which give much protection from the rains and the heat of the sun, and are much better than the ones with tiles and shingles even if they involve greater danger of fire.

“The lower part of the houses of natives is not used for lodging, because they use it for raising their fowl and animals, in view of the wetness and/or heat of the ground, and likewise owing to the numerous large and small rats which are destructive to the houses and country-fields. Besides, the houses are ordinarily built so that the grounds of the houses are penetrated by the waters and are thus left open to the same.”[8]

The Tagalogs under Rajah Mura resisted, as a natural reaction, the incursion of his kingdom by the Spaniards. The Tagalogs were, however, outnumbered by the combined Spanish and Cebuano troops under Martin de Goiti. To make things unpleasant for the invaders, they put to torch their homes and retreated and organized their men. In two weeks time while Legazpi and his men were busy rebuilding Manila, Soliman managed to regroup his forces and aided by his allies from the neighboring barangays or settlements engaged the Spanish naval force under the command of Martin de Goiti on June 3, 1571 at Bangkusay Channel. The battle was decisive. Soliman and about three hundred of his men were vanquished.[9]

On June 24, 1571, Legazpi proclaimed Manila as the capital of the Philippines and established the city government. Believing that he took possession of the place on Santa Potenciana’s day he also proclaimed Santa Potenciana as its patron saint.[10]

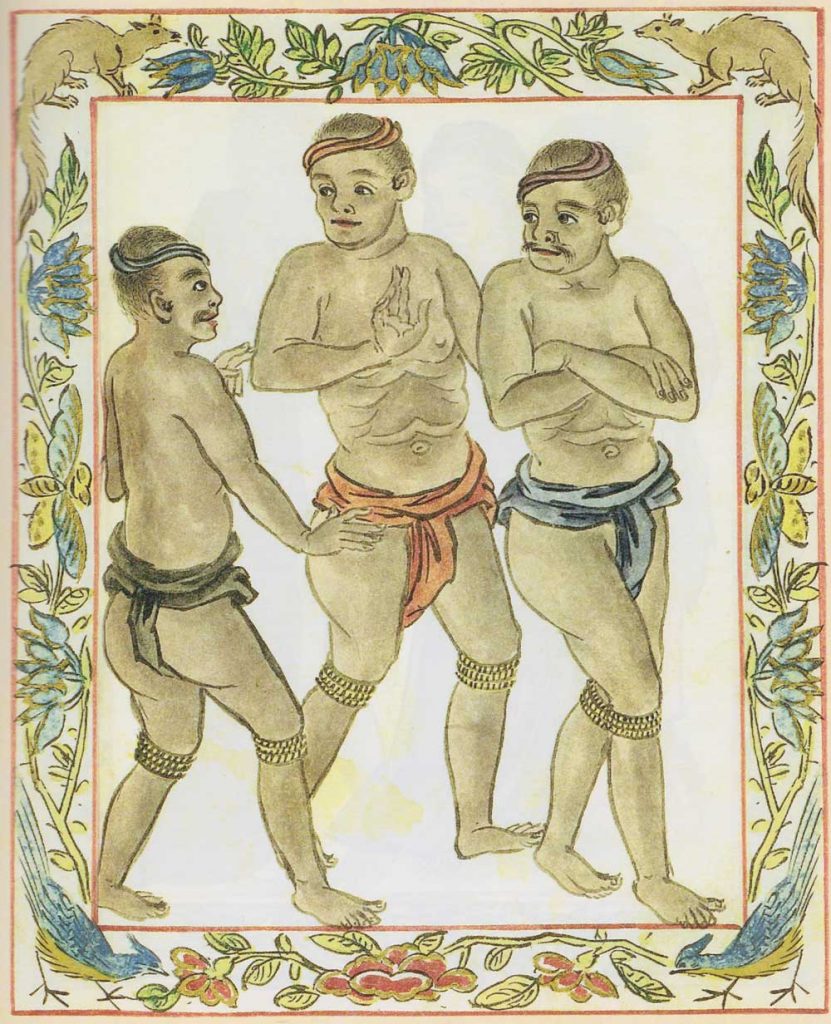

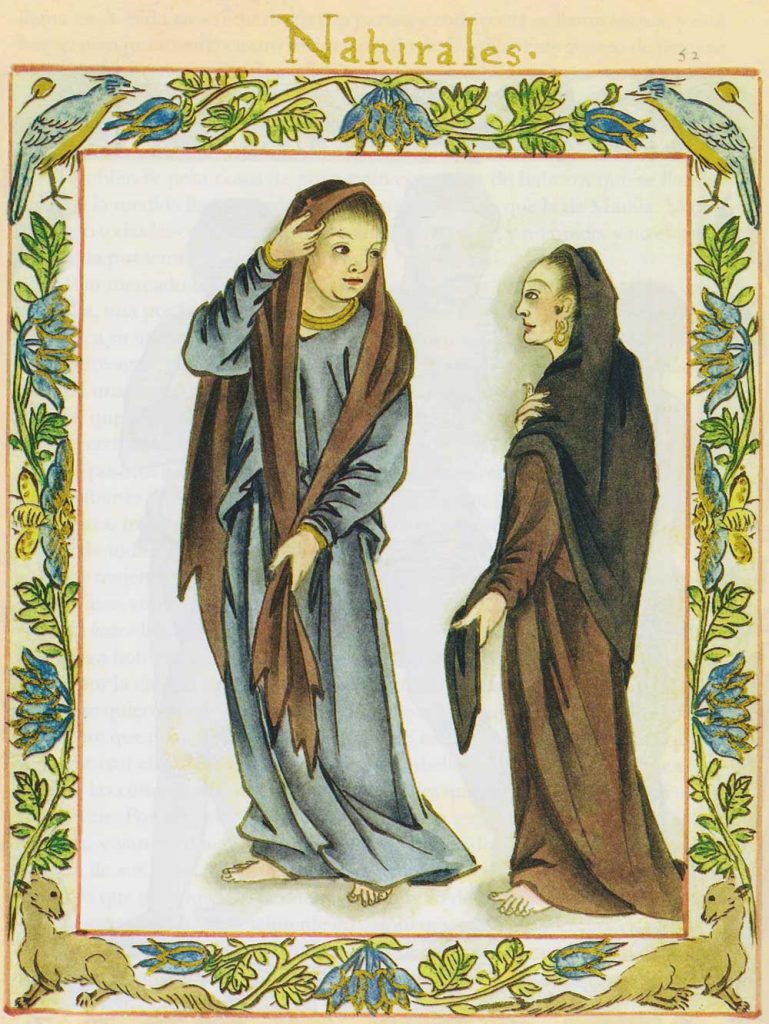

Clothes and Ornaments. “In the neighboring provinces around Manila,” writes Morga, “both by sea and by land, are natives of the island, middle-sized, of a color similar to the quince fruit, and both the men and women have good features, with very black hair, scarce beard and are quite ingenious in every way, keen, and quick-tempered, and quite resolute. They all live in the farm by manual labor, fisheries and trading sailing from one island to another, and going from one province to another by land…

“The dress which these natives of Luzon wore before the advent of the Spaniards in the land, consisted of the following: for men, clothes made by cangan fabric without collar, sewn in front with short sleeves extending down to beyond the waist, some blue and some black, while the headman used red ones which they called chininas and a colored blanket wrapped around the waist and between the legs, in order to cover their private parts. In the middle of the waist they wore the bahaque, the legs being bare and the feet also bare, the head uncovered, with a narrow kerchief tied around it tightly over the forehead and temples, called potong. Around the neck they wore a long chain of engraved gold links the same as we wear it, some links being larger than the others. On their arms they wore thick and engraved gold bracelets called colombigas made in different designs. Some men used strings of stones, red agate and of other colors and blue or white stones, which to them are valuable. As garters, they used on their legs some strings of these stones and some strings painted black and tied around their legs, several times.

“In a certain province named Zambales, they shave their heads closely from the middle to the forehead, with a large lock of loose hair on the back of the head. The women throughout this province wear sayas or dresses with sleeves called varo, of the same cloth or of different color, without any chemise except white cotton sheets wound around the waist falling down to their feet. Others use colored ones around their bodies as shawls, with much gracefulness. The principal women use scarlet or silk one or other fabrics, interwoven with gold thread adorned with fringes and other ornament. They use many gold necklaces around their necks, bracelets around their wrist and heavy earrings made of engraved gold, and rings of gold and stone on their fingers. Their black hair is gracefully tied with a ribbon or knot to the head. After the Spaniards came to the land many men ceased to wear gee- strings, and instead they wore balloon-trousers made out of the same blankets and cloths, also hats on their heads. The headmen wear dresses decorated with pounded gold-braid of various workmanship, and many of them wear shoes. Likewise, the principal women were curiously shod and many of them wear velvet shoes with gold trimmings, also sheets as undershirts.”[11]

A comparative description of the Tagalogs and the Bisayans found in Quirino and Garcia’s translation of the Boxer Codex is as follows:[12]

“They have no king among them nor persons deputized to administer justice, nor personages for government—in this, they are the same as the Bisayans; the chiefs do as they please, removing and giving lands they wish for little reason, although it is true that the Moros* are more amenable to reason and are more orderly and harmonious in their affairs and in their way of life (than the Bisayans) and have the advantage in all reasonable matters. They have better houses and buildings, more orderly, although located in swampy land or along river banks. The Moros are dressed with cotton clothes and are not naked like the Bisayans. Their clothes consist of (words not understood) and without collars; and with their sleeves and their (words not understood) they come dressed, although they wear below the waist some mantle well located, which covers the flesh up to the knees, because below that their legs protrude. From the calf to the knees they wear many chainlets often made of brass which they call bitiques; these are worn only by the men who regard them as very stylish. They also wear many golden chains around the neck, specially if they are chiefs, because these are what they value most, and there are some who wear more than ten or twelve of these chains. They wear a head-dress of small cloth which is neither wide nor long and which they wrap once around the head with a knot. They do not have long hair because they cut it as in Spain. They are not accustomed to wearing a beard, nor allowing it to grow although in general they are all hairy; what grows is carefully removed; and the Bisayans do likewise. The Moros wear only mustaches which they do not remove and allow to grow all they can. The Bisayans in no manner are accustomed to wear any shoes nor do the men wear ear holes as do the Bisayans: the women carry much gold jewelry because they are richer than the Bisayans. Men and women also wear many bracelets and chains of gold in the arms. They are not used to wearing them on the legs. Women likewise wear around the neck golden chains that men do. The Moros do not paint any part of their body. There is some difference in language, although everybody understand each other, because they are like Castilian and Portuguese and even more similar. They are very fond of trading, selling and bargaining with each other; thus they are great merchants and very cunning in their dealings. They are very fond of making money and try every way of earning it.”

Religious Beliefs. The Tagalogs believe in one Supreme God. “Like all primitive religions, that of the Tagalog was,” says Father Horacio De La Costa, “closely interwoven with their culture and traditions. It governed not only ritual and sacrifice, feast and festival, but almost the entire life of the individual and the community. It covered household tasks, planting and harvesting, traveling and hunting, war and love with a network of prescription and tabus. It was the burden of song and story; indeed, it was by stories heard in childhood, songs pounded on the festive board, chants beating time to the oar that it was chiefly transmitted. This, rather than any reasoned conviction, was the source of its strength and vitality. In a primitive culture religion touches everything; there is nothing completely profane. The Tagalogs conceived his universe. Behind it all was a figure dimly discerned in origin, the maker of heaven and earth: Bat-hala Meikapal, Bat-hala The Fashioner. But little was known about this beneficent being; only fitful glimpses of him came through the hosts of jealous and exigent. Anito filled the foreground of the spirit world.”[13]

The Moros[14] of the Philippines have the belief that the earth, the sky and everything therein were created and made by only one God, which they call in their tongue Bachtala napal nauca calgna salabat,[15] which means God the creator and preserver of all things. They call him by the other name of Mulayri.[16] They say this is their God in the atmosphere before there was sky or earth or other things, that it was eternal, and not made nor created by anybody; that he alone made and created everything we have, said solely on his own will, to make something as beautiful as the sky and the land, and that he did it, created from the earth a man and a woman from whom all men and generations in the world have descended.[17]

“They say further that when their ancestors had news of this god which they have as for their highest, it was through some male prophets whose names they no longer know, because as they neither have writings nor those to teach them,[18] they have forgotten the very names of these prophets, aside from what they know of them who in their tongue are called tagapagbasa nan sultan a dios; which means readers of the writings of god; from whom they have learned about this god, saying what are already told about the creation of the world, people, and about the rest. This they adore and worship and in certain meetings held in their homes—because they have no temples for this purpose nor are used to it—they have feasts where they eat and drink splendidly; in the presence of some persons whom they call in their tongue catalonas who are like priests.”[19]

Antonio de Morga is quite emphatic in his observation when he points out that “in matters of religion, they (natives) proceeded in primitive fashion and with more blindness than in other matters, for the reason that, aside from being Gentiles, without any knowledge of the true God, they did not take pains to reason out how to find Him, neither did they envision a particular one at all…There were those who worshipped a certain bird with yellow color which lives in the mountains, called Batala …”[20]

Taking to task the observations of other chroniclers, Morga notes the following: “‘Blue bird,’ says the Jesuits Chirino and Colin who in their capacity as missionaries ought to be better informed, ‘of the size of a thrush that they called Tigmamanukin they assigned to him the name Bathala. Well now; we don’t know any blue bird either of this size or of this name. There is a yellow bird, though not completely so, and it is kuliawan or golden oriole. Probably this bird never existed and if it existed at one time, it must have been like the eagle of Jupiter, the peacock of Juno, the dove of Venus, the different animals of Egyptian mythology, that is, symbols which the populace and the ignorant laymen confuse with the divinities. This bird, blue or yellow, would be the symbol of God the Creator whom they called Bathala May Kapal, in the words of the historians, that is why they would call him Bathala, and the missionaries who had little interest in understanding things in which they did not believe and which they despised, would confuse everything as an Igorot or a Negrito would do should he or she worshipped the image of the Holy Ghost or the symbols of the Apostles represented at times only by a bull, an eagle, or a lion, and would relate in the mountain among the laughter of his friends that the Christians worshipped, a dove, a bull, a sparrow hawk, or a dog as those symbols appear represented many times’”[21]

Lesser Gods. The Tagalogs apparently have other gods “whom they say serve them for some other particular things.”[22] First in the Boxer Codex list is Lacanbaco,[23] the god of fruits of the earth; second, was Oinon sana, god of the fields and mountain; third, Lacapati. an idol with both male and female attributes “to whom they make the sacrifices of food and words, asking him for water for their fields and for him to give them fish when they go fishing in the sea, saying if they do not do this they would not have water for their fields and much less would they have any fish when they go fishing;”[24] fourth, Hayc, god of the sea; and fifth, the Moon whom they “adore and revere whenever it is new, asking it life and riches because they believe and they have it for certain it can do so completely and lengthen their life.”[25]

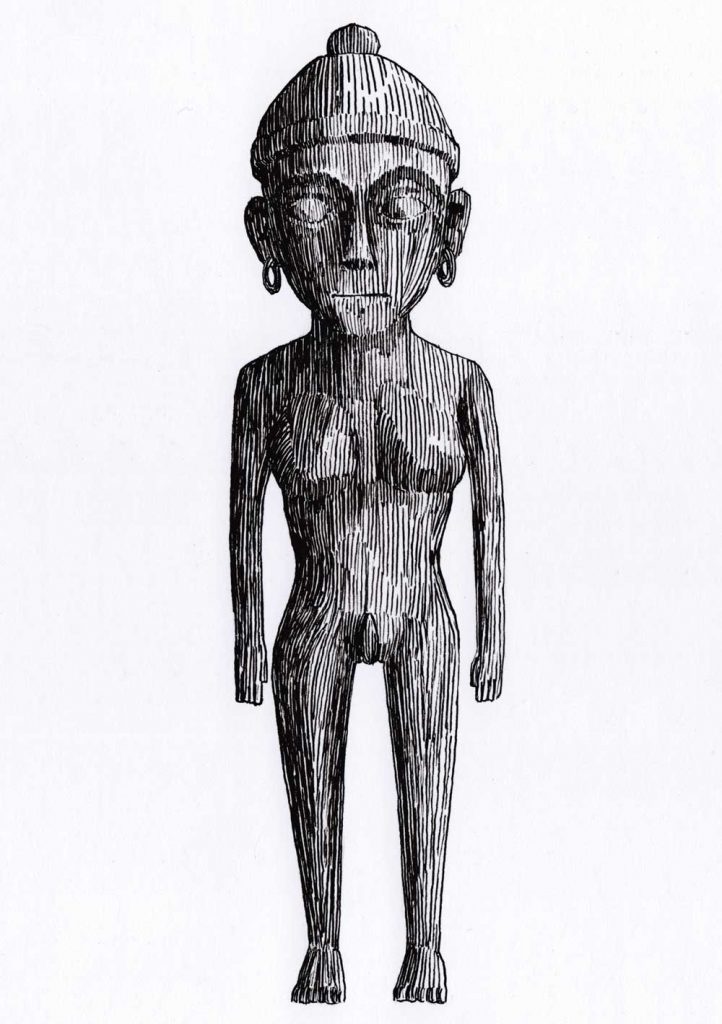

Idols and Anitos. Aside from the lesser gods or deities Bathala appears to have special deputies “whom he sent to the world to produce, in behalf of men what is yielded here.”[26] These are the anitos, and each anito has a particular office whose blessings and favor they implore when they go to the battlefield, anitos to shield them from diseases as well as “anitos for house, whose favor they implored whenever an infant was born, and when it was suckled and the breast offered to it.”[27]

Another anito whom Fr. Juan de Placensia, O.S.F. identifies as Dian Masalanta is known to be the “patron of lovers and generations.”[28] Even the departed relatives are deified and believed to assume spiritual powers, e.g., “they are in the air always looking over them and that illness they have given or removed by their grandparents…”[29]

Chirino says that “it was a general practice for anyone who could successfully do so to attribute divinity to his old father when the latter died.” [30]

To perpetuate their ancestors’ memory they keep “idols of stone, wood, gold, or ivory called licha or laravan.”[31] Fr. San Agustin after the lapse of a hundred years says that “they make their ancestors offerings of food according to their custom; and what has been preached to them and printed books avail but little, for the word of any old man regarded as a sage has more weight with them than the word of the whole world.”[32]

A stone figure made of “adobe” or tuffa, discovered in Palatpat, Calatagan, Batangas, is presumed to be pre- Spanish and of the late 14th or early 15th century. A stone carving of similar style which is now at the National Museum has also been found in Taal, Batangas, probably of the same date having a height of 25.5 cm.

Priesthood, Rituals, Sacrifices and Feasts. Speaking of what Fr. Colin calls priests[33] in the ancient Tagalog society, Morga makes the following remarks: “There were no temples or houses[34] of common worship of idols anywhere in the Islands, and each one performed in his own house, whatever worship of his anitos he pleased, without any particular ceremony or solemnity, neither was there any priest or man of religion who should attend to religious matters except some old men or women Catalonas (pythonesses), great sorcerers and wizards who deceived the people and communicated to them whatever they wished, and according to their needs, and answered to them questions with a thousand and one lies and absurdities. They rendered prayers and offered ceremonies to the idols in behalf of their sick people; they believed in omens and superstitions which the devil inspired them to do, so that they could tell whether their sick persons would live or die. They made treatments and cures and other sortileges to ascertain the future or any event through various ways. And God permitted apparently that the people of these Islands be prepared with the least possible assistance, to receive the preaching of the Gospel so that they might know the truth with more ease, and so that there would be less effort exerted to take them away from darkness and error in which the devil held them in bondage for many years. They never practised human sacrifice like people in other kingdoms. They believed that there was a further life beyond where those who had been brave and had performed daring deeds were rewarded and where those who had done evil would be punished accordingly, but they were, however, at a loss to determine where these things would happen or the why and wherefore of them.”[35]

The derogatory and contemptible remarks against the Catalonas by the Spanish chroniclers are because the missionaries found them to be the stumbling block in their missions. As a matter of fact “the converts as a rule,” says Fr. H. De La Costa, S.J., “found little difficulty in abandoning their pagan beliefs and practices… Only the Katalonan, the men and women shamans of the old religion caused the missionaries some concern.”[36]

The people were required to surrender their idols to the missionaries to be destroyed. “Wooden idols were simply burned,” says Fr. De La Costa. “A big bonfire of them and of the furniture used in their workshop was made at Antipolo in 1598.”[37] The following is a letter which Fr. De la Costa quotes in his book. “As I was writing this,” Almerici says in a letter to a friend in Rome in 1597, “they brought me four or six little gold idols to be broken up.”[38]

Rituals are always associated with feasts where part of the offering is eaten. “Of these there are men or women whom they say do so; that is, say certain prayers or secret words, with some food or liquid offering, asking for the well being of he who makes that sacrifice; at the same time throwing some kind of bones or lots, to which they are also accustomed; and for this purpose the catalonas or priests are given certain payments for doing the sacrifice.”[39]

“They usually eat pigs, chickens and the best dish and dressed food made in their own way. Parents and neighbors join and sing and dance to the tune of drums and bells and the beating of palms and cries. They build altars with (illegible) adorned by the best mantles and golden ornaments they have (illegible). They offer everything to the anito, whom they call by that name. They invoke the maguan, smearing certain parts of their body with the blood of what had died, believing that it would give them health and long life. All of this is administered by a priest dressed in female garb. They call him bayog or bayoguin; another woman for the same office they call catalonan. This feast terminates when everybody or most of them gets drunk; this is called maganito by the Indians. What the maganito is has already been said. Let us tell about the priests and priestesses they have, and what is attached to their office and consecutively later the rites and ceremonies in particular affairs that the Indians have and use.

“Although these Indians have no temples, they have priests and priestesses who are the principal persons of their ceremonies, rites and omens, and to whom all the important affairs are entrusted, paying them well for their labor. Ordinarily they dress as women, act like prudes and are so effeminate that one who does not know them would believe they are women. Almost all are important for the reproductive act, and thus they marry other males and sleep with them as man and wife and have carnal knowledge. Finally, these (words not understood). These are called bayog or bayoguin. The priestesses are usually old and their function is to cure the sick with superstitious words, or assist in drinking feast by invoking the spirits of their ancestors for their purpose and conducting the ceremonies which we shall see. The function of the priests is to help in all occasions; in general, to help the priestesses invoke the spirits, although with more pomp, ceremony and authority. There are also other kinds of the latter who are called catalonan whose function is proper to the priestesses, and neither these nor the priestesses have such authority as those dressed in women’s clothes. Finally, neither one nor the other are witches, and when they perform witchcraft or deceits it is for the purpose of emptying the pockets of the ignorant people.

“When sick they use many kinds of rites, some with more paraphernalia and others less, depending on the quality of each, because principal persons ordinarily hold maganitos or drinking feasts in the manner we have said, assisted by one or more priest who invokes his anitos which, they say, come and which those present hear as a noise like that of the flute which the priests say is that of the anito who speaks and says that the sick person would have health: the feast thereupon proceeds with great merriment. And if the sick man dies, after the anito had said he would get well, the priest gives as an excuse that the intention of his anito was good but that other anitos more powerful intervened. There are those who light a sheaf of grass and throw it out of the window, saying that by doing so the bad anitos responsible for the malady would be scared into leaving. Others cast lots by tying a string to their hand, a piece of wood, or the tooth of a crocodile, and manipulating it themselves, saying that the cause of the malady of one is so-and-so or is not so-and-so, and since the omens are manipulated by them as they please, it is evident that they can foretell whatever they please or what is certain. Some who are not so well-to-do offer a little cooked rice and a bit of fish and wine, requesting of the anito for health; others offer a moderate drinking feast to the anito in which assist a priest of the sick, whom they call catalonan, who administers what is needed and then says the cause of the illness is that the soul has left the body and until it returns the sick would not recover. Later the sick asks him to order the return (of his soul) and for this they pay him in advance according to agreement. Later the catalonan goes to a corner alone talking to himself and after a while returns to the sick and tells the latter to be happy because his soul is already back in the body and he would get well; with this they hold a drinking feast, and if the sick would die, they never lack excuses to absolve themselves. In these drinking feasts they heat water with which to wash the faces of all present, the healthy and the sick, saying that it prevents sickness and lengthens life.”[40]

Besides the Katalonan the ancient Tagalogs had a number of other priests more or less identified by the kind of work they perform. Fr. Plasencia gives the following classification: first, the katalonan; second, the mangagauay “those who pretend to cure or heal the sick but in truth are themselves the ones that induce the sickness by their charms;” third, manyisalat, those with the “power of applying such remedies to lovers that they would abandon and despise their own wives, and in fact could prevent them from having intercourse with the latter”; fourth, mancocolam, “those who have the ability to emit fire from himself (themselves) at night, once or oftener each month,”; fifth, hocloban, a witch believed to be “of greater efficacy than the mangagauay, without the use of medicine, and by simply saluting or raising the hand, they kill them whom they chose”; sixth, silagan, a liver-eater; seventh, magtatanggal, those who show themselves at night to many people without, their heads or entrails; eighth, asuang, a witch that is supposedly found in the Visayan Islands; ninth, mangagayoma, those capable of making charms for lovers out of herbs, stones, and wood, capable of infusing the heart with love; tenth, Sonat, a preacher whose duty is to “help or die, at which time he predicted the salvation or condemnation of the soul”; eleventh, Pangatahojan, a soothsayer, capable of predicting the future and twelfth, Bayoguin, a man whose predilection is women.[41]

Belief in the Hereafter. The ancient Tagalog forebears believe that “there was a further life beyond where those who had been brave and had performed daring deeds were rewarded and where those who had done evil would be punished accordingly,” to which Morga comments thus: “but they were however at a loss to determine where these things would happen or the why and wherefore of them.”[42]

A similar observation is recorded in the Boxer Codex.[43] “They have always known, and have knowledge that they have a soul, which on leaving the body goes to a certain place that some call casan and others maca. They say this is divided into two large towns; an arm is in the middle of the sea, which some say is for the soul of mariners who are dressed in white; and the other is for the rest who are dressed in red for greater attraction. They say that the souls who inhabit these places die seven times, and some others are resuscitated and undergo the same travail and miseries that they undergo in their bodies in this world; but they have the power to remove and give health, which they effect through the air; and for this reason they revere and ask them for help by holding drinking feasts.”

Fr. Chirino has a unique observation and says that “a woman whether married or single, would not be saved who did not have some lover. They said that man in the other world, hastened to offer the woman his hand at the passage of a very perilous stream which had no other bridge than a very narrow beam, which must be traversed to reach the repose that they call calualhatian.”[44]

Another equally interesting account is given by Fr. Plasencia. “These infidels said that they knew that there was another life of rest,” he says, “which they called maca, as if we should say ‘paradise’ or in other words ‘village of rest.’ They say that those who go to this place are the just, and the valiant, and those who lived without doing harm, or who possessed other moral virtues. They said also that in the other life and mortality, there was a place of punishment, grief, and affliction, called casanaan, which was ‘a place of anguish,’ they also maintained that no one would go to heaven, where there dwelt only Bathala, ‘the maker of all things,’ who governed from above. There were also other pagans who confessed more clearly to a hell, which they called, as I have said, casanaan, they said that all the wicked went to that place and there dwelt the demons, whom they call sitan.”[45]

The Jesuit Colin surmises that the souls of those “who perished by the sword, who were devoured by crocodiles, as well as those killed by lightning go to the blest abode by means of the rainbow called by them balangao.”[46]

BACK TO TOP

Burial and Mourning Customs. Respect and reverence for the dead members of the ancient Tagalog family is sufficiently and rightfully noted by the early Spaniards. “They buried their dead in their own house,” writes the learned Morga, “keeping their bodies and bones for a long time in boxes, and venerating their skulls as if they were living in their presence.[47] In their funeral rites, neither pomp nor processions played any part, except only those performed by the household of the deceased; and after grieving for the deceased, they indulged in eating and drinking to the degree of intoxication among themselves, the relatives and friends.”[48]

Colin’s observation offers a more detailed account as follows: “To the sound of mournful music,” he says, “they washed the body, perfumed it with the gum of the storaxtree or benzoin and other tree gums that are found in all these mountains. After this they shrouded the body, wrapping it up in more or less cloth in accordance with the rank of the dead. The more important ones they anointed and embalmed, in the style of the Hebrews, with aromatic liquors, which preserved the bodies from putrefaction, particularly the one done with aloes that they called ‘Eagle’ wood, very acceptable and much used in all this India outside of the Ganges. They also used for this the sap of the leaf of the buyo… They put a quantity of this sap through the mouth so that it would go inside the body. The grave of the poor was a hole in the ground of his own house. The rich and the powerful, after holding them for three days mourning, were placed in a box or coffin of indestructible wood, decorated with rich jewels and with a covering of thin sheets of gold on the mouth and eyes. The coffin was of a single piece…and the cover was so well adjusted that no air would get in. And because of this carefulness, at the end of many years, numerous bodies were found intact. These coffins were placed in one of three places in accordance with the wishes and order of the deceased—in the house, among the jewels, or below it, above the ground, or on the ground itself, in an open hole and fenced around with railings, without covering the coffin with earth. Beside it they usually place another box containing the best clothes of the deceased and from time to time they placed several dishes containing food. Beside the men they placed his weapons and beside the women their looms or other tools they had used.”[49]

Taking issue on the observations made by Morga and Colin who manifest contempt for the Tagalog’s belief that “if the aged died a natural death they were sure of going to Heaven with divine attributes,” Rizal says: “We see nothing censurable in this contrary to the Jesuit’s opinion. This filial piety of venerating the memory of his progenitors is less reprehensible than the monastic fanaticism of making saints of their confreres, availing themselves of the most ridiculous inventions and grasping so to speak, even at the boards, like that of Bishop Aduarte, etc., etc. ‘And the old men themselves died with these pride and fraud, making appear at the time of their sickness and death a seriousness and crisis that to them seemed divine!’ Between this tranquility, sweet solace that was offered by that religion at the last moments of life, and the anguish, fear, and terrifying and cheerless sense that monastic fanaticism infused in the mind of the dying, the mind free from every preoccupation can judge. If the lofty judgment of God is not unknown to us; if the Omnipotent has given us life for our ruin, why embitter the last hours of life, why torture and discourage a brother, precisely at the most terrible moment of his life and on the threshold of eternity? It will be said: so that he may mend and reform. It is not the means, nor the occasion, nor is there time left.

“In this connection, ‘…that primitive religion of the ancient Filipinos was more in conformity with the doctrine of Christ and of the first Christians than the religion of the friars. Christ came to the world to teach the doctrine of love and hope that may console the poor in his misery, that may lift up the downcast and may serve as a balm for all the sorrows of life.’”[50]

Jar burial is mentioned in the Boxer Codex, the practice of which has been proved by the location and excavation of jar burial sites not only around the Manila area but also in the different parts of the country.[51]

“Generally in these islands the dead,” the Boxer Codex reads, “are buried without delay, although not all are given the same pomp because the people are (words not understood). They do no more than cover the deceased with a white sheet and bury the body next to their house or field. Later they hold a drinking feast and with this conclude the (ceremony). But the chiefs are covered with the richest silken sheets they have and placed in an incorruptible wooden coffin in which some gold is placed in accordance with the rank of the deceased, and bury him under a house which they have built for the purpose, where all the dead relatives are interred, and enclose the grave with curtains and place a lighted lamp over the grave and food as offerings for the dead, depending on the importance of the deceased; sometimes a man or woman is placed on guard all the time even after three or four years have passed. In some places they kill slaves and bury them with their masters in order to serve them in the after life; this practice is carried out to the extent that many load a ship with more than sixty slaves, fill it up with food and drink, place the dead on board, and the entire vessel including the live slaves are buried in the earth. They hold offerings by drinking for more than a month. Others keep the corpse in the he use for seven days so that the fluids may flow, and in the interim with all that fetid smell they are drinking without halting. Later, they remove the flesh from the bones and throw it to the sea; the bones are then placed in an earthen jar. After a considerable time if they deem fit they bury the jar with all or if not they leave it in their house. But the most repugnant and horrible thing they do is when, interring the bones, they drink with the bones serving as cups; and this is what they call batan to mariveles.

“There are others who do not bury their dead, but take them to a hill and there hurl them out and then they flee hurriedly because they believe that he who is last (to leave) will die, and for this reason there are few who dare carry them: those who take the risk do so because they pay them well for it. When burying the dead they do not pass it through the main door but through a window, and if they do so, close it later and change it to another part (of the house) because they believe that those who pass where the dead has passed would also die. They cry over the dead not only in the house but on the road to the burial place, proclaiming the deeds and virtues of the deceased in a manner more like singing than crying because of the way they wail and raise the voice without tears. In this they purposely obtain the aid of persons who know how to do so and almost are professionals. When a chief dies nobody in that town sings or plays any kind of musical instrument in celebration, not even those who pass aboard ships, under pain of punishment.”

During the period of mourning,[52] “the widow or widower, and the orphans and other relatives who felt most keenly their grief, expressed their sorrow by fasting, abstaining from eating meat, fish and other viands.” For the duration of mourning which lasted up to the time of burial, they were allowed to eat vegetables and fruits but in limited quantities.

“Among the Tagalogs,” writes Fr. Chirino, “the color for mourning is black… Upon the death of a chief, silence must be observed in the village during the period of mourning, until according to his rank; and during that time no sound of a blow, or otherwise might be heard in any house under penalty of some misfortune. In order to secure this quiet, the villages on the coast placed a sign on the banks of the river, giving notice that no one might travel on that stream, or enter or leave it, under penalty of death—which they forcibly inflicted, with the utmost cruelty, upon whomsoever should break the silence. Those who died in war were extolled in their dirges, and in the obsequies which were celebrated the sacrifices made to or for them lasted for a long time, accompanied by much feasting and intoxication. If the deceased had met death by violence, whether in war or in peace, by treachery, or in some other way, the mourning habits were not removed, or interdict lifted, until the sons, brothers, or relatives had killed many others—not only by the enemies and murderers, but also other persons, strangers, whoever they might be, who were not their friends. As robbers and pirates, they scoured the land and sea, going to haunt man and killing all whom they could, until they had satiated their fury. When this was done, they made a great feast for invited guests, raised for interdict, and in due time abandoned their mourning.”[53]

Political, Social and Economic Organization. The ancient Tagalog politico-socio-economic set up is patterned and defined along the economic standpoint.

The political unit is called a barangay,[54] ruled by the datu or lakan. Fr. Colin calls the barangay chieftain maginoo whom he contrasts with the Visayan datu.[55] Each barangay consists of several families “acknowledging a common origin.”[56] The datus not only administer the needs of their own barangays but also settle their disputes according to the customs and traditions handed down from their elders and ancestors.

They also lead their men in time of war. Miguel de Loarca notes the following:

“They had chiefs in their respective districts, whom the people obeyed; they punished criminals and laid down laws that must be observed… They greatly esteem an ancient lineage, which is therefore a great advantage to him who desires to be lord.”[57]

Morga’s observation vividly portrays the extent of the authority exercised by the principalia. “The authority which these principal men or leaders that they considered its components as their subjects, to treat well or mistreat, disposing of their persons, children and possessions at their will and pleasure without any opposition from the latter, nor duty on their part to account for the principal’s action, (sic) Upon their committing any slight offense or fault, these henchmen were either punished, made slaves or killed. It has happened that for having walked in front of lady principals while these were having their ablutions in the river; for having looked at them with scant respect; or for other similar reasons, these henchmen have been made permanent slaves.”[58]

Equal to the datus in everything except authority are the maharlikas or nobles who are “bound to their lord by kinship and personal fealty, owing him aid in war and counsel in peace, but in all else free, possessing land and chattels of their own.”[59] The rights of the datus and of the nobility are also acknowledged by the women. Although the right of chieftainship is inherited, such can also be attained through one’s merit, by means of one’s resourcefulness, cunning and brute strength. “For even though one may be of low extraction,” observes Fr. Colin, “if he is seen to be careful, and if he gains some wealth by industry and schemes…whether by farming and stock-raising, or by trading; or any of the trades among them, such as smith, jeweler, or carpenter…in that way he gains authority and reputation, and increases it the more he practises tyranny and violence …”[60]

Next in line in the social structure is the timaua[61] who does not have the tint of the “noble blood of the maharlika” but are, like them, free. To this group belong the free-born persons and emancipated slaves.[62]

The rest are the alipin, more specifically known as the aliping namamahay and the alipinq saguiguilid.[63] The former are allowed to own their houses and personal property but are bound to the datu to till his land. They go with their master wherever the latter goes. Besides rendering services to their master for which they received no remuneration they also have “to give their master an annual tribute consisting of one hundred gantas of unhusked rice, which ganta had more than a fourth of an almud[64] and of all the seeds plant. They give their chief a little of everything: if they make quilan[65] they gave him a jar; if they go hunting for deer, they give him a leg; and if their master is a follower of Mahomet and they reach the deer before the dogs kill it, they bleed it with a spear, because that is what the Mohammedan priests have ordered—not to eat the flesh unless it had first been bled.”[66]

Fr. De la Costa opines that the aliping saguiguilir or aliping saguiguilid are “household dependents, chattel slaves, captured in war or reduced to bondage according to Malay custom for failing to pay their debt.”[67]

As described in the Boxer Codex, the saguiguilir “stays and lives in the house of his master, serves on him day and night, and is fed by him. The master can sell these slaves who live in their houses; none of them is married, all being single; and if a male desires to get married, he is not taken away from the chief, and in this case upon marriage is called namamahe who lives by himself. Slaves who live in the house of the chiefs surprisingly are allowed to get married and the males are not disturbed in any way. Slaves who live by themselves have the obligation to equip the ship of their master when he goes out, carry his food, and when their chief holds an obligatory drinking feast, such as when he marries or someone in his family dies or if he is inundated or is made a prisoner or if he becomes sick. On all these occasions big feasts are held, and the slave who lives by himself has to bring a jar of wine, so much rice, and to assist in such feasts. If the chief has no house, these slaves construct one for him at their expense. The master only holds a drinking feast when the posts are cut, another when these are raised, in which all the Indians of the town come to help to lift them. And if some Indian should fall in doing so, they consider it as a bad omen, and cease construction. They hold another feast when the roof is placed, at which all the slaves of the chief attend and cut the wood and do everything needed for the building of the house. For all these, they are given nothing more than food. When some of these slaves die, they have these duties: if they have children, the chief would take one to serve him at his house and these are the aguiguiltil who live within the house of the chief; and if a free Indian marries a slave woman, or a slave with a free woman, the children are divided in this manner: the first born is free, the next is enslaved, and this order is kept in dividing as well with the mother as with the father; and of the enslaved children, the chief cannot take more than one in his house; and this is proper only if the father and the mother are slaves. If there be many children, when more are taken for service in the house of the master, they hold this as a grievance and a tyranny, and when leaving the house of the chief to get married, they never return to serve him, except to render the duties of those of the namamahe; unless the chief forces them to do so, which they consider as a great tyranny and offense inasmuch as they have been given license to leave their house and then made to return thereto. These customs the slaves have inherited from their predecessors.

“An Indian was also made a slave although a freeman when they found him stealing, no matter how small it may be if he was poor and had no one to give him money as penalty; if such an Indian had rich relatives to pay for him, he would become the slave of such relatives; this his relatives do in order not to see him be a slave of others. Likewise if one was found with the wife of another man and was not killed or did not have enough properties to pay the penalty, he was made a slave. If some poor Indian asked for a loan and payment was not made within a certain time, he had to do so at interest as time elapsed; thus the interest accrued. This matter of interest is used up to now when making money loans. I say that with anything they loaned within a given time, two had to be paid back, and after another period without payment four had to be returned; and in this manner the debt would go on increasing until they, became slaves. There are many such slaves: because of the debts of the parents the children are taken and made slaves. When some orphan remains without anybody to turn to, the chiefs would enslave him on the excuse that his grandfather owed them something even though it was not so. If the orphan had neither father nor mother, nor uncle or other relative to support him he had to serve the chief as if a slave who had been bought.”[68]

Speaking of the saguigilires and namamahay slaves Morga writes that they “are full-time, half-time and part-time or one-fourth-part slaves. And it happens that if one of the parents of a child was free and the child was the only one, then he was a half-time slave, being only one- half free. If they had more the first child followed the station of the father being either bond or free, the second child follows the status of the mother, and if there is an uneven numbered child, the latter was half-slave and half free. The children of these mixed parents, i.e., bond and free, became a free father or mother and of a half-slave. These half or fourth-part slaves, whether saguiguilid or namamahay ones, serve their masters alternately, that is, for one moon, and are free the next moon, and so on. according to the rules of slavery.

“The same thing happens with regard to partitions among the heirs: a slave may serve many masters, each one on his own time. When a slave is not entirely so but only half or one-fourth part slave, he is entitled in view of his part-free status, to compel his master to compensate him at a just rate, for his used part-time freedom from service, which price is based on the persons according to the standing of the saguiguilid or namamahay slave whether half or fourth-part slave. However, in the case of a regular full-time slave, the master cannot be compelled to exempt him or compensate him at any price.

“Among the natives the ordinary price for a saguiguilid slave is usually not over ten taels of good gold worth eighty pesos each, and only half of this amount if he is a namamahay slave and the rest at a proportionate price according to the person, and his age.

“There is no definite origin or source of this system of slave among the natives, because they all belong to these Islands and are not foreigners. It is believed that this matter started with the controversies and wars between themselves, and it seems certain that those who could do so, took this opportunity for whatever slight differences or reasons there might be, and reduced the vanquished to slavery. Likewise, slavery also resulted from debt and usurious loan-contracts between the natives, the amount of which increased with time owing to failure to settle them and to misfortune, the debtors them becoming slaves. Thus, all this system of slavery can be traced to unsavory and unjust causes, among them the suits between the natives, which have engaged the attention of the Courts of Justice and confessors, and the human conscience.

“These slaves constitute the greatest possessions and wealth of the natives of these Islands, for the reason that they are very useful and necessary to them in their work and activities. They are-sold, traded and made the object of contracts, like any other commodity, among themselves, in the common markets of the towns, provinces and of the Islands. Thus, in order to avoid innumerable lawsuits that would ensue if these cases of slavery would be brought to Court, and their origin and beginning inquired into, the system and the slaves are now preserved in the same condition in which they existed heretofore.”[69]

Ancient Laws. The ancient laws of the Tagalogs consist mainly of traditions and customs. These are observed faithfully and religiously, particularly respect for parents and elders which are observed with great exactitude “…not even the name of one’s father could pass the lips, in the same way as the Hebrews (regarded) the name of God. The individuals, even the children must follow the general (custom).”[70]

Determination of both civil and criminal cases is the obligation of the chief and the elders of his barangay. In settling cases they summon both parties and endeavor to have them come to some form of understanding and agreement.[71] Should they fail to come to an understanding “then an oath[72] was administered to each one, to the effect that he would abide by what was determined and done. Then they call for witnesses, and examined summarily. If the proof was equal (on both sides), the difference was split; but if it were unequal, the sentence was given in favor of the one who conquered. If the one who was defeated resisted, the judge made himself a party to the cause, and all of them at once attacked with the armed hand the one defeated, and execution to the required amount was levied upon him. The judge received the large share of this amount and some was paid to the witnesses of the one who won the suit while the poor litigant received the least.”[73]

In criminal cases the rank of the parties involved affects the course of action that was to be taken. If the chief was murdered all his kinsmen hunt the murderer and his relatives and both sides engage in war until mediators settle the quantity of gold for the murder in accordance with their custom. Death penalty is only imposed when the murderer and his victims are common men and can not afford to pay any indemnity.

The solution of theft cases is simplified by requiring all the suspects to undergo some form of a test based on the assumption that God protects the innocent. The most common tests are: 1st, the river ordeal—the suspects are required to plunge with wooden spear into the river. He who comes out first is regarded the criminal; 2nd, the boiling water ordeal—the suspects are required one after the other to take out a stone from a vessel with boiling water; he who refuses to put his hand into the water is adjudged guilty; 3rd, the candle test—the suspects are given candles of the same sizes and lighted at the same time and the holder of the candle that loses its light first is the culprit.[74]

“In matters of inheritance,” Morga continues “all legitimate children inherited equally all the property which the parents had acquired. However if there was any personal or real property left by the parents, in the absence of legitimate and by the asawa, they were inherited by the nearest relatives from the collateral branches of the main family tree. This was effected either by will or testament or, in its absence, by custom. No solemnity was required in the making of a will aside from simply leaving it in written form, or by stating the wish verbally in the presence of well-known persons.

“If any principal or nobleman was a chief of a barangay or clan, he was succeeded in the office or dignity, by his eldest son had by his asawa or married wife, and in his default, by the second son had by her. In the absence of male children, by his daughters in the same order. In the absence of legitimate children, the succession reverted to the nearest of kin belonging to the same lineage and family of the principal who last possessed it.

“In the event that any native having female slaves should have had intercourse with any of them and come to have children as a result thereof, her child as well as herself became free thereby, but if she failed to have any, she remained a slave.

“The child of slave-mothers and those had by another man’s wife, were considered children of ill-repute, and they did not succeed like the legitimate heirs to the estate, neither were their parents bound to bequeath any property to them; and even if they were children of dignity or nobility or to the privileges of their fathers, and only remained in their station and were considered ordinary timawa plebeians like the rest of them.

“The contracts and negotiations with the natives were generally considered illegal, so that each of them had to take care of himself or see how he could best attend to his business.

“Loans made for profit were very common, and they bore excessive interest, thus doubling or increasing the more their settlement was being delayed, until the creditors would take everything their debtors had, together with their persons and their children, if they had any, in the capacity of slaves.

“The offenses were punished upon complaint of the aggrieved parties. Thefts were particularly punished with severity by making slaves out of the thieves, and sometimes sentencing them to death, likewise, oral defamations and insults particularly those uttered against the principals. There was a list of many things and words considered extremely insulting and discrediting when uttered against men or women, which were excused with more difficulty than offenses committed against persons, or injuries against their bodies.”[75]

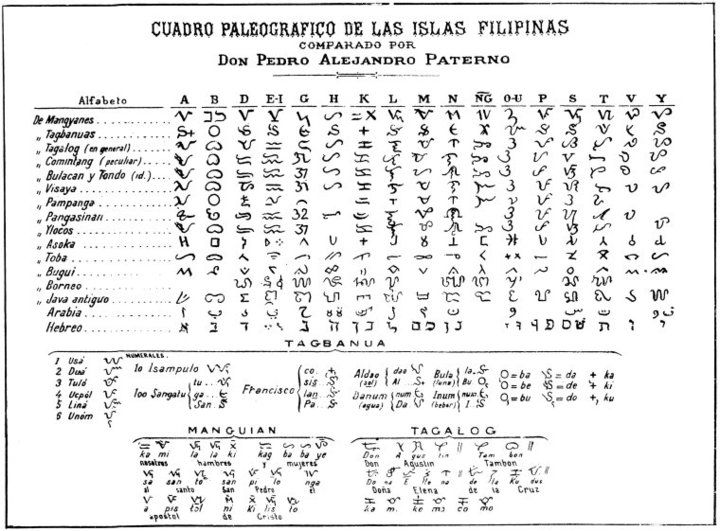

System of Writing. The ancient Tagalogs as well as the Ilokanos, Bisayans, Pampangos, Moslems, and other ethnic groups have their own system of writing. Before the advent of the Spaniards they have long been able to read and write. Fr. Marcilla is quoted by the late Justice Ignacio Villamor as having given his opinion as follows: “That the Tagalogs had their own alphabet is a thing beyond doubt; and though it is true that up to the present time no document, slabs, inscriptions or other objects pertaining to the natives have been discovered to show the existence of their alphabet, the assertion of the first and oldest historians of the country is so clear and positive that to deny it would be preposterous.”[76]

The Tagalogs “count the year by moons and from one harvest to another. They have certain characters that serve them as letters with which they write what they want,” the Boxer Codex reports. “They are very different looking from the rest that we know up to now. Women commonly know how to write with them and when they write they do so on the bark of certain pieces of bamboo, of which there are in the islands. In using these pieces which are four fingers wide, they do not write with ink but with some stylus that breaks the surface and bark of the bamboo to write the letters. They have neither books nor histories, and they do not write at length except missives and notes to one another. For this purpose they have letters which total only seventeen. Each letter is a syllable and with certain points placed to one side or the other of a letter, or above or below, they compose words and write and say with these whatever they wish. It is very easy to learn this and any person can do so in two months of studying. They are not so quick in writing, because they do it very slowly. The same thing is in reading; which is like when school children do their spelling.”[77]

“The people of Manila Province called Tagalogs,” writes Morga, “have a rich and abundant language whereby all that one desires to say can be expressed in varied ways and with elegance, and it is not difficult to learn and to speak the same.

“Throughout the Islands, writing is well developed through certain characters or signs resembling the Greek or Arabic, numbering fifteen signs in all, three of which are vowels which serve in lieu of our five vowels. The consonants are twelve. With these and certain points or signs and commas, everything one desires to say can be expressed and spoken fully and easily, just like with our own Spanish alphabet.

“Writing was done on bamboo pieces or on paper, the line beginning from the right to the left as in the Arabic writing. Almost all the natives, both men and women, know how to write in this dialect, and there are few who do not write it well and properly.

“This language of the province of Manila is understood as far down as the entire province of Camarines and other islands adjoining Luzon, where they do not differ very much from each other, except that in some provinces the language is spoken with greater purity than in others.”[78]

Fr. Colin notes that “without doubt the most courteous, grave, artistic, and elegant is the Tagalog for it shares in four qualities of the four greatest languages in the world, namely, Hebrew, Greek, Latin and Spanish…The polish and courtesy, especially of the Tagalogs and those near them, in speech and writing are the same as those of very civilized nations. They never say ‘tu’ (i.e. ‘thou’) or speak in the second person, singular or plural, but always in the third person: (thus), ‘The chief would like this or that.’ Especially a woman when addressing a man though they be equal and of the middle class, never say less than ‘Sir’ or ‘master’ and that after every word: ‘When I was coming, sir, up the river, I saw sir, etc.’ In writing they make constant use of very fine and delicate expressions of regard, and beauties and courtesy.”[79]

“All these islanders,” writes Fr. Chirino, “are much given to reading and writing, and there is hardly a man, and much less a woman, who does not read and write in the letters used in the island of Manila—which are entirely different from those of China, Japan, and India…By means of these characters they easily make themselves understood and convey their ideas marvelously, he who reads supplying, with much skill and facility, the consonants which are lacking. From it they have adopted the habit of writing from left to right. Formerly they wrote from top to the bottom, placing the first line on the left (if I remember right), and continuing the rest at the right, contrary to the custom of the Chinese and Japanese—who although they write from top to bottom, begin from the right and continue the page to the left.[80]

“They used to write on reeds and palm leaves using as a pen an iron point; now they write their own letters, as well as ours, with a sharpened quill, and, as we do, on paper. They have learned our language and its pronunciation, and write it even better than we do, for they are so clever that they learn anything with the greatest ease. I have had letters written by themselves in very handsome and fluent style.” [81]

Justice Villamor observes that the direction of the old Filipino writing has been a moot to historians. “The old and modern writers have not been able to agree upon this point,” he says. “While some maintain that the Filipinos wrote from top to bottom, placing the lines of the writing from left to right, others maintain that they wrote horizontally from left to right, the lines following each other from top to bottom as we do now.”[82]

Among the Spanish chroniclers who believe that the early Filipinos wrote from top to bottom are Fathers Sta. Ynes, Delgado and Chirino. Fathers Colin and Ezguerra and Marche differ in opinion, however. Antonio de Morga and Fathers Buzeta and Bravo opine that ancient Tagalogs wrote from right to left. Sinibaldo de Mas claims the opposite.

An eminent Filipino scholar, Trinidad Pardo de Tavera, remarks: “The language in which the alphabets resemble those of the Filipinos are written horizontally from left to right, a direction common in writing all the alphabets of Hindu origin.”[83]

Rizal in his notes to Morga’s Historical Events of the Philippine Islands, says: “With respect to the direction of the writing of the Filipinos there are some very contradictory opinions. It must be noted that the writers who have taken up the subject in these recent times, excepting Marche believe it to be horizontal. Jamboulo, however, who seems to have seen this writing centuries before Christ, agrees with Chirino who says: ‘They wrote from the top to the bottom (x r w o e r x n t w)’ Colin, Ezguerra, and Marche believe in the opposite direction, from the bottom to the top. The horizontal direction was adopted after the coming of the Spaniards as Colin attests, the direction that Pardo de Tavera supposes and which Mas believes to be the only one by the piece of manuscript he reproduced, subsequent to the coming of Legazpi which could induce him to err like the others and also our Morga.

“What can be deduced it seems is that they wrote in two ways, vertical and horizontal: Vertical in the first epoch when they wrote on canes and palm leaves because in that way the writing was much easier, and horizontal when the use of paper became general. As to the rest, the form of the characters lends itself to these different directions.”[84]

Certain self-styled scholars today ridicule the idea of considering the Philippine system of writing as alphabets and strictly qualify the system as mere scripts. Be that as it may, we are prone to qualify the scripts as alphabets.

The tables from Gardner’s Philippine Indic Studies reveal the extent and depth of the diffusion of culture among the peoples from the earliest time to the present.

Marriage Customs. What Tagalog forebears practised before the advent of the Spaniards in the islands are still practised by some of thecountrymen today especially those in the remote areas. It is a practice to marry only their kind. “Marriages among the natives,” writes Morga, “are generally between the principal and their fellow principals or nobles. Likewise timauas marry among those of their own station, and the regular slaves also marry their fellow slaves, but sometimes they intermarry among different castes.[85] The natives have one wife each with whom a man may wed and she is called inasawa[86], but behind her are other women as friends.”[87]

Marriage during the early days is more or less a matter between parents of the bride and the groom.[88] The interested parties after agreeing on all the terms of the union of their children execute some form of an agreement called talingbohol. This is usually formalized by giving the future bride and groom some jewel. As soon as the groom’s parents are ready with the dowry a habilin is made. Actually this is a sign that the dowry has been paid for just “like the sign in shops to show that the price was fixed and that the articles could not be sold at another price.”[89]

All relatives and friends of the bride and groom assemble at the bride’s home three days before the wedding. They assemble there to make the palapala which is a sort of a bower. This is done in order to make the house larger to accommodate all expected guests. The celebrations which usually last for three days mean “days of expense, of racket, of reveling, of dancing and singing …All the relatives and friends who go to weddings are also wont to take each some little present. These gifts were set down very carefully and accurately, in an account, noting whatever each one gave. For if Pedro so and so gave two reals at this wedding, two reals were also given to him if he had another wedding in his house. All this money is spent, either in paying, if anything is due for the wedding, or as an aid in the expenses. Or if the parents of both the young couple are niggardly, they divide it and keep it. If they are generous, they use it in the pamamahay, or furnishing of the house of the couple… The nearest relatives give a couple a jewel as a mark of affection, but do not give money. These jewels belong to the bride and to no one else.”[90]

“The groom,” notes Morga, “was the one who contributed a dowry, given by his parents, while the bride did not bring anything to the marriage community until she inherited in her own right from her parents. The solemnization of marriage consisted in the mutual agreement between the parents and kinsmen of the contracting parties, the paying of the concerted dowry of the father of the bride, and in the gathering of all the relatives in the house of the bride’s parents for the purpose of celebrating with eating and drinking the whole day until sunset. At night the groom carried the bride to his home where she remained in his care and protection. The spouses could separate and dissolve their marriage ties owing to trivial causes and upon proper hearing had before the relatives of both parties and some elders who participate therein, and who rendered judgment, upon which the dowry received was returned to the husband, and it was called bigaycaya as a voluntary offering, except in cases where the separation was caused by said husband’s fault, when it was retained by the parents of the wife to keep.”[91]

Fr. Juan de Plasencia’s account about the practice of the Tagalogs is very noteworthy. “In the matter of marriage dowries,” he says, “which fathers bestow upon their sons when they are about to be married, and half of which is given immediately even when they are only children, there is a great deal more complexity. There is a fine stipulated in the contract, that he who violates it shall pay a certain sum which varies according to the practice of the village and the affluence of the individual. The fine was heaviest if, upon the death of the parents, the son or daughter should be unwilling to marry because it had been arranged by his or her parents. In this case the dowry which the parents had received was returned and nothing more. But if the parents were living, they paid the fine, because it was assumed that it had been their design to separate the children.”[92]

The dowry called bigaycaya is set according to the rank of the contracting parties. If by chance the parents of the bride ask for “more than the ordinary sum,” the bride’s parents are under moral obligation to give the married couple a gift or token: for example, a “gold jewel” or “a bit of clear land.” This is called pasonoc. Another amount which is part of the dowry is the panhimuyat which is the amount for the mother of the bride to compensate her rearing and educating the daughter. Another part of the bigaycaya is called pasoso which is the sum paid to the chichiva or nurse who reared the bride.[93]

The marriage is solemnized in an unorthodox manner. “On solemnizing the marriage,” reports the Boxer Codex, “they unite the pair, making them eat from the same plate, and while eating—or when they are united for this purpose—their parents arrive and wish them many years of life and love for each other. At night, either her mother or some old woman bring the couple to bed where they are made to lie down and are covered with a sheet, as indecent jests are uttered; then the rest go down the house and to the right of the bed of the couple nail a stake, saying that the husband does it to show he is not impotent for copulation. This matter of the stake is not done everywhere, but only in some places. It is likewise customary for the man to give a larger dowry by paying something to each of the nearest relatives of the woman, which is a bribe for them to consent to the marriage; without this and without dowry they very rarely marry, because women consider it as a big insult even though they may be of the worst and wretched kind.”[94]

Marriage with their relatives is permitted except with brothers.[95] In love making they also use incantations. They use herbs to attract the attention of those whom they love just as they do to people they abhor. Some also use a magic script to ward off suspicion of their real intentions.[96]

Divorce. Divorce is resorted to in case of adultery. No physical punishment is exacted. Instead, the guilty spouse pays the aggrieved party such indemnity as the elders consider to be proper, provided that both parties shall forgive and forget the whole incident.[97]

“If the cause of the divorce is unjust, the man parts from his wife, he loses the dowry; if it is she who leaves him, she must restore the dowry to him. But if the man has just cause for divorce, and leaves her, his dowry must be restored to him; if in such case the wife leaves him, she retains the dowry…In case of divorce, the children are divided equally between the two; without distinction of sex; thus if they are two in number, one falls to the mother and one to the father; and in a state of slavery the same thing occurs when husband and wife belong to different masters. If two persons own one slave, the same division is made; for half belong to each, and his services belong to both alike. These same modes of marriage and divorce are in use among those who marry two or three wives. The man is not obliged to marry them all in one day; and, even after having one wife for many years, he may take another, … as he can support.”[98]

Fray Plasencia notes that “in case of a divorce before the birth of children, if the wife left the husband for the purpose of marrying another, all her dowry and an equal additional amount fell to the husband; but if she left him, and did not marry another, the dowry was returned. When the husband left his wife, he lost half of the dowry, and the other half was returned to him. If he possessed children at the time of his divorce, the whole dowry and fine went to the children, and was held for them by their grandparents or other responsible relatives.”[99]

Character Traits of Ancient Tagalogs. The Spanish chroniclers have conflicting opinions about the women. Fray San Agustin notes that “the women are very devout, and in every way of good habits. The cause for this is that they are kept so subject and so closely occupied; for they do not lift their hands from their work, since in many of the villages they support their husbands and sons; while the latter are busied in nothing else but in walking, in gambling, and wearing fine clothes, while the greatest vanity of the women is in the adornment and demeanor of these gentlemen, for they themselves are poorly and modestly clad…”[100]

“For they are of better morals, are docile and affable, and show great love to their husbands and to those who are not their husbands. They are really very modest in their actions and conversation, to such a degree that they have a very great horror of obscene words; and if weak craves acts, their natural modesty abhors words.”[101]

Fray San Agustin’s observations are confirmed by Sinibaldo de Mas. “There is no doubt that modesty is a peculiar feature in these women,” he says. “From the prudent and even humble manner in which the single youths approach their sweethearts, one can see that these young ladies hold their lovers within strict bounds and cause themselves to be treated by them with the greatest respect. I have not seen looseness and imprudence, even among prostitutes. Many of the girls feign resistance, and desire to be conquered by a brave arm. This is the way, they say, among the beautiful sex in Filipinos. In Manila no women makes the least sign or even calls out to a man on the street, or from the windows, as happens in Europe; and this does not result from fear of the police, for there is complete freedom in this point, as in many others. But in the midst of this delicacy of intercourse there are very few Filipino girls who do not relent to their gallants and to their presents. It appears that there are very few young women who marry as virgins and very many have had children before marriage. No great importance is attached to these slips, however much the curas endeavor to make them do so. Some curas have assured me that not only do the girls not consider it dishonorable, but think, on the contrary, that they can prove by this means that they have had lovers. If this is so, then we shall have another proof that these Filipinos preserve not a little of their character and primitive customs; since according to the account of Father Juan Francisco de San Antonio, it was a shame for any woman, whether married or single, before the arrival of the Spaniards, not to have a lover, although it was the same time a settled thing that no one would give her affection freely.”[102]

In a similar vein, Colin makes the following observation; “In writing they make constant use of very fine and delicate expression of regard and beauties and courtesy. Their manner of salutation when they meet one another is the removal of the potong, which is a cloth like a crown, worn as we wear the hat. When an inferior addressed one of higher rank, the courtesy used by him was to incline his body low, and then lift one or both hands to the face, touch the cheeks with them, and at the same time raise one of the feet in the air by doubling the knee, and then seating oneself. The method of doing it is fixed firmly, and double both knees without touching the ground, keeping the body upright and the face raised. They bend in this manner with the head uncovered and the potong thrown over the left shoulder like a towel; they have to wait until they are questioned, for it would be bad breeding to say anything until a question is asked.” [103]